A decade ago, I lived in a bachelor apartment next to a prison in Kingston, Ontario. The only thing between my building and the red-topped turrets of Collins Bay Institution was a stretch of prison farmland. Thinking back on it now, I remember seeing the cows who once grazed there, though at the time I hardly noticed them.

There was something else that escaped my notice at the time: the Harper government’s sudden and secretive decision in 2009 to shut down all the prison farms in Canada. Now, the Liberal government is considering reinstating them. There is an opportunity here for more than a reboot. It’s time for a whole new beginning.

Prison labour through the ages

Prison labour was a touchstone of colonial rule, not least in the settlement of Canada.

“The only correctional program that has existed from the earliest days of prisons was work,” notes Graham Stewart, former executive director of the John Howard Society. “Because work was also seen as a punitive thing. It was ‘make people work.’ And it literally meant breaking rocks or turning a crank. Completely mindless, and used, in fact, as torture.”

Gradually, prison farms evolved to be a means of feeding prisoners, though the treatment of prisoners remained harshly punitive until the Great Depression of the 1930s. Mounting poverty and crime rates compounded prison tensions with overcrowding, leading to a series of riots that drew public attention to problems in penal philosophy and management style.

The result was a four-year investigation into Canada’s prison system, culminating in the Archambault Report of 1938, which recommended a new model “to encompass interesting creative activities through programs designed to modify the core behaviours, attitudes and habits of inmates.”

This marked a critical shift from repressive methods of punishment to those emphasizing rehabilitation and reintegration, strategies intended to reduce recidivism.

In 1980, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) launched CORCAN to provide rehabilitative programming through vocational training, which included prison farms, focusing on the development of generic skills (problem solving, communication, teamwork) applicable to all forms of employment. A 1995 review found that CORCAN participants were less likely to return to custody upon release, compared to the national average.

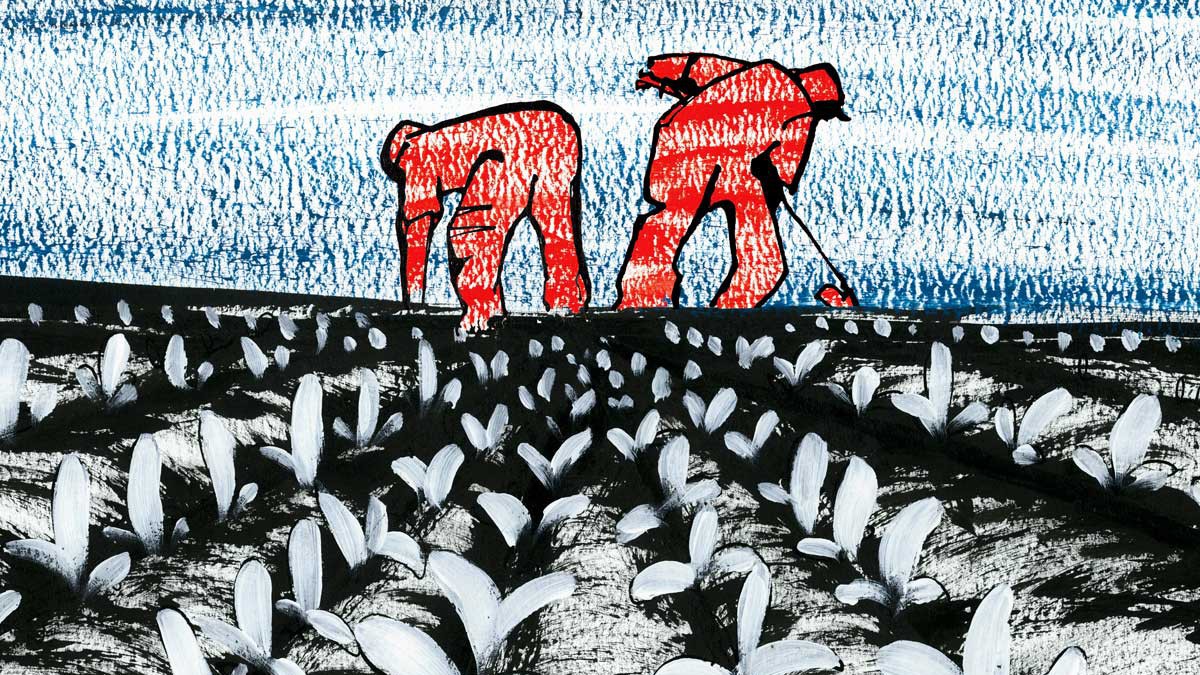

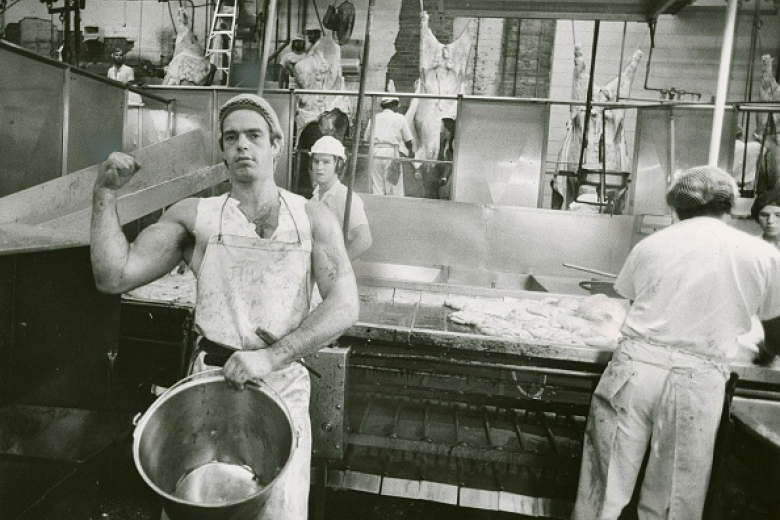

By the turn of the 21st century, prison farms were at the peak of their popular appeal for their contribution to rehabilitation and local food security. On the 900-acre Frontenac Institution farm at Collins Bay Institution, prisoners were offered employment (paid a maximum of $6.90 per day) to collect, process, and package some 4,000 litres of milk and 700 eggs daily from 160 cows and 10,000 hens for distribution to 15 prisons in Ontario and Quebec. Prisoners also worked in construction, mechanical maintenance, welding, and clerical work. The direct effect on recidivism was not specifically tracked, yet paroled farm workers had the lowest rate of parole suspension.

The political environment changed after the 2001 terror attacks in New York and Washington. In 2003, the century-old office of the Solicitor General – responsible for prisons, police, and parole – was replaced by Public Safety Canada, ushering in tighter security measures under a single entity responsible for public safety and emergency preparedness. In 2006, Stephen Harper’s Conservatives were elected to a minority government with a clear “tough on crime” agenda.

Immediately, the government ushered in reforms that were concerned with the rights of victims over the rights of criminals. Harsher sentences, widespread cost-cutting, and reduced access to programming effectively divorced the concepts of rehabilitation and public safety that had formerly been wed under the Archambault Report.

Canada’s prison farms shuttered between 2009 and 2011

- Frontenac Institution (Kingston, ON)

- Pittsburgh Institution (Kingston, ON)

- Westmorland Institution (Dorchester, NB)

- Rockwood Institution (Winnipeg, MB)

- Riverbend Institution (Prince Albert, SK)

- Bowden Institution (Innisfail, AB)

In 2008, the Conservatives initiated a strategic review of CSC programming, which led to the decision to phase out Canada’s six federally funded prison farms.

The question at the time – and to this day – is: why?

Though the findings of the strategic review were never made public, two reasons for closing the prison farms were cited by the government: the farm program cost $4 million per year ($11 million in expenses, $7 million in sales) and it didn’t teach employable skills. Despite intense public and political scrutiny, the government never wavered from this two-pronged defence, though then-Public Safety Minister Peter Van Loan added that the farms “are not viable as rehabilitation, either.”

“We don’t look for profit from other prison programs,” noted then-Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers. “We’ve never had a discussion about substance abuse programs or anger management programs needing to be profitable. We see them as an investment into people’s rehabilitation and possible reintegration. Prison farms should be thought of the same way.”

As for employable skills, the farm at Frontenac Institution has been replaced by a laundry facility. Prisoners push buttons. Even the folding is automated.

To this day, the real reasons behind the decision to shut down Canada’s prison farms remain a mystery. One speculation is that Harper considered the farms “soft” on prisoners, and that the move was made as part of a wider “business transformation” of corrections, including the clustering of institutions into multi-level security facilities (“super prisons”) signalling the Americanization – and possible privatization – of the Canadian prison system. As the farms were being shut down to save $4 million (0.0015 per cent of CSC’s $2.6 billion budget), the government went on a multi-billion-dollar spending spree, described by Sapers as “the single largest expansion of federal correctional system capacity in [Canada’s] history.” Thousands of new cells and several new prisons were built to accommodate an anticipated increase in prison population as a result of “tough on crime” legislation.

It is conceivable that the Conservatives thought that their decision to close the farms would pass unnoticed. Certainly, they could not have anticipated the resistance it would spark.

“It was a bitter afternoon,” recalls former production supervisor Ron Amey of the day it ended. Amey oversaw the Frontenac farm for four years before retiring, partly on principle, after it was shut down. “Nobody in the government ever told us ‘You guys did a great job.’ Basically, we got a phone call saying the farms are closed, too bad, so sad, start working on dismantling it.”

It wasn’t just the loss of the farms that outraged prison communities and the communities surrounding them. It was the way in which it was done: the hollow excuses and suspicions behind it, the shroud of secrecy enveloping it, the reversal of ideology and social values implicated in it, and the total dismissal of a clear democratic voice opposing it.

Nowhere was this democratic voice louder than in Kingston, the “penitentiary capital of Canada,” with six prisons operating in the region.

The grassroots coalition Save Our Prison Farms (SOPF) emerged in the wake of the closure announcement, rallying individuals across the political spectrum who opposed the move. As described by SOPF organizer and food activist Andrew McCann: “The future of food, the future of justice, and the future of democracy converge on this issue of the prison farms, so profoundly, really.”

In August 2010, the SOPF campaign culminated in a two-day blockade at the Frontenac Institution to prevent removal of the “Pen Farm Herd” cows. Hundreds of protesters peacefully blocked the entrance to the prison while animal transport trucks idled behind a mounting police presence. The blockade crumbled by the end of the second day, with 24 people arrested for “attempted criminal mischief.”

As a last resort, SOPF formed a co-operative to purchase a portion of the Pen Farm Herd at auction. Today, the herd consists of about 32 mostly second- or third-generation cows who remain in the care of local farmers in anticipation of the farm’s return. SOPF has committed to continue their campaign “’til the cows come home,” as reflected in the title of Lenny Epstein’s documentary film about the efforts.

Advocates would have to wait until 2015, when the Conservatives were defeated by Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, before any prospect of restoring the prison farms would emerge. By the summer of 2016, Liberals had launched a public consultation process and feasibility study into reopening the prison farms, with an initial focus on the two Kingston sites.

In August 2016, over 300 community members gathered at Kingston City Hall for a town hall meeting hosted by MP Mark Gerretsen and Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Ralph Goodale to discuss reopening the Kingston farms.

Former inmate Pat Kincaid, who had spent 35 years in prison and his final four years on the Frontenac farm, testified that the cows had completely reversed his trajectory of recidivism. On the farm, Kincaid discovered responsibility, tenderness, the value of hard work, and perhaps most importantly for him, “how to ask for help.” “Because of the cows,” he said, “you have been safe from me for seven years.”

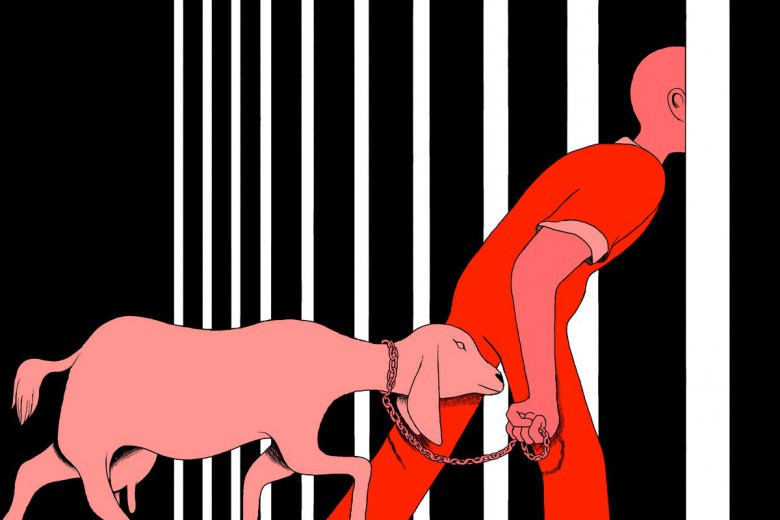

Although support for prison farms is widespread, it is not unanimous. In 2010, a group of prison abolitionists came together in Kingston to form the advocacy group EPIC (End the Prison Industrial Complex), later publishing a collection of essays titled “Reap What You Sow: Radicals Reflect on Kingston’s ‘Save Our Prison Farms’ Campaign.” One abolitionist, writing under the pseudonym Auroch, in an essay titled “Fire to the Prisons Means Fire to the Prison Farms,” compared the treatment of prisoners with that of the cows: “Through years of controlled breeding this herd was prized for its docility and productivity. In many ways, cattle are easy to uphold as model prisoners.”

“The logic of animal husbandry dovetails with the logic of incarceration. […] Through confinement, coercion, and other more readily recognized forms of violence they are molded [sic] over time with the goal of creating a docile, controllable mass who have their lives stripped from them in order to create value.”

Animals on and off the prison farm

My mother, Franceen Neufeld, and I work for the Suffering Eyes Project, which supports farmed animal sanctuaries across North America. When we heard that the Pen Farm Herd might be returned to prison dairy production, my mother commented to me in passing, “Wouldn’t it be nice if the cows could come back to a prison sanctuary?”

Dairy operations, even in the best of circumstances, necessitate forced impregnation, the separation of mothers from their newborns, the slaughtering of most male calves, and the early slaughtering of cows after their milk productivity declines (usually at 4-6 years of age, versus a natural lifespan of 20 years). A sanctuary, which suggests the permanent, non-exploitative care of animals, does not require prisoners to continually form and break bonds of affection and trust. This simple ideological shift would propel us further along the long arc of our historical trajectory away from exploitation, toward rehabilitation and, ultimately, healing.

Auroch, the abolitionist contributor to the EPIC zine, argues that prison sanctuary is “a reformist aim,” but concedes that this model is a step toward undermining a carceral mentality.

In August 2016, my mother and I introduced a sanctuary proposal at the town hall meeting, and afterwards launched the Save the Herd petition, which gained nearly 4,000 signatures by the time it was submitted to the government in January 2017.

We then helped to launch Evolve Our Prison Farms (EOPF), a coalition of community partners who share SOPF goals of restoring the farms and returning the Pen Farm Herd, only in the form of plant-based agriculture enhanced by sanctuary.

Under this model, the cows would contribute natural fertilizers to an integrated farming system while presenting a unique opportunity for humane education. On the old prison farms, prime agricultural land was used to grow crops to feed large numbers of cows, who were then “converted” into milk and meat – an inefficient use of land and resources. An acre of land can produce up to 15 times more vegetable protein than animal protein. And while the dairy industry workforce has been largely automated, the organic plant food sector is increasing dramatically and is more labour intensive.

In short, the EOPF model would produce more food of higher nutritional quality at a fraction of the capital investment and operational costs of dairy, while offering rehabilitative programming and meaningful training in rapidly developing green economies.

A growing number of SOPF supporters have expressed that they would be satisfied with sanctuary as an outcome for the herd, and none have opposed it. The EOPF proposal has led McCann, among others, to “a serious rethink.” He admits that “a pivot toward animal rights may be an important part of becoming a sustainable species ourselves, in this ecological century.”

A decision on the future of prison farms is anticipated in 2017. While the government may be tempted to seek after what’s been lost, favouring the old familiar model, the EOPF coalition is committed to continuing its campaign until the cows come home to sanctuary.