In June of 2018, the federal Liberals announced that “the cows are coming home”: closed nine years earlier by the Harper government, the prison farms at Joyceville and Collins Bay institutions in southern Ontario, just outside of Kingston, would be opening again.

For many in Kingston, it seemed like a victory. Since February of 2009, when the Tories first announced the sudden closure of all six federal prison farms in the country, a coalition of local farmers, residents, and community advocates called Save Our Prison Farms (SOPF) had been holding public meetings, organizing, and even getting arrested trying to keep the farms from closing, and then fighting to have them reopened.

Organic farmer Dianne Dowling, member of the National Farmers Union (NFU) and former president of the Kingston local, was one of those spearheading the effort. “The prison farms represent about 1,500 acres of some of the best farmland in the area,” says Dowling. “Our [union] local had been working to build the local food and farm system in the area for several years, through events and projects, and we did not want such good farmland going out of farming.” The campaign grew and began attracting national attention, and when cows from the original herd were being auctioned off in 2010, more than 100 groups and individuals contributed money to form the Pen Farm Herd Co-op, which was able to purchase some of the cows and keep the bloodline going in the hopes of one day restoring the herd from its original stock.

The winds began to shift with the election of the Trudeau Liberals in 2015 and, in 2016, a public meeting in Kingston marked the beginning of a community consultation process about reopening the farms. Seven members of the public, including members of SOPF, were asked to join a citizen advisory panel to address the issue, and Dowling was one of them. She describes the panel’s relationship with the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) and its business arm, CORCAN, as “respectful,” but notes that the panel’s role is strictly advisory. Still, thanks to the work of SOPF and the Pen Farm Herd Co-op, in June of this year some of the descendants of that original herd were delivered to Collins Bay, where they are currently being cared for by prisoners working on the farm, in anticipation of restarting the dairy program there.

Dairy or sanctuary?

But not everyone is happy about it. Calvin Neufeld lived next door to the farm at the Collins Bay institution when the fight to save the farms began. “I thought the farms were worth protecting for their benefit to prisoners, who could work outdoors, grow their own food, and benefit from healing interaction with animals,” says Neufeld. “When the farms were coming back, we saw an opportunity to propose an alternative to the former model, essentially taking what was good about the former model and enhancing it, and when we heard there were some academics working on a very similar proposal of animal-assisted therapy and using the prison farms to pilot climate solutions, we came together to form a coalition under the name Evolve Our Prison Farms.”

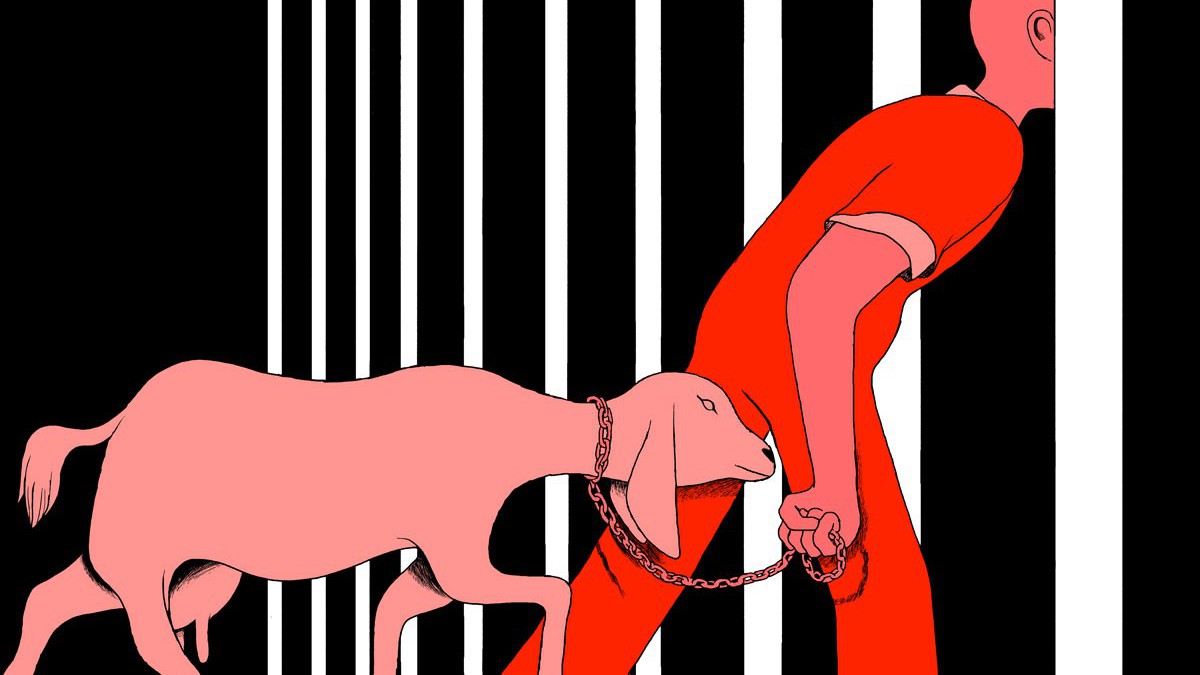

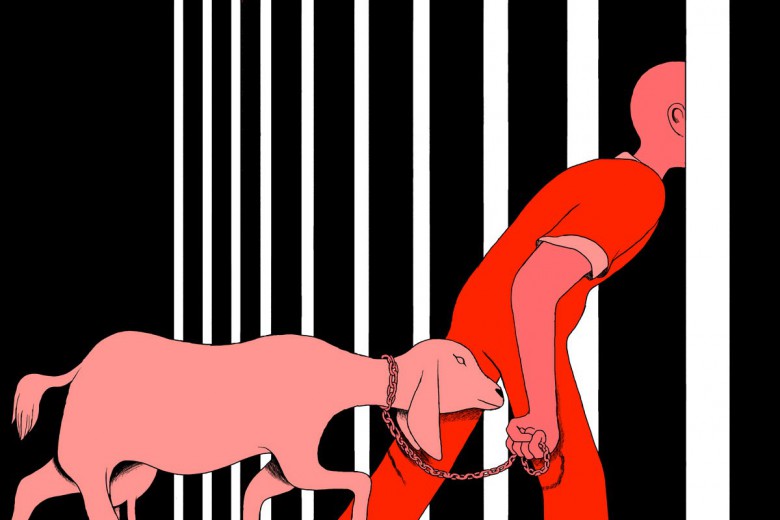

EOPF objects to the way the dairy farm will be run when the program is reinstated. In the current plan, both cows and goats will be raised for milk production on the prison farms. These dairy operations will function as modern industrial dairies, on a fairly large scale and with equipment like milking machines. As in any industrial dairy operation, cows and goats will be bred on a regular schedule, often with artificial insemination. Male offspring, as well as females who aren’t producing enough milk, will be slaughtered for meat. Even with modern equipment, there’s still a lot of labour on a dairy farm: incarcerated workers will take on the day-to-day care of the animals, such as feeding, cleaning barns, bringing animals in for milking, and seeing to the animals’ day-to-day health and safety needs.

Neufeld and EOPF believe that there’s no benefit for incarcerated people in working with animals that are destined for milk production and, ultimately, slaughter.

Neufeld and EOPF believe that there’s no benefit for incarcerated people in working with animals that are destined for milk production and, ultimately, slaughter. Instead, the organization would like to see animals on the farms performing an animal-assisted therapy role – treating them more like pets than farm animals. EOPF hopes to see an operation that involves only plant-based agriculture on the prison farms.

Dowling disagrees that there’s no benefit for prisoners in raising livestock at the farms. “There are ecological and regenerative ways to farm livestock and crops, and there are degenerative, ecology-destroying ways to farm livestock and crops,” she says. “I would like to see the inmates working with agroecological methods, seeing the fullness of the relationship between livestock and land. I think that incarcerated people will benefit from working with animals being raised for livestock agriculture.”

And the experiences of people who worked in the old program bear that out. Briarpatch spoke with Out Of Bounds prison magazine’s former managing editor (who asked that their name be withheld as per the recommendation of their parole officer) about their involvement in the prison farm issue. After being contacted by Neufeld in 2016, says the editor, “I read dozens of letters, articles and testimonials from inmates that participated in the prison farm program. The stories are all very similar. Working around cattle, even cattle meant for slaughter, was redeeming,” they told me. “They cared for something that did not judge, question, or care what they did.”

“I read dozens of letters, articles and testimonials from inmates that participated in the prison farm program. The stories are all very similar. Working around cattle, even cattle meant for slaughter, was redeeming.”

The question of what the farms should look like, and if they should even exist at all, is complex. From a prison abolitionist standpoint, it’s important to improve the quality of life for incarcerated people in the short term while also fighting for the end of all prisons in the long term. If the farm program becomes a way to greenwash the prison system, making it seem that incarcerated people are benefiting from their incarceration through being involved in the farm program, it would be serving reformist functions of extending the reach and longevity of the carceral system.

So, while the debate around whether or not animals ought to be involved in the prison farm program will likely continue, the fact that the Liberals have decided that, for now, they certainly will be, begs important questions of its own.

Production for sale

The restoration of the prison farm programs in the Kingston area has come about largely as a result of broad-based community organizing. But the operation of the newly reopened farms is a far cry from the pre-closure program. While the former program saw incarcerated workers participating in the production of crops, meat, milk, and eggs for use within the prison system, the new farms will focus on production for sale.

One major change in the prison farm system will be the introduction of a large industrial goat dairy operation at Joyceville. Though the federal government initially announced that there would be 2,000 goats producing milk for sale, the size of the goat herd “will gradually be built and will be influenced by operational and market capacities,” according to the CSC. While CSC has been very careful to point out that no contracts have been signed yet, the decision to create an industrial dairy plant happens to come at the same time that both the federal and provincial governments have offered unspecified millions in funding to Feihe International, a Chinese-government-owned corporation registered in the Cayman Islands, to build an infant formula processing plant in Kingston, just a few kilometres from the farm at Joyceville.

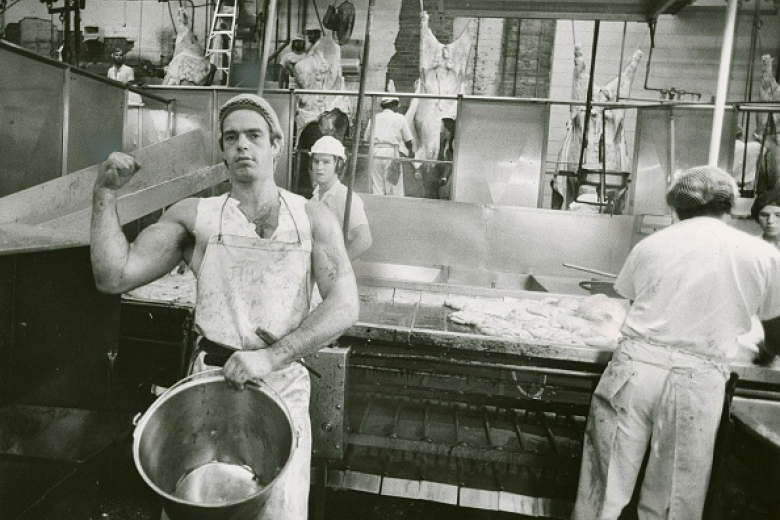

“The prison farm system used to collect milk [and] eggs, and butcher cows, for use in the prisons and the local communities,” says the former Out Of Bounds editor. “Federal prisons used to have fully functioning kitchens. Inmates could learn culinary arts and baking. Around the same time the prison farms were axed by the Harper government’s ‘tough on crime’ stance, so were the kitchens.” Conveniently, those ‘tough on crime’ policies also privatized food services in prisons, handing lucrative contracts to private companies under CSC’s 2014 Food Services Modernization Initiative, to the detriment of those incarcerated.

“Around the same time the prison farms were axed by the Harper government’s ‘tough on crime’ stance, so were the kitchens.”

The change from in-house food preparation to a “cook and chill” model that centralizes production of prison food and distributes pre-prepared food to prisons has been a flashpoint for incarcerated people all over the country. In 2016, for example, incarcerated people at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary protesting the low quality and quantity of food refused to report to work, triggering a lockdown and riot that led to the death of one person. Incarcerated people and their allies have been continuously calling for the return to a model of having fresh food prepared in-house in order to provide sufficient nutritious food for those in federal prisons.

“Everyone has come to realize that the prison farms will no longer feed prisoners at all,” says Neufeld. “So if prison farms can no longer feed prisoners and must supply external markets, then we are now arguing that the program should incorporate some social justice element. Growing produce for shipment to northern Indigenous communities, for example; supplying food banks, hospitals; offer[ing] training in green technologies and techniques … the possibilities are endless.” So why is the reinstated prison farm program not being structured to answer that call?

A lot of that has to do with CORCAN, the federal government-run business arm of the Canadian prison system. Through CORCAN, incarcerated people produce goods and services that are sold to other federal or provincial government agencies, including within the prison system, as well as to the private sector. From industrial laundries and sewing operations to carpentry and other building trades, and now farming, incarcerated people work for a pittance per day with the surplus value created by their labour going to CORCAN. The jobs in the dairy that will be opening at Joyceville will be CORCAN jobs, and the incarcerated people who do them will be paid between $5.25 and $6.90 per day for their work.

The jobs in the dairy that will be opening at Joyceville will be CORCAN jobs, and the incarcerated people who do them will be paid between $5.25 and $6.90 per day for their work.

As a member of the citizen advisory panel, Dowling points out that, in theory, prisoners can choose whether or not to work for CORCAN. But in practice, it’s widely accepted by prisoner justice advocates that the right to refuse work only exists on paper. This came to light in a recent court case where prisoners unsuccessfully fought to overturn a 30 per cent cut to their already meagre CORCAN wages. The case, as well as a nationwide prison labour strike against CORCAN, was triggered by the announcement in 2013 that much of incarcerated workers’ CORCAN wages would be clawed back to cover food and accommodation – workers paying out of their wages for their own incarceration. During that case, incarcerated CORCAN workers testified to being coerced into their work through various means. The former editor of Out Of Bounds, while editing the magazine and also being incarcerated in a federal institution with CORCAN programs, explains that they heard and saw first-hand how workers were coerced into working for CORCAN, with threats ranging from loss of privileges to parole hearing outcomes being affected if workers refused CORCAN labour.

Exporting prison labour products

As much as 85 per cent of the formula produced at the Feihe plant will be shipped back to China to feed an anticipated boom in demand as the country’s one-child policy expires. Whether Feihe gets that milk from prison farms or elsewhere, one thing is clear: the volume of goat milk that will be required by the plant is more than is currently produced in all of Canada. A huge increase in goat’s milk production will be necessary to support the Feihe plant, and it’s worth noting that, while cow’s milk is regulated by supply management in Canada, goat’s milk is not. Canada’s supply management system, which was established through decades of organizing by farmers across the country to prevent shortages and to ensure that farmers are paid a fair price for their product, has been under attack in international trade negotiations since the 1990s. A huge increase in goat’s milk production to support the Feihe plant would create a whole new sector in the province’s dairy industry, one in which farmers’ incomes would not be protected by supply management. So, if the prison farms around the Kingston area do end up producing goat’s milk for Feihe, it could represent a troubling loophole by which a foreign company wiggles around the supply management system that Canadian farmers fought hard to institute – and gains preferred access to a product that’s made under labour conditions that any agricultural workers, indeed workers in general, ought to be concerned about.

The NFU’s Dowling agrees that if the milk from the dairy at Joyceville does end up going to Feihe, it has troubling implications. “I continue to be concerned about the federal government’s focus on exporting Canadian products,” says Dowling. “I would prefer to see the government focus on Canadian agriculture producing for Canadians, including the products of the prison farms. Ideally, the food produced on the farms would be used in the prisons, or within the local region.”

A huge increase in goat’s milk production to support the Feihe plant would create a whole new sector in the province’s dairy industry, one in which farmers’ incomes would not be protected by supply management.

Dowling points out that while the dairy operation ramps up, honey and vegetables are currently being produced for the use and benefit of those incarcerated at the farms: as well as tasks like cropland drainage system repair work at both sites, a small pilot project involving two beehives managed by incarcerated workers was conducted in 2018, and there are now 20 hives at Collins Bay and Joyceville. Workers at the farms have personal gardens and also maintain a large garden for donation to the local food bank and food providers. But the bulk of the production on the newly reinstated farms has been for market. “So far,” says Dowling, “the farm products have been field crop harvests, which were sold on the open market last year; this year, there are cash crops and hay and feed to be harvested for the dairy herd, which is anticipated to be in place by the winter of 2020.”

Regardless of whether or not the goat milk produced at Joyceville goes to the Feihe plant or elsewhere, there are still a lot of reasons to be concerned about how the labour of incarcerated workers is being organized on the farms. “The prison farm system was, for the most part, a fundamentally rehabilitative program for those who embraced it,” says the former Out Of Bounds editor. “From working with the animals, feeding and caring for them, to learning skills from the farmers and staff that ran the farms, the inmates that participated were surrounded by a nurturing environment, unlike [anything] they had ever known. Some inmates stated that they had never cared for anything, ever, until they worked with the cows on the farm.”

But with the shift in focus toward industrialized production for sale on the open market, the former Out Of Bounds editor believes that those benefits will no longer exist. “Industrial farming is all about maximizing the yield. Each goat is to produce X amount of milk in X amount of days, ensuring that costs stay down, production runs at max, and that’s it. There is no provision for the inmates to commune with the animals.” And instead of the products of that labour going to the people who do the work, the surplus value created by incarcerated workers’ labour will be creating income for CORCAN – regardless of the fact that the agency has never posted a profit in all the time that it has existed, and in fact regularly costs more to run than it produces – money that advocates say would be better put into improving education, food, and housing for incarcerated people.

The prison farms as they’ve been reconstituted fit into the increasing neoliberalization of both agriculture and incarceration by channelling the labour of incarcerated people into a low-paid workforce that seems likely to engage in farm activities primarily for corporate profits.

As a farmer myself, I’m concerned that the potential benefits of farming being touted by the government will greenwash a carceral state that coerces incarcerated workers into producing for exchange instead of for their own benefit, and then steals the surplus value created by their labour. If incarcerated workers on CORCAN-run farms are working in conditions of absolute lack of control over their labour – no unions, no benefits, crumbs for wages, bringing the logic of incarceration into agricultural work – then I know that the value of my labour is likely to suffer. And if the products of that labour are going to a private corporation that will export them out of the country, and will do so with both federal and provincial government funding their infrastructure, I’m concerned about that cozy relationship between a private-sector business and the branch of the government that has absolute power over the lives and labour of incarcerated people.

It’s tempting to celebrate the return of a program that promises to create both environmental and social benefits out of incarceration. But at the end of the day, a prison is still a prison. The prison farms as they’ve been reconstituted fit into the increasing neoliberalization of both agriculture and incarceration by channelling the labour of incarcerated people into a low-paid workforce that seems likely to engage in farm activities primarily for corporate profits. Talk of the rehabilitative benefits of the prison farms can easily fit into a reformist narrative in which incarceration is justified as a way to “fix” people labelled as criminals, and the small improvements in the lives of incarcerated people that might be created by the program can be used to distract from the fundamental injustice of warehousing criminalized and marginalized people in the prison system.

“People on the outside need to do a host of things,” says the former editor of Out Of Bounds. “Educate themselves, get involved, stop presuming all inmates are savages, work for rehabilitation, pound on the doors of those officials that can make a difference. Don’t stop doing it when it gets hard.” The return of the prison farms is not the end of the fight, but rather an opening of new ground on which to keep fighting for real justice.

Editor’s note: This article originally stated that EOPF hopes to see an entirely vegan operation on the prison farms, tied to a larger program of offering plant-based food in the prison system as a whole. In fact, while EOPF does advocate for plant-based agriculture alongside animal-assisted therapy in prison farms, EOPF’s work does not involve advocacy on what food should be offered within the prison system.

This article originally stated that incarcerated people working on the prison farms would be paid $1.95 per day for their work. In fact, they will be paid between $5.25 and $6.90 per day.

This article originally stated that there will be approximately 2,000 goats at the industrial goat dairy operation at Joyceville. In fact, the size of the goat herd is yet undetermined.