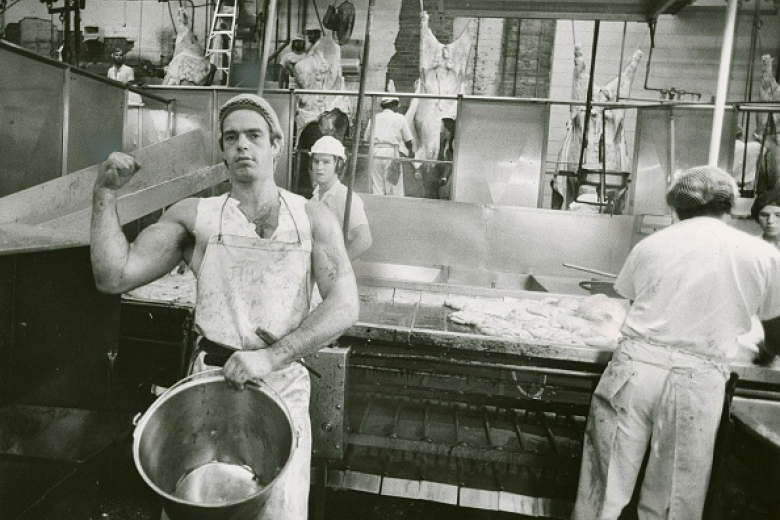

In a speech to the First International Working Men’s Association in 1865, Karl Marx set out to dispute the argument made by fellow socialist John Weston that “a general rise in the rate of wages would be of no use to the workers [because owners would employ fewer workers]; … therefore, the trade unions have a harmful effect.” Marx argued that the tension between workers’ wages and capitalists’ profits can only be settled “by the continuous struggle between capital and labour, the capitalist constantly tending to reduce wages to their physical minimum, and to extend the working day to its physical maximum, while the working man [sic] constantly presses in the opposite direction. The matter resolves itself into a question of the respective powers of the combatants” [emphasis mine].

Marx was right. We don’t need to look hard for contemporary evidence that capitalists always seek to exploit their workers by driving down pay and maximizing the length and intensity of the working day: the Fight for $15 and Fairness campaign (Karim, “Everything Goes Up But Pay”) wants to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour, create freer conditions for unionization, and guarantee sick days. In short, workers are organizing for humane working conditions that will lift them out of poverty.

But judging from the red-hot reaction of the capitalist elite, these demands will hasten the business apocalypse. In the National Post, columnist and Fraser Institute staffer Philip Cross predicts, “Even if a well-intentioned but naïve employer hires workers at a cost that exceeds their productivity, by definition the firm will lose money and eventually go bankrupt.” (The fear mongering is best countered with measured economic research like the CCPA’s studies on minimum wage increases or RankandFile.ca’s handbook for organizers, $15 and Fairness Now!)

If Marx is correct about the importance of the power of combatants, workers have cause for concern. Between 1981 and 2012, overall unionization in Canada declined from 38 per cent to 30 per cent, most steeply in the 1990s, and most pointedly in the private sector and among young men. Work stoppages also declined. From an average of 754 in the 1980s, the frequency of work stoppages fell to 393 in the 1990s, and 258 in the 2000s.

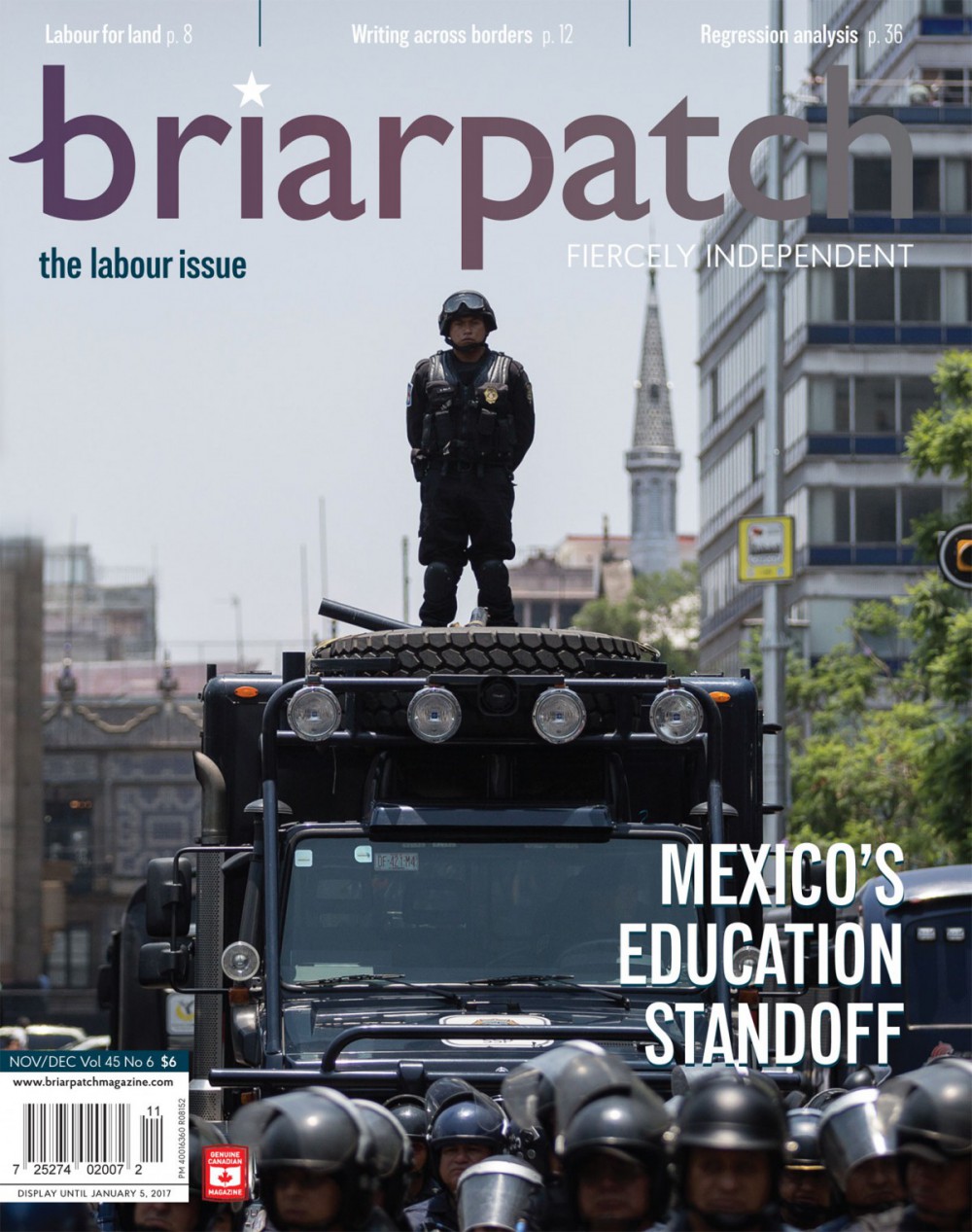

To make matters worse, the response of capitalists to labour’s tactics is almost always repressive: if the political capitalist class, propped up by the police and/or military, isn’t killing strikers (Mitchell, “Mexico’s Education Standoff”), it arbitrates employer-friendly agreements (Fuatai, “Challenging the Mail Gaze”) or legislates strikers back to work. Businesses hire replacement workers (Collins, “Regression Analysis”) and demonize workers through corporate-compliant news media that amplifies and distributes their PR.

But this isn’t entirely a bad-news story; the working class is developing its own political analysis, innovative strategies and tactics, and connections between struggles. A rich history of labour analysis by feminists, Indigenous peoples, and racialized folks yields an understanding of the labour struggle broader than the traditional focus on unionized and remunerated workers.

Let’s take Poland’s recent Czarny Poniedziałek strike, when 100,000 feminists withdrew their paid and domestic labour to protest the government’s draconian proposal to altogether eliminate the right to abortion. Strikers used a traditional work stoppage to illuminate that capitalism depends on a reproduction of the working class. “Struggles over social reproduction are virtually ubiquitous,” feminist socialist Nancy Fraser says. “They just don’t carry that label. But if it came to pass that these struggles did understand themselves in this way, there would be a powerful basis for linking them together in a broad movement for social transformation.”

For another example, take the nationally coordinated U.S. prisoners’ strike against prison labour that began on September 9, 2016, the 45th anniversary of the Attica uprising. “We understood that our incarceration was … about our labour and the money that was being generated through the prison system,” an inmate named Kinetic Justice explains. “It is not ‘slave-like conditions’ in prison labour – this is actually institutional slavery.”

The Intercept reports that prison labour is “a $2 billion a year industry that employs nearly 900,000 prisoners while paying them a few cents an hour in some states, and nothing at all in others.” Inmates, many of whom are card-carrying members of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (an arm of the Industrial Workers of the World), are using carceral labour as a chokepoint. It’s too early to tell whether the prison-industrial system will capitulate to inmates’ demands, but their tactics deserve broad international union solidarity.

Plenty of examples illuminate how working class analysis is strengthened by the understanding of a complex, multitudinous, and stratified working class. Our annual labour issue contributes to an understanding of capitalism in its interaction with colonialism (Kesiqnaeh and Pflug-Back, “Accumulation by Dispossession”; McCallum, “The Indigenous Nurses Who Decolonized Health Care”), gender and race (Karim), social reproduction (Mitchell, “The Kids are All Right”), and legislation (Collins). Broad working class analysis will build our power.