Wenting Li

For the past year, low-income Asian women in Newmarket, Ontario have been engaged in a fierce battle with the town’s council, which has been working to close down their massage businesses by claiming that the workers are both disreputable criminals and sex trafficking victims. Despite months of opposition by workers and human rights organizations, in January 2022 the town council imposed a set of regulations requiring massage businesses to get a new type of licence.

How could the town of Newmarket get away with such a racist and classist policy that singled out Asian businesses and threw an entire sector of low-income Asian women out of work during a pandemic?

Instead of supporting these businesses during the pandemic, the town of Newmarket ordered them to obtain a licence or cease all business operations by April 2022. As of April, not one of the town’s existing Asian massage businesses had been granted the licence. Bylaw enforcement officers visited the businesses to order their closure and threatened to impose extremely harsh fines of $4,000 to $5,000 per day on these small businesses for non-compliance.

How could the town of Newmarket get away with such a racist and classist policy that singled out Asian businesses and threw an entire sector of low-income Asian women out of work during a pandemic? By using a fake anti-trafficking campaign, along with zealous support from anti-trafficking NGOs, the police, and the media.

“Cleaning up” Newmarket

To understand how we got here (and what we can do about it) we have to go back to early 2021, when the town of Newmarket suddenly announced that they were planning a “cleanup” of the town’s body rub businesses. Under the town’s regulations at the time, a “body rub parlour” was any business that offers massages by those who are not registered massage therapists. This meant that all massage spas and wellness centres in Newmarket were body rubs, but almost all were operating illegally because the town would not issue any more than two body rub licences for the whole town. The businesses were also subject to zoning restrictions that forced them to operate in a remote industrial area of the town.

Newmarket could have just removed the cap on body rub licences and the zoning restrictions. But thanks to centuries of racism and employment segregation in North America, body rubs are unfairly associated with crime, sex work, and people of colour. Instead, Newmarket town council declared their intention to create new rules that would drive out the businesses that they defined as “appeal[ing] to sexual appetites,” and the “brothels” that town councillors claimed were “hosts for human trafficking.” Their anti-trafficking plan was to get rid of suspected sex work by tightening the rules so that only businesses whose workers have formal educational certifications from Canada could get the newly created Personal Wellness Establishment Licence. The town could also require interviews with business owners and on-site inspections. Canadian college certifications can take years, are offered only in English and French, and tuition can cost thousands of dollars.

In April 2022, when Newmarket’s new rules came into effect, the town staff decided that not one Asian business met the new criteria.

It quickly became clear to Asian women massage workers that this was not about protecting them from human trafficking – this was an attempt to push them out of work. The town council seemed to consider Asian massage workers to be both sex workers and human trafficking victims. And their demand for a Canadian-only education would put the licences completely out of reach for low-income women who have trained in other countries or on the job.

The workers had reason to be concerned: in April 2022, when Newmarket’s new rules came into effect, the town staff decided that not one Asian business met the new criteria. Through personal communication, we were made aware that every single one had been forced to shut down and threatened with legal action and fines if they stayed open.

A fake anti-trafficking campaign

The fight in Newmarket reveals what we have known for decades: that so-called “anti-trafficking policies” are a cover for right-wing xenophobia, racism, and anti-sex work economic and social control. In a fake anti-trafficking campaign, right-wing actors – politicians, conservative churches, carceral feminists, and the police – work together to target a business that is associated with sex work, one usually dominated by workers of colour, claiming that the target is a front for sex trafficking. The leaders of the campaign make this claim seem credible by scaring people with propaganda that alleges extreme violence and by invoking hateful stereotypes that tie the targeted group to slavery and corruption. The anti-trafficking campaigners craft a policy (and an enforcement strategy) that criminalizes the target and suppresses any opposition while claiming to protect public safety.

This is exactly what happened in Newmarket. At least two local advocacy groups had been pressing to ban Newmarket’s massage businesses and arrest people: Parents Against Child Trafficking (PACT) and the Council of Women Against Sex Trafficking in York Region. PACT describes itself as “lawyers, communications experts and entrepreneurs” and claims that its goal is to prevent grotesque and bizarre forms of violence that they link to sex work and the massage industry: “to protect our kids, our neighbour’s kids, your friends’ kids from being lured, recruited, drugged, kidnapped by predators who then use them as non-consensual sex workers in hotels, motels, truck stops body rub Parlours, massage spas, wellness centres and online porn sites.” Their solution? Shut down a largely-immigrant labour sector: the unregistered massage industry. “Provinces MUST SHUT DOWN Body Rub Parlours!” their website reads. Their page on massage businesses features pictures of Asian women and describes body rub operators as “pimps.”

In a fake anti-trafficking campaign, right-wing actors – politicians, conservative churches, carceral feminists, and the police – work together to target a business that is associated with sex work, one usually dominated by workers of colour, claiming that the target is a front for sex trafficking.

These NGOs do not seek to end human trafficking or even child abuse. If they did, they’d combat violence in the home and fight for labour rights for migrant workers. What they actually oppose is those poor and racialized women they suspect of being sex workers.

So when Newmarket town council introduced their proposed changes, most of the work had already been done for them. The town councillors didn’t need to provide evidence for their claims about human trafficking or prove that their new rules would stop violence. The town’s mostly white residents were already prepared to believe wild stories about how sex trafficking gangs had infiltrated their small town and were coming for their children.

In early 2021, in one of the first news stories about the proposed policy, Newmarket manager of regulatory services Flynn Scott told the Toronto Star that “over the last two years, Newmarket’s bylaw officers have laid charges against seven body rub parlours” and that “[b]ased on our conversations with YRP [York Regional Police], we have been made aware there is a significant human trafficking component to these body rub parlours and it is prevalent here in Newmarket.” But human trafficking is a criminal offence, not a municipal bylaw infraction. The Star’s reporter then spoke to York Regional Police, who said there were no charges of human trafficking against the body rub parlours – but that “we have seen it occur in the past throughout the region.” The reporter accepted police statements as evidence and did not interview any workers, nor did she ask if the town council planned to.

Not a single massage worker was asked to verify any of this information – they were not asked whether they were being tied up with rope, whether they were abused by sex traffickers, or whether they wanted their workplaces banned.

Subsequent news articles saw councillors Trevor Morrison and Grace Simon repeat the claim that the town’s massage businesses were being used for human trafficking. One of these stories, published in NewmarketToday, was accompanied by a stock photo of a person’s hands bound by rope. In another Toronto Star article, Casandra Diamond, the director of a Christian anti-trafficking organization, described women in strip clubs and massage businesses as being “purchased” – as though they were enslaved – again without providing any evidence.

Not a single massage worker was asked to verify any of this information – they were not asked whether they were being tied up with rope, whether they were abused by sex traffickers, or whether they wanted their workplaces banned.

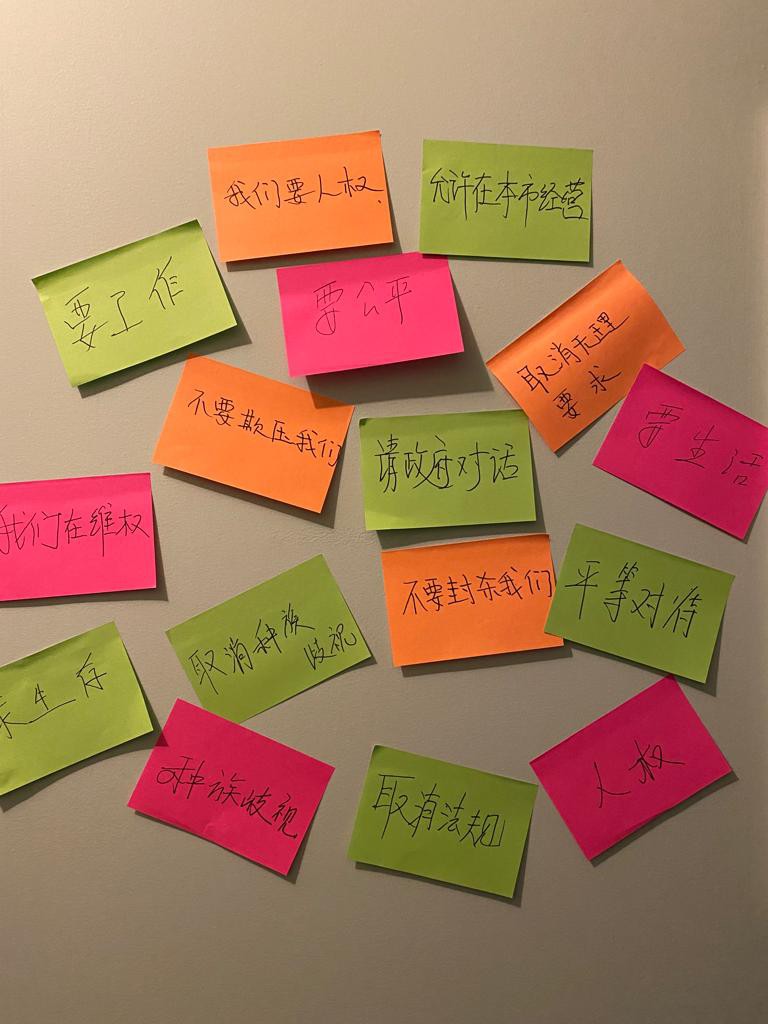

Post-it notes with messages from Asian massage workers in Newmarket, including "We demand human rights," "Our business should be allowed in the city," and "Eliminate racism." Photo courtesy of the authors.

The sham consultation

In the spring of 2021, Newmarket held a series of public meetings to appear to be consulting affected stakeholders. Massage workers reported to us that town staff had sent an email to some of the business owners – but none of the workers knew about the consultation. The town’s information about the consultations was posted on their website in English only. Butterfly: Asian and Migrant Sex Workers Support Network – an organization that one of this article’s authors, Elene Lam, founded – scrambled to get the information about the consultations out to Asian workers so they could participate.

Throughout the process of reviewing the town’s body rub rules, we witnessed what we call “the anti-trafficking catch-22.” In an anti-trafficking campaign, women of colour are portrayed as brainwashed and ignorant sex trafficking victims, speaking under the control of pimps, not capable of acting of their own free will. Anti-trafficking campaigners use this argument to claim that their repressive policies protect vulnerable women from human traffickers. But when the women themselves refute this and demonstrate that they are not human trafficking victims, anti-trafficking campaigns switch tactics and portray people of colour as nefarious criminals whose sexual immorality is a threat. This way they can claim that their policies protect the public from dangerous outsiders.

Diamond described Asian women as people “who [don’t] even speak enough English to consent to sex.” Councillor Simon later called Diamond a “personal good friend.”

In the consultations (at which both of the authors spoke), white councillors and anti-trafficking NGOs frequently referred to Newmarket’s “values” and “community standards” in ways that positioned Asian women and suspected sex workers as a threat. Mayor John Taylor said, “I don’t want to send a message to our community that prostitution or sex work is acceptable. I don’t want to send that message to my daughter.” Deputy mayor Tom Vegh said, “I think we really just want to drive it out of our town, quite frankly. I don’t think it’s consistent with the values of our town.” Manager of regulatory services Flynn Scott and licensing officer John Comeau described the consultation process’s goal to “raise the standards of our community.” After Elene Lam spoke against the ban, Casandra Diamond said of Lam: “the attempt is to sell sex – clearly, as Miss Lam already told you she wishes to do, and why she’s invested here in your community, my community.”

Over and over, Chinese people were presented as corrupt villains or helpless victims. Diamond discredited Chinese educational credentials, saying, “I assure you the diploma mill is actually in mainland China” and claiming that “I know people who get off the plane [from China] as soon as they land in either Toronto or Vancouver and they are taken directly after the flight, not having eaten, to a massage parlour where they will now start servicing men.” Diamond described Asian women as people “who [don’t] even speak enough English to consent to sex.” Councillor Simon later called Diamond a “personal good friend.” No town staff or councillors challenged these racist allegations.

In the face of this overt racism, Asian massage workers showed up to the consultations ready to fight for their livelihood. Women in their 40s, 50s, and 60s provided first-hand testimony about conditions in their workplaces, confirming that they were not trafficked. They described massage work as relatively relaxed, describing how the flexible working hours, friendly colleagues, and freedom to rest when there are no customers made massage work more suitable for their age and physical condition than other jobs.

"We are old and have language barriers, how can we meet the new training requirements?"

Mei, age 52, told town councillors, “After hearing about Newmarket’s new regulations, I was really angry. I think this is a double discrimination: racial discrimination and industry discrimination. We are old and have language barriers, how can we meet the new training requirements? We will have no income during class time [the training period for certification] and cannot live or pay rent.”

Ivy Chan, age 40, told the local media, “I want the town to not oppress us,” adding that the pandemic has made it “very difficult to survive already.” In the consultations, Chan explained how she developed her massage skills through on-the-job training that would not be recognized under the new licensing system: “I had trained eight to nine hours a day, practised with colleagues without any breaks. I have learned the techniques of back, head, and neck massages, oil pushing, sand scraping, and hot stones respectively for three months.”

Dozens of organizations and individuals registered their opposition to the new rules and the harm they would cause to Asian businesses and workers. The groups included local residents, a women’s anti-violence organization, two national legal advocacy organizations, university professors, Asian women’s organizations, and human rights, racial justice, and labour organizations. The Newmarket town councillors responded that the pushback against their racism had been harmful to them. Mayor John Taylor said references to racism were “rude and disrespectful,” and that “these attacks are of such a personal nature that they have, in my eyes, introduced a new low point in our council chamber.”

Community members rally in support of Asian massage workers in Newmarket. Some community members' faces have been anonymized to protect their privacy. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The Trojan horse of anti-trafficking policies

The body rub ban has nothing to do with safety or stopping human trafficking. Anti-trafficking policies like this are just one tactic among many that Western governments use to keep migrant people of colour out of better-paying work and in the place assigned to them – to serve as a cheap, pliant workforce.

In the Newmarket process, we see that once Asian women are defined as victims or criminals, forcing them into lower-paid service work becomes acceptable, even admirable. In the Newmarket consultations, town councillor Christina Bisanz proposed that the review underway was an “opportunity,” saying, “In York region alone, we can expect there will be close to a thousand new long-term beds being built. At a time when we have a severe shortage of personal support workers – severe shortage of personal support workers – I don’t know how we are going to staff all these new beds. Maybe this is an opportunity for us to look at how we can redeploy these very caring, very professional people into a job where they are absolutely needed.” The severe shortage of personal support workers is in large part because these are terrible jobs. Non-English speaking migrant women in these facilities earn pitiful wages and face high rates of employment precarity, racist discrimination, and injury.

Anti-trafficking policies like this are just one tactic among many that Western governments use to keep migrant people of colour out of better-paying work and in the place assigned to them – to serve as a cheap, pliant workforce.

Anti-trafficking campaigns are inextricably linked to and powered by rich white people’s entitlement to the cheap and precarious labour of women of colour. They reverse social and economic progress being made by working class, migrant, and Asian communities. They allow the ruling class to push migrant and Asian people out of neighbourhoods or to have them deported. They give developers access to vacated properties and eliminate competition with white businesses. They coerce working-class Asian and migrant women back into lower-paid and more demanding jobs in white households as domestic workers or in restaurants and care facilities as service workers. They allow the police and government to seize cash and property from migrant businesses and to generate revenue through fines. They help justify the over-inflated budgets of police and border control. They defend a white supremacist social order where white people make the rules and the money.

We need more of our allies to refuse the Trojan horse of anti-trafficking policies and prevent them from spreading to other cities and towns.

Low-income Asian women in Newmarket are continuing to fight back and they want our help. They are planning direct actions and inviting their allies to sign this open letter demanding that the town of Newmarket end racism against Asian massage businesses and workers.

Lisa, a 61-year-old massage worker in Toronto, said it best: “I understand that it is not something that can be done in a day or two to fight against the government and society's discrimination against our industry. But we must still unite and fight for our own interests.”

This article is an edited draft of a chapter from the authors’ forthcoming book about the anti-trafficking industry, to be published by Haymarket Books.

Update, May 11, 2022: This article originally stated that the Town of Newmarket requires Personal Wellness Attendants to have Canadian certifications that can take weeks to obtain. In actuality, the Town of Newmarket has rejected applicants with Canadian certifications from weeks-long courses – but has accepted Canadian college certifications that take two years and cost over $4,000 for domestic students. This article has been updated to reflect this information.