When Heder’s boss refused to pay him and his son Alex the week of wages they were owed, they didn’t know where to turn.

Heder* and Alex* are migrant workers and, to make ends meet, they work under the table. Most recently, they were working on a construction site when, partway through a project in 2023, their boss fired them.

Heder knew he couldn’t challenge his firing, but he was determined to get his and his son’s last paycheques, so he confronted his boss on the construction site. But his boss refused and “became very violent,” Heder says.

In the 2021-2022 fiscal year, Ontario employers stole at least $9 million in workers’ wages.

Images of deportation and police trouble flashed through Heder’s head as his boss yelled at him, ultimately threatening to call the police on him, insisting that Heder and his son “had no rights.”

That line is one that Veronica Zaragoza has heard dozens of times. She’s an organizer at Toronto’s Workers’ Action Centre (WAC), where she hosts labour rights and organizing workshops for the Latinx community and undocumented workers. That’s how she, Heder, and Alex met, and together, they began to formulate a plan get Heder and Alex’s wages back.

Workers’ action centre history

“It’s really astonishing to me that more of these worker centres don’t exist,” says Erin Carr, the executive director of Solidarity Place Worker Education Centre in Hamilton. Despite being Canada’s most populous province, Ontario has only a handful of WACs. “For a province of this size, there is clearly a service gap that exists.”

Like Heder and Alex, most workers who reach out to Hamilton’s Solidarity Place are dealing with issues that are covered under the “bare minimum” standards of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act like wage theft, severance pay, how often wages are paid, inadequate breaks, and other basic standards, says Carr. “Even those basic, minimum standards are often just flouted, and not communicated to employees correctly.”

Much of Carr’s work is helping workers navigate the bureaucratic system to enforce their rights. While helping put together an official complaint might not be glamourous work, the scale at which basic labour rights are flouted proves its necessity. For example, in the 2021-2022 fiscal year alone, Ontario employers stole at least $9 million in workers’ wages.

“Even those basic, minimum standards are often just flouted, and not communicated to employees correctly.”

The WAC model is very different from traditional trade union methods of worker organizing, negotiating collective agreements, and settling grievances. WACs work with non-unionized workers which means they have two options: guide workers through formal channels, like making a complaint to the Ministry of Labour or the human rights commission (which can take up to eight months) or use informal channels, like organizing a phone zap where supporters tie up an employer’s phone lines to pressure them into paying stolen wages.

WACs have always served workers in low-wage, precarious work. In the U.S. during deindustrialization in the 1980s and 1990s, manufacturing and resource extraction jobs, which had strong labour unions and worker protections, were replaced with service and retail jobs, often without the same protections, benefits, or wages. At the same time, thousands of immigrants were working in these low-wage sectors, where they faced racial discrimination and other workplace abuses. With the erosion of wages and union power leading to further exploitation, workers and community organizers formed Workers’ Action Centres to support these non-unionized, precariously employed workers.

Between 20,000 to as many as 500,000 people are undocumented in Canada

WACs’ history is similar in Canada. Hamilton’s Solidarity Place was formed in 1995 with seed funding from the province. Hamilton’s manufacturing sector was in decline, and the rest of the province was in a recession. “At the time we were incorporated, a lot of our work had to do with retraining, upskilling, helping folks who had been laid off because of these major macro changes in the economy,” says Carr.

After a long period of dormancy and a move to a new location, today Solidarity Place is running again. Like other WACs, the centre is tasked with organizing the growing pool of undocumented, migrant, and precariously employed workers.

While there are no accurate figures on the number of undocumented people in Canada, various academic sources surveyed in March 2022 estimate that between 20,000 to as many as 500,000 people are undocumented. They’re an appealing pool of workers to employers looking to save on labour costs. Undocumented workers’ precarious immigration status forces them to take on work that pays under the table, meaning their employers can skirt minimum wage laws and save on employer contributions to Employment Insurance and the Canada Pension Plan.

The first thing an undocumented worker thinks is: ‘because I don’t have a work permit or because I’m working by cash, or because I don’t have status, I don’t have rights.’”

The Migrant Rights Network estimates that there are at least 1.6 million people in Canada living undocumented or with a precarious immigration status. The Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and other, more specialized programs supply multiple sectors like agriculture, health care, construction, and retail with low-wage workers, allowing businesses to maximize their profit margins at the expense of workers with an uncertain future in Canada. From January 1, 2023, to August 31, 2023, Canada approved 692,760 permits under the TFWP and the International Mobility Program, a sharp increase from 274,690 in the same period in 2022.

These programs have “closed” permits, which means their immigration status is tied to their employment; changing jobs or staying in Canada after the permit expires requires workers to apply for a new work permit or risk becoming undocumented. In a submission to the House of Commons, the Migrant Rights Network called closed permits a form of “indentured labour” because employers have outsized control over their employees’ life and immigration status.

Organizing creatively

Zaragoza came to Canada as a refugee claimant, but the Canadian government denied her claim.

“I had to fight for my legal status, so I started to work in many precarious jobs,” says Zaragoza, who worked as a cleaner for more than a decade. Forced to work under the table, her job options were limited, and her bosses knew that.

“I confronted by myself many labour exploitations,” she recalls. But she didn’t want to stand up to bosses on her own anymore, so she went to Toronto’s WAC to learn about her rights and how to organize. For three years now, she’s been working as an organizer at the WAC, equipping other Latinx and undocumented workers with the same lessons she learned.

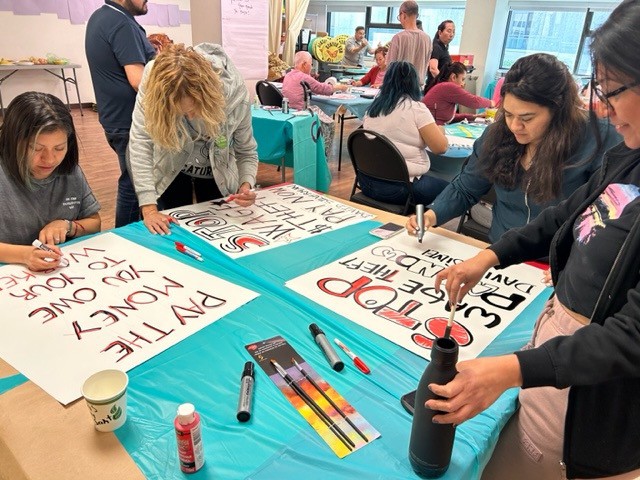

Workers make posters demanding their employers pay them the wages they are owed at Toronto’s Workers’ Action Centre. Photo courtesy of Veronica Zaragoza.

“The first thing an undocumented worker thinks is: ‘because I don’t have a work permit or because I’m working by cash, or because I don’t have status, I don’t have rights.’”

Zaragoza believes that a lack of political education makes it difficult to organize migrant, undocumented, or otherwise precarious workers. For example, she often works with people from countries where labour organizing is much more dangerous. Workers also often worry that their employer will have them deported if they speak out against their unfair working conditions.

In his training sessions, Carr tries to not only educate workers about their rights, but also about labour history and how other workers have won better conditions: “I try to incorporate a history of the workers’ movement, a history of the labour movement. This is to say that these rights – in many cases, inadequate – are the result of protracted struggles of workers. Ultimately, the most important thing you can do as a worker to get more dignity and justice is organizing with your fellow workers, whether that’s the final step of creating a union or the development of more informal methods.”

Worker organizations like WACs organize and mobilize precarious workers that unions largely aren’t reaching or organizing.

Carr insists that the labour movement needs to start “being more creative about how we talk to working people. We need to actually put resources and some skin in the game in talking to folks who might not be already organized in a union.”

One hurdle to organizing migrant and undocumented workers is finding them. One way Solidarity Place connects with new workers is through their free tax clinic, which they run in part to offer an essential service, but also to broach conversations about labour rights with non-organized workers.

“A lot of the folks that utilize our tax clinic are newcomers. And oftentimes, it’s the first time they’re ever hearing about their rights as a worker in Ontario,” says Carr. If the labour movement wants to reach precariously employed workers, Carr insists that unconventional tactics like the clinic, which meets workers where they are at, are essential to building collective power.

Workers also often worry that their employer will have them deported if they speak out against their unfair working conditions.

As American trade unionist and scholar Jane McAlevey famously argues, a great deal of labour organizing is about raising expectations. Better pay and working conditions, and respect in the workplace can seem unattainable, especially if workers have never heard of or experienced anything but exploitation. Worker organizations like WACs organize and mobilize precarious workers that unions largely aren’t reaching or organizing.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, social justice group the Commont Front NL saw a need in their community to organize non-unionized workers. The group is most known for their Fight for $15 and Fairness campaign, which advocated for a higher minimum wage in the province. The workers the group met during that campaign inspired them to establish their own Workers’ Action Network (WAN) in St. John’s in 2022 with some seed money from trade unions, recalls Mark Nichols, a WAN organizer.

Mark Nichols (centre) does worker outreach at the St. John’s Farmers Market. Photo by Tania Heath.

Like the centres in Hamilton and Toronto, the WAN helps workers to stand up to abusive and illegal treatment from their bosses. But the WAN also organizes against workplace mistreatments that aren’t covered by labour legislation. In some cases, workers’ rights are “not being violated. They’re being treated badly but it doesn’t actually break a law,” Nichols explains.

In these cases, the WAN mobilizes the community to pressure employers. For example, in the summer of 2023, Heather Blanchard was at risk of losing her position at the Bell Island senior’s complex when the board tendered it off for bids rather than classify her as an employee. The WAN circulated a petition to rally community support for Blanchard, letting her employer know that the community stood behind her and was watching the employer’s next move. The WAN supported Blanchard even as the employer continued with her replacement.

Despite the important role the WAN played in the community, in October 2023, the WAN’s seed funding was depleted and they had to eliminate paid staff positions and transition to a volunteer model in order to preserve their already scarce resources and continue operations.

Solidarity Place faces similar challenges; Carr is the only full-time employee. Both Nichols and Carr are hesitant to accept funding from federal and provincial governments, as it could limit their political advocacy and ability to criticize governments, which are integral to the mission of both organizations.

Winning back stolen wages

With Zaragoza and another WAC staff member by their side, Heder and Alex decided to confront their former boss again, this time at his house. They planned to serve him a demand letter and calmly ask for their stolen wages to be paid. Zaragoza calls this a “delegation visit” – a tactic the WAC uses often to pressure an employer into a settlement.

But once they got there, their boss began yelling at and threatening the group, and eventually he called the police.

When the police were called, “the first thing that came to my mind,” says Heder, “was that we were a huge and terrible problem. I was feeling really terrified, not only for myself, but for my son too because we were together there.”

“That was one of the hardest delegation visits we had,” adds Zaragoza. “That kind of situation for migrants, to have police involved, means ‘maybe they’re going to take me to jail, maybe they’re going to deport me.’ You don’t know what’s going on, because many in our community have bad experiences with the police.”

Heder continues: “What’s next? Maybe they’re going to take us?”

Heder and his delegation spoke to the police, and, after two hours outside the employer’s residence, the police allowed them to serve his former boss the letter.

The boss still didn’t give Heder and Alex their paycheques after the visit, so Heder and Zaragoza filed a complaint to the Ministry of Labour. After an appeal and mediation, Heder and his son recouped 85 per cent of their stolen wages.

“I was so happy receiving the money,” Heder recalls. “We actually needed it.”

*Heder and Alex are using pseudonyms for safety reasons. Heder’s quotes have been translated from Spanish by Veronica Zaragoza.

_at_the_2023_May_Day_Rally_at_Harbourside_Park,_St._Johns,_NL__1200_675_90_s_c1_.jpg)