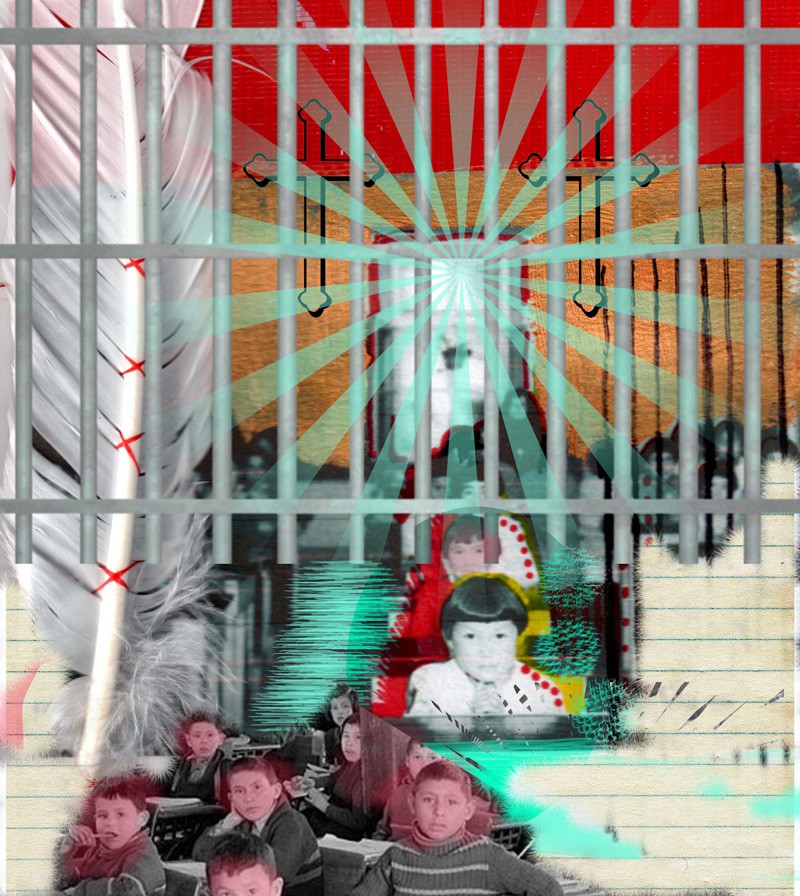

Tania Willard

One kilometre west of the city of Prince Albert, the federal Saskatchewan Penitentiary sits on the site of a former residential school run by the Anglican Church of Canada. As in other prisons across the Prairie provinces, the 20-acre facility houses inmates predominantly of Aboriginal descent. This situation is not unique: Indigenous people represent only three per cent of Canada’s population yet account for 17 per cent of its prison population. As the last of the residential schools have shut down, penitentiaries have become the new form of containment for Indigenous people in Canada. In a 1988 study prepared for the Canadian Bar Association, Aboriginal rights advocate Michael Jackson stated: “The prison has become for many young native people the contemporary equivalent of what the Indian residential school represented for their parents.” Almost 25 years later, young Aboriginal men in Saskatchewan are now more likely to go to prison than to finish high school.

Despite the considerable attention these statistics have received, rarely do we consider them in the context of an ongoing colonial project. We must question how it is that Aboriginal people become tangled up in the justice system at all and why it is that prisons have come to be viewed, in the words of Angela Davis, as an “inevitable and permanent feature of our social lives.” How do institutions like schools, which are presented as disconnected from – or even antagonistic to – incarceration, shape a future of imprisonment for Aboriginal youth in Canada?

Dangerous and unruly

Dominant narratives suggest that disparities in incarceration are the result of individual shortcomings and moral deficiencies. One reader’s comments on a CBC news article on Aboriginal incarceration nicely summarize common attitudes surrounding the issue: “Excuse me. Who is stopping aboriginal people from getting an education? Who is forcing aboriginal people to break the law and commit crime? If one does not break the law, and if one does not commit crime, one does not go to jail.”

Mainstream media plays a central role in driving these discourses. Joyce Green, a researcher on Indigenous-settler relations, says, “For the most part, Aboriginal peoples do not exist for the media, except as practitioners of violence or political opposition, as marketing stereotypes, or as bearers of social pathologies.”

The construction of European settlers as benevolent saviours and of Native people as ungrateful degenerates was necessary to justify the theft of Indigenous land and resources. This is all too often forgotten, as are the continued privileges settlers secure from casting Aboriginal people as dangerous and unruly. It is time to shift the focus from the colonized to the colonizers, and to interrogate the interlocking systems that allow the over-incarceration of Indigenous people to continue.

The school-to-prison pipeline

Canada’s education system, imposed upon Indigenous people for hundreds of years, plays a powerful role in constructing the notion of public enemies in need of discipline and containment. The assumption that the education system today is devoid of its oppressive and violent past unfairly lets schools off the hook. Links between education and incarceration for Indigenous people in Canada are rarely made beyond pointing out that many Aboriginal people in custody are under-educated, often without high school diplomas. Education is touted as an immediate, attractive, and available alternative to youth wishing to avoid so-called criminal activities. While improving levels of education for Indigenous youth is important, we must also scrutinize the education youth are receiving. By assuming that classrooms are neutral, apolitical spaces, schools risk pushing the same colonial agenda that Aboriginal education was founded on.

For education to truly support a future for Indigenous youth outside prison walls, the carceral elements need to be removed from schools. When ideologies of discipline and punishment are used to govern schools, the education system is complicit in the movement of students from classrooms to prisons. Schools must not be places where Aboriginal youth are constructed as unruly and in need of discipline from white saviours. Research conducted by criminologists Raymond Corrado and Irwin Cohen demonstrated that out of 100 Aboriginal youth in custody in British Columbia, 96 per cent of the males and 85 per cent of the females had previously been in trouble at school.

Getting into trouble at school is often the first slip into the “school-to-prison pipeline.” This is a term coined by researchers in the United States, who have been making the links between schooling and prison for several decades. The term describes systemic practices in public schooling such as special education, discipline, and streaming programs that move poor, racialized youth out of school and place them on a pathway to prison.

Prison abolitionist Erica Meiners argues that schools and prisons become interconnected when schools legitimize and enhance select fears that in turn require the intervention of the justice system. This occurs in covert ways, for example, through institutionalized racism, law-and-order approaches to discipline, and the exclusion or negative portrayal of non-dominant groups. Indirectly, these are all processes that can perpetuate fear and encourage discipline and punishment of those students who deviate from the socially constructed and imagined parameters of normalcy.

U.S. education researcher Pedro Noguera points out that racial disparities in school discipline and achievement mirror the disproportionate confinement of racialized people, and that students most frequently targeted for punishment in school often look like smaller versions of the adults most likely to be targeted for incarceration. Noguera further argues: “Schools also punish the neediest children because in many schools there is a fixation with behavior management and social control that outweighs and overrides all other priorities and goals.”

Across Canada, Indigenous students are overrepresented in special education and alternative schooling programs. In 2005, a group of educators concerned about the current system of special education for Aboriginal children organized a national symposium at the First Nations University in Regina. The symposium concluded that the current system of providing special education, “based on the Western views of diagnosis and treatment,” is – simply put – “a mess.”

In British Columbia, one government report notes that Aboriginal students are identified as having severe behavioural disorders 3.5 times as often as the general K-to-12 student population. Teachers, who are predominantly white, frequently have lower expectations for Aboriginal youth than for non-Aboriginal students. Often teachers’ only contact with Aboriginal people is inside their classrooms. The same report notes, unsurprisingly, that Indigenous students report frequent incidents of overt racism in school and often feel lonely and isolated while attending school.

Instead of examining factors like those above, we often turn to paradigms of cultural difference as the explanation and the remedy for Aboriginal under-education. This has been happening since the early 1970s, when government officials began to question why high numbers of Aboriginal students were leaving school. The cultural difference theory has since been repeatedly recycled and usually goes something like this: Aboriginal students are culturally different, and the disconnect between their home lives and school lives is so great that they are unable to succeed in school. More cultural awareness is needed on the part of educators, and more Aboriginal culture must be included in the curriculum.

At first, this theory seems to make sense. After all, schools are Eurocentric, and the infusion of Indigenous worldviews is indeed an important part of decolonizing our schools. Yet the recognition and validation of Indigenous culture is but one part of decolonization. When it is viewed as the solution to everything, taking the form of superficial lessons on song and dance taught by a white teacher, significant change is forestalled. An emphasis on cultural differences also allows for the erasure of topics such as racism, discrimination, and violence. And perhaps most importantly, it allows the blame to remain with the Aboriginal Other, whose “cultural differences” have come to signify inferiority.

Refusing to participate

Many predict that the racial disparity in Canada’s prison population is set to worsen because of the Conservative government’s new crime legislation passed in March. Included in the long list of stiffer penalties composing the omnibus crime bill, otherwise known as the Safe Streets and Communities Act, is the creation of more criminal offences, more mandatory minimums, and the abolition of statutory release with supervision. The legislation has been fiercely opposed by correctional officials, police chiefs, medical associations, victims’ advocates, lawyers, judges, and criminologists, who point out that harsher penalties are ineffective in decreasing crime and that such measures systemically target poor and racialized people.

During the 1990s, when the prison population in the U.S. grew exponentially, school suspensions and expulsions increased drastically as well. Punitive measures in the law-and-order system seeped into schools with devastating consequences for racialized youth. With Canada’s own regressive reforms to criminal laws that shamefully mirror those that have proven to be a failure in the U.S., we must work to resist similar outcomes.

The suggestion that schools place Aboriginal students on a trajectory to prison is in many ways antithetical to democratic ideals of education. But an important part of redirecting the gaze from the colonized to the colonizer is examining what often goes unquestioned or is accepted as common sense. Although schools can be positive forces in the lives of many youth, the opposite holds true for many others.

The over-incarceration of Indigenous people is not an unassailable reality. It is a violent, colonial project that requires the co-operation and complicity of countless people. Unmaking the situation will require the same sustained and concerted effort. Learning how we are all invited to participate in the colonial project of Aboriginal over-incarceration – and then refusing to do so – is the first step in demolishing the pipeline to prison for Aboriginal youth in Canada.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)