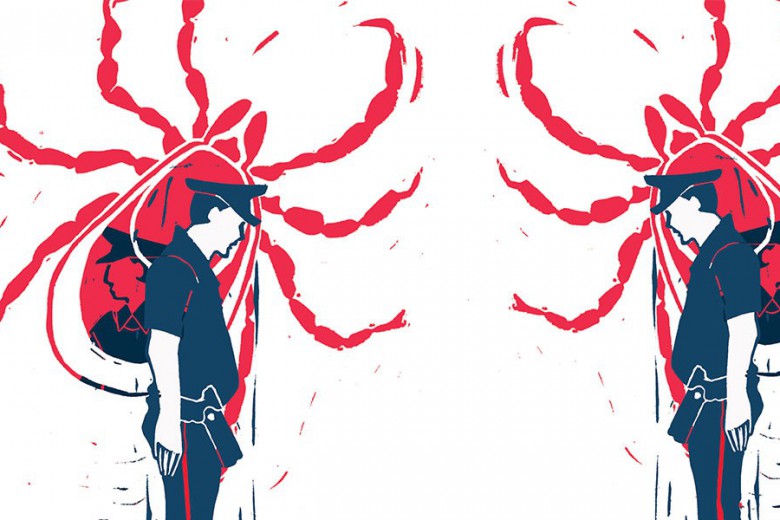

After the uprising for Black Lives in the summer of 2020, I started hearing more stories about Black and racialized students’ experiences with police in their schools. We were not being treated the same as our white peers and having police in school felt unsafe for us.

I was in Grade 10 at Canterbury High School in Ottawa at the time. Canterbury, at least before I graduated in 2022, was not a very diverse school; most students were middle-class white kids. There were no student resource officers (SROs) at the school but every once in a while we’d see a police officer if a student did something supposedly out of line. I felt uncomfortable seeing a police officer walking down the hallway at school.

I was very eager to get involved and do something, and I got word that the Asilu Collective, an organization led by young people committed to driving cops out of schools in Ottawa, was looking for student organizers. I started working with them and some other young people and I was like, okay, let’s see what we can do to make change happen. Here’s the story of how we kicked cops out of our schools and what I’d like to see change in high schools across Canada to be safer for Black students.

Briarpatch: Why did you get involved in the campaign to kick cops out of schools?

I was tired of hearing stories of Black students being targeted at their schools. When my older brother was in middle school, if he was having trouble with another student and they were quarrelling and bothering each other, he would get in trouble but the white kid would not – it seemed like a double standard. At one point, when my brother was around 11 or 12 years old, he did something staff deemed threatening and they brought an armed officer into the school to tell him off. But it was really to intimidate him.

I remember this one Black Muslim girl told me that whenever she saw a cop in the hallway at school, she would feel tense and anxiety would wash over her body like she was waiting for something bad to happen. She would walk past them, and nothing would happen and she would feel relief. But it was that feeling of not being safe.

Even though I hadn’t had a bad experience with police in my school, I could easily see it happening.

I had also heard of a student who was being sexually harassed by another student, and they were told to speak to their school police officers, who were to handle the situation. But the student said they were not listened to, gaslit, and not supported at all.

Those stories really bothered me because even though I hadn’t had a bad experience with police in my school, I could easily see myself in the shoes of these students. No kid should have to deal with that when they’re trying to learn, focus on schoolwork, and simply make it through the day. It was clear to me that SROs were doing more harm than good.

Briarpatch: What was the campaign like? How did the school board react?

We were fighting the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB) a lot. The school board was reviewing the SRO program and members of the public could give their input, so we organized ourselves to show up and collectively advocate for the termination of the program.

We detailed the harmful impacts of the program and policing more widely, and urged them to vote against keeping it. We told them that students needed support, and those supports were not being provided by police, so it was time they got out. A few of the trustees backed us up and echoed the view that cops shouldn’t be in schools in the first place. Some of them actively disagreed with us; they were really preoccupied with this notion of “safety” and what if something bad happened, like a fight. They thought that without SROs, the schools were going to go to shambles. Some of them just nodded and smiled but refused to engage with us.

Black students were not being treated the same as our white peers and having police in school felt unsafe for us.

There was one trustee, a white woman, who was on a board meeting Zoom call and who explained that she initially supported the SRO program because she had heard stories from white kids who said that SROs made them feel safe. But then a Black student told her that he was being victimized by them a lot, and she felt so guilty as she told this story that she started crying, centring herself and her feelings instead of students’ voices. It was a train wreck. The trustees didn’t ask us any questions even though they claimed to value student voices. So mostly, we felt dismissed. But we had to learn to read trustees to understand who was worth our time.

We continued fighting really hard, ignoring the trustees who weren’t interested in listening to students and targeting others we thought we could get on our side. And then on June 25, 2021, they finally decided to discontinue the program. Three days later, Ottawa police ended the entire SRO program for all Ottawa schools because they lost their biggest partner, OCDSB. We were so excited. We had done it.

They have ended the program, but the Ottawa police are still surveilling us. They set up Neighbourhood Resource Teams in 2019 placing cops in community spaces, and in 2021 they expanded the program. So now those officers are policing us in parks and public areas near schools, especially during lunch and after school, when students are likely to be there, supposedly to keep us safe. Officers also still had to be called to schools if a “dangerous” event occurred. So, on paper we won, but they also just kept doing the same things as before. Then, in May 2022, a trustee put forward a motion to reinstate the SRO program. Thankfully it was rejected due to public outcry, but it was very frustrating.

Briarpatch: What resources would you like in school instead of cops?

Counsellors, for one. A lot of my peers in high school were feeling lost. When there’s a violent interaction or something happens, I don’t think that the root of the problem is the violence. I think that it’s just a problem expressing itself. Instead of addressing the larger issues that young people have, we have reactive responses and punishments, and we try to reprimand and scare them into not doing the bad thing again without actually looking into what is going on in this kid’s life. Why are they acting out this way? Are they going through something difficult? Do they have healthy coping mechanisms?

I don’t want to say high school is full of miserable people and all children are miserable, but we kind of are. There was one guidance counsellor at my school and a lot of the students really liked and appreciated talking to her. She wasn’t condescending, and students felt listened to. She was a helpful person for us to turn to. Sometimes the adults we have to turn to, at school or at home, aren’t people you feel comfortable talking to, or sometimes your teachers are rude, or talk down to you, or you don’t feel like you have anywhere to turn. If there were more supports in schools, such as counsellors, mental health supports, and breakfast programs, that would be more effective.

Schools reprimand students without first asking: Why are they acting out this way? Are they going through something difficult? Do they have healthy coping mechanisms?

I remember when a few schools introduced Black graduation coaches and LGBTQ+ counsellors. It’s easier to talk to someone with similar life experiences. If we keep that in mind, and we put people in schools to help students instead of punishing them for how they’re acting, it would really help in the long run. I believe in restorative justice. Some Toronto schools started introducing restorative justice practices, like when two students are in conflict, they mediate a conversation so they can talk through the issue and reach a resolution or compromise instead of just being upset at each other, getting punished, and going about their day until something bad happens again.

We also need people trained in de-escalation. When my brother was younger in school, the teachers and the adults would wait for something bad to happen. They see the students fighting, and they wouldn’t do anything until it escalated. Then they would step in and punish to teach the students a lesson or whatever. That’s the kind of mindset that a lot of people in the school system have but we need teachers and counsellors who know how to talk people down and de-escalate a situation before it gets bad.

Briarpatch: What lessons do you want to share with other students fighting for police-free schools?

Do not lose hope. The campaign definitely became very discouraging. We were talking to people who were ignoring us and it felt like a lost cause and like no good was ever gonna come of our hard work. But showing the school board that students are paying attention to them – we’re not docile, and we stand up for what we believe – is very important.

_1200_675_90_s_c1_.jpg)