No one really knows how many people have been killed by police in Canada in 2018.

There is no federal body in Canada that documents the number of deaths. The names of victims are usually only made public when family members agree to release them, or in the rare instances when charges are laid against officers. And it’s only when charges are laid that officers’ names are released.

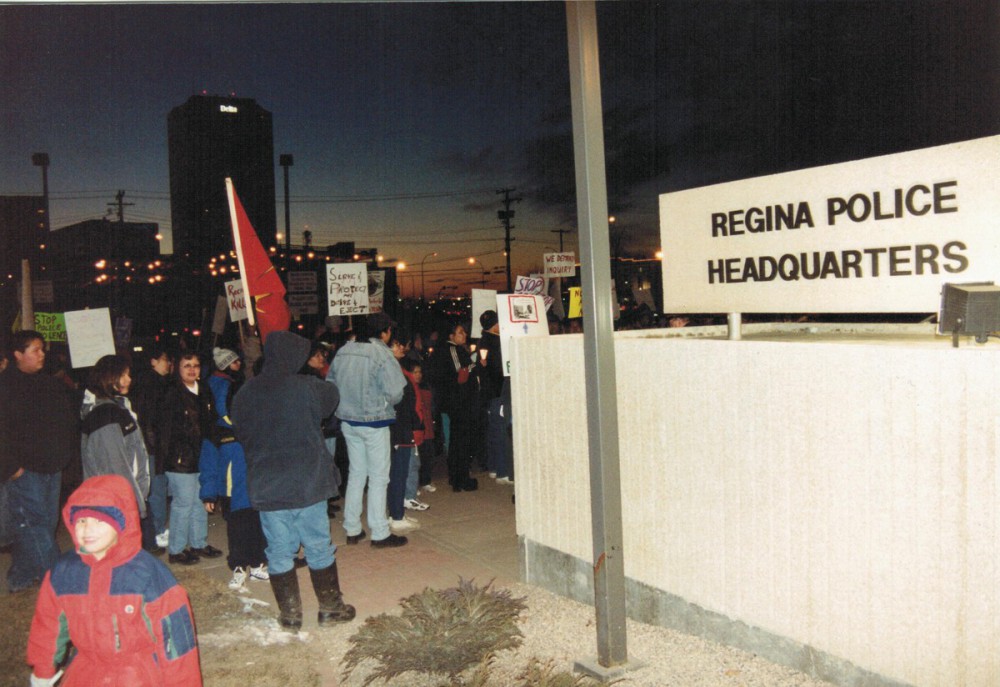

In Canada, anti-police-brutality groups and independent watchdogs often take up the work of documenting fatal police encounters, but these efforts are fragmented by city and province. One of the only national projects dedicated to the task is the blog killercops canada, where I first read about the death of Josephine Pelletier – a 33-year-old Cree and Saulteaux woman who was shot to death by Calgary police in May.

Sometimes journalists will try and track police killings, though coroners’ offices and police departments are increasingly tight-lipped about details of deaths. Travis Lupick at the Georgia Straight, for example, maintains a public database of police-involved deaths in B.C.

It reminds us why we fight against armed officers being stationed in schools, or uniformed cops being allowed to march in Pride parades.

In contrast, in America – where cops kill close to 1,000 people per year, as compared to around 30 per year in Canada – data is collected (however imperfectly) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and the FBI. Officers’ names are usually disclosed, and U.S. media are more practiced at keeping lists of fatal police shootings. For the past four years the Washington Post has been keeping a running tally, with details of each victim’s location, gender, race, age, whether they were experiencing a mental health crisis, and whether they were armed. The Guardian collected these statistics for the U.S. in 2015 and 2016 – and showed that government databases had undercounted the number of victims by half. These journalism efforts began in earnest after 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri put the spotlight on police brutality against Black people in America.

In April, the CBC made an unprecedented effort to map fatal police encounters in Canada. They looked at 461 police-involved deaths between 2000 and 2017, and found that the rate at which Canadians die in encounters with police has nearly doubled in the last 20 years. Unsurprisingly, Indigenous and Black people and people with mental illness are killed at disproportionately high rates. Of the 461 deaths, criminal charges were laid against an officer in 18 cases, and there were only two convictions.

Cops may kill fewer people in Canada, but it’s clear that the same racism and lack of accountability underpins police shootings as in the U.S. The only difference is that, in Canada, it’s accompanied by less transparency and a paucity of data.

Briarpatch doesn’t have the resources to maintain a nationwide database of people who’ve been killed by cops. So we started with one story – the life and death of Josephine Pelletier.

Too often, news articles of fatal police shootings are decontextualized, ripped from history – a Black or Brown person has a mental health crisis, sometimes while holding a knife or wearing a hoodie, and they are shot to death by a cop. The journalist notes whether the victim used substances, or had a criminal record. They take down a few bewildered and mournful quotes from friends and family. Police officers pat themselves on the back at a press conference. The story disappears from the news cycle.

Of the 461 deaths, criminal charges were laid against an officer in 18 cases, and there were only two convictions.

We tried to tell Josephine’s story differently. The author, Sara Birrell, spoke to Indigenous advocates for context, relied on Elders for guidance, and interviewed Josephine’s mother at length. We started at the beginning, with her childhood. We questioned the justice of a system that purported to “rehabilitate” her, but kept her locked in a cage for half of her life. We tried to show that police shootings are almost always precipitated by colonialism, racism, poverty, and stigmatization of mental illness.

It’s important to be able to say the names, and fully tell the stories, of people who have died at the hands of police. It’s only by doing so that we can understand the continuum of police surveillance, harassment, and violence that Black and Brown people live under, which ranges from carding to being killed. It reminds us why we fight against armed officers being stationed in schools, or uniformed cops being allowed to march in Pride parades.

A world without police is a remarkable feat of imagination – because it’s not just about abolishing the police. It’s about envisioning a world in which every person has what is needed to address the root causes of violence and harm, and those resources are collectively provided. That means housing, health care, access to lands and waters that we all protect, and the end of white supremacy and prisons. It means a society based on mutual aid and transformative justice.

It’s a demanding vision, but it’s also a matter of life and death.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)