During the 2018 Ontario elections, a campaign pamphlet for Progressive Conservative (PC) candidate Raymond Cho was distributed with the words “為人民服務” – “Serve the People” – in bold. The phrase is one of the most iconic Maoist slogans – but in this case, it was used as a crude translation of Doug Ford’s slogan, “For the People.”

While the NDP won the majority of downtown Toronto ridings, they were locked out of the suburbs, where the PC Party rode to a decisive victory across the commuter belt of Mississauga, Markham, Etobicoke, and – to a lesser extent – Scarborough.

For some this was unexpected: suburban working-class and immigrant communities might have been expected to side with the Liberals or NDP, more so than the generally whiter and wealthier downtown communities. After all, left-leaning parties are supposed to be the champions of the poor and racialized. For others, election results confirmed a growing belief that Canada’s new wave of immigrants is both socially and fiscally conservative, innately.

We reject these two presumptions. Instead, we draw on the case of Chinese suburbanites in Scarborough and York Region to argue that the electoral success of the right is the result of decades of disengagement by the left and sophisticated politicking by right-wing politicians.

Declawing the left

From the 1970s until fairly recently, it’s been assumed that most older racialized immigrant communities across the country would vote Liberal. One of the key ways in which the Liberals were able to build support, historically, was through the formal and informal connections between social service agencies and party organs.

In Gold Mountain: The Chinese in the New World, Anthony B. Chan explains that a large number of activists within the Chinese community in Canada in the 1970s were social workers who had arrived from Hong Kong and began “champion[ing] the rights of new Asian immigrants, mostly garment workers.” Many of these activists had been politicized through participation in anti-colonial struggles in Hong Kong and inspired by the Cultural Revolution.

One of the key ways in which the Liberals were able to build support, historically, was through the formal and informal connections between social service agencies and party organs.

It was this group of activists who spearheaded a campaign in response to television network CTV’s racist depiction of Chinese students in a 1979 W5 episode, which argued that Chinese students were stealing university spots from white Canadians. These activists criticized the representation of Chinese people as inherently foreign, and successfully challenged CTV by organizing protests across the country.

However, in 1981, Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government, fearing the disruptive potential of a grassroots Chinese-Canadian political movement, sought to stifle it by providing an operating grant to the Chinese Canadian National Council for Equality (CCNCE), the organization born from that grassroots movement. This funding smothered “the possibility that the CCNCE might direct political dissent toward the government,” writes Chan. The “final symbol of co-optation” happened in 1981, when the CCNCE dropped “For Equality” from its name.

This is consistent with analysis produced by INCITE!, a network of radical feminists of colour, who argue that the non-profit sector’s emergence across North America declawed mass social movements of the 1960s and 1970s by folding them into the structure of the state.

In the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), organizations like the Hong Fook Mental Health Association and Chinese Family Services of Ontario serve the Chinese community. They provide health services, migrant support services, shelters, and more – but they operate under laws that would strip them of charitable status or funding if they don’t limit their political and partisan activities. While aspects of the non-profit social service sector were very much the product of political struggle, its rise also meant that energy and funds were diverted from radical leftist grassroots activism to the state-sanctioned non-profit industry.

The “final symbol of co-optation” happened in 1981, when the CCNCE dropped “For Equality” from its name.

The model of “service without organizing” – of providing support without talking about how issues like homelessness, poverty, and domestic violence are structurally reproduced – is ultimately a recipe for disaster. It perpetuates the power of middle-class brokers, and fails to politicize new migrants. As a result, beginning in the 1980s, there was a political vacuum in the Chinese community where the grassroots left used to be, which the right has been only too happy to fill.

The reactionary trinity: churches, media, and the PC Party

In February of 2015, the minister of education, Liz Sandals, introduced an updated sex education curriculum to be taught in Ontario grade schools – one that included discussions of LGBTQ identities, sexting, cyberbullying, and consent. Immediately, a populist movement opposing the changes reared its head. The movement successfully linked white social conservatives with religious fundamentalists in various racialized communities, including Chinese communities.

Chinese Christian churches, Chinese-language media, and the ways each are intertwined with the PC Party have played a major role in this movement. Immigrant churches are places where trust and mutual understanding are established through sharing cultural practices and language, as well as common hardships, job insecurity, language learning, and feeling uprooted. The material and social supports that churches offer draw Chinese newcomers in, but few of their experiences of economic marginalization find meaningful solutions there.

Those who take up leadership positions within these churches are often middle-class professionals and business owners. Instead of discussions of economic justice, which would appeal to working-class churchgoers and newcomers, issues that take the forefront reflect the desire of the church to maintain certain social and moral norms. From decrying Islam to panicking about the evils of sexual liberalization (regarding homosexuality, sexual education, and abortion, among other matters), many Chinese Christian churches have come to align themselves with values of the right.

The material and social supports that churches offer draw Chinese newcomers in, but few of their experiences of economic marginalization find meaningful solutions there.

At Scarborough Chinese Alliance Church, for example, the church’s social networks and volunteer base have become recruiting grounds for campaigns against “moral devolution.” Volunteers recruited within the church staff information booths in the church lobby, and distribute informational leaflets and petitions to reverse the sex ed update. In 2018, the election of a number of prominent Chinese PC Party members to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario – such as Billy Pang, a pastor, and Daisy Wai, a senior church leader and business lobbyist – show how Chinese churches, the PC Party, and class power are intertwined.

Right-wing operatives also leveraged traditional media (print, radio, and television) and social media to spread their claims. In terms of traditional media, Fairchild is the dominant Chinese-language broadcaster in Canada, and is uncontested by left-wing alternatives. Fairchild’s monopolization of the Chinese-language market can be traced to its purchase of a competing Chinese-language media outlet, Chinavision, in 1993. Before that, in 1987, Chinavision had bought its competitor, Cathay International Television. In radio, Fairchild Media Group owns and operates Fairchild Radio (CHKT), but also produces content for CHIN and CIRV. Television and radio shows on these networks, as well as print media, have often provided a platform for opponents of the sex ed curriculum. It was through this platform that right-wing activists were able to spread ideas that the curriculum promoted anal sex, alongside transphobic and homophobic critiques about the inclusion of gender and sexual diversity topics in the curriculum.

As for social media, a number of groups formed on Facebook and WeChat (the major social media platform used by Chinese speakers), including the Parents’ Alliance of Ontario, Parents as First Educators, and the Coalition of Concerned Parents. Here, Chinese right-wing activists found their voice, reaching and galvanizing thousands. This online support translated into real-life rallies and protests, including an incident where protesters disrupted an information session on the curriculum changes held by MPPs in Scarborough. The election of Doug Ford was an indisputable victory for the anti-sex ed campaign. Within a month of taking office Ford scrapped the curriculum changes.

Hijab-cutting incident

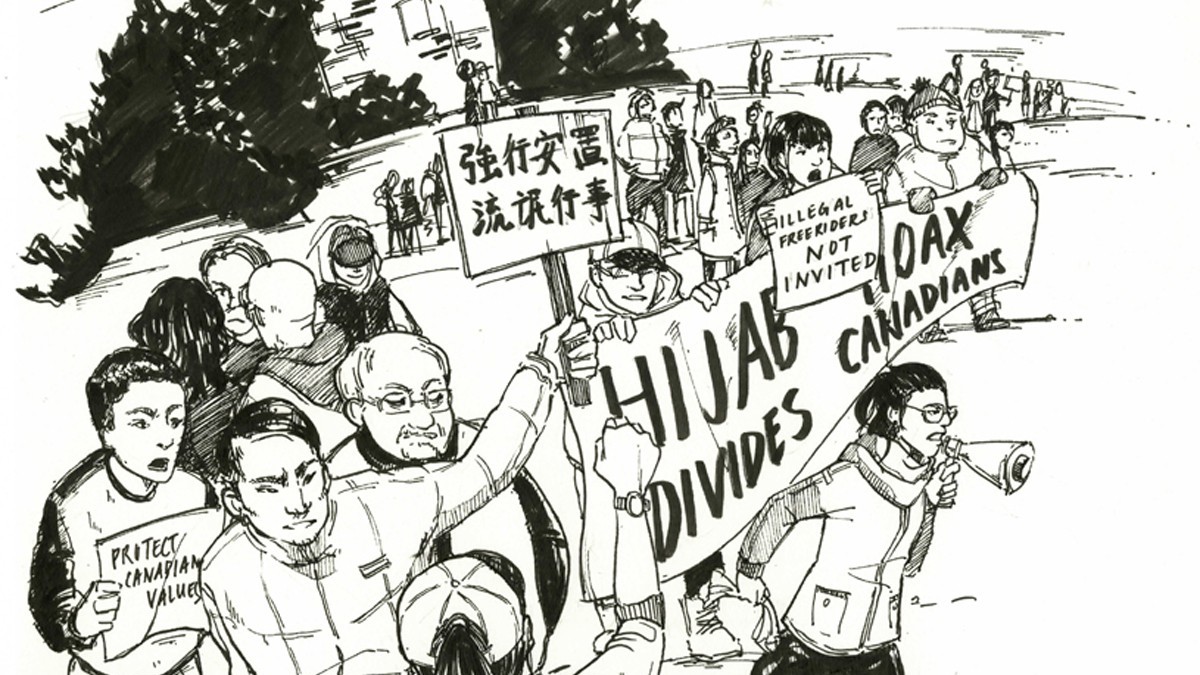

The networks formed within the Chinese communities through the anti-sex education campaign soon found political opportunity in attacking Muslim communities. On January 28, 2018 – the eve of the first anniversary of the Quebec mosque massacre – a few prominent organizers of the anti-sex ed campaign coordinated countrywide protests in relation to an incident where an 11-year-old girl had accused an East Asian man of cutting her hijab on her way to school. This accusation later turned out to be false, but only after political leaders like Justin Trudeau and Kathleen Wynne spoke out against the alleged incident. It became a lightning rod for nationwide backlash that culminated in a rally on Parliament Hill, attended by white supremacist groups like La Meute.

The appeal of Islamophobia – particularly the portrayal of Islam as a threat to “Western civilization” and Chinese communities alike – is amplified by the fact that it is often couched in language that speaks to genuine concerns about anti-Chinese racism and marginalization. Examples of this language include slogans like “All Canadians are Equal.” Jenny Wong, a participant in the protests, told People’s Daily Online that “it is definitely a humiliation to [the] Asian community, which has always been picked on. Even an 11-year-old knows that we are easy targets.” By conflating this incident with day-to-day experiences of anti-Chinese racism, right-wing activists portrayed this campaign as a fight to restore dignity for a community targeted by Muslims and the state. But this backlash can also be tied to the PC Party’s opportunistic desire to discredit Liberals, with little concern for the resultant fractures between ethnic communities. The role of political opportunism is particularly obvious when looking at the number of signs brought to these events that explicitly targeted Trudeau and the Liberal Party.

It became a lightning rod for nationwide backlash that culminated in a rally on Parliament Hill, attended by white supremacist groups like La Meute.

Right-wing and PC operatives had effectively tapped into the racism that Chinese immigrants face, and weaponized it against Muslims and the Liberal government. An attendee at a so-called “Hijab Hoax” rally tells us, “Do you know how much racism I face at work from customers and the police? Of course, when Chinese people finally stand up for our rights, I am going to go out there.” Protesters were drawn to what they understood as a challenge to anti-Chinese racism – a challenge rarely mobilized and articulated – that resonated with their own experiences of racism. And with the lack of leftist engagement in these communities, political actions like the “Hijab Hoax” campaign become an attractive outlet for Chinese frustration with racism. Despite the campaign’s failure to address the systemic roots of anti-Chinese racism or to account for the compounded prejudices that Muslims face, it is now the right wing that is seen as the main defender of Chinese communities against racism.

Anti-refugee protests in Markham

In late July 2018, a rally was organized in opposition to a proposal by Frank Scarpitti, the mayor of Markham, to house asylum seekers in the city. A rally call-out and petition distributed through social media even fabricated a claim that Scarpitti had planned to resettle 5,000 asylum seekers in Markham. The initial call-out and petition also referenced the fact that 70 per cent of asylum seekers who arrived through irregular border crossings were Nigerian – making it obvious that the mobilization was fuelled by anti-Black racism, in addition to Islamophobic and anti-refugee sentiments.

At the rally, organizers again relied on fake news, with speeches blaming refugees for the recent mass shooting on the Danforth that killed three people and injured 13 more. A mother claimed that she feared for the safety of her children, in light of asylum seekers potentially living in the neighbourhood. Others complained about having their taxes spent on supporting “freeloading” foreigners.

Further investigation revealed that many of the organizers had ties to the PC Party or were political hopefuls with an eye on the upcoming municipal elections. For example, Shan Hua Lu, a Markham mayoral candidate at the time, and Charles Jiang, a former Progressive Conservative nominee hopeful and Markham city councillor candidate, helped organize the rally and were responsible for delivering the petition to city hall in the days following. A source within the PC Party also told us that the rally was an attempt to sully Scarpitti’s name, as established PC candidates feared that Scarpitti would run in the upcoming federal elections. Instead of drawing parallels between shared struggles of migration, state supports for asylum seekers – themselves falsely portrayed as uniformly Black or Brown – were portrayed as another example of the government’s failure to address experiences of marginalization faced by Chinese migrants.

Fighting the right, building the left

The latest obsession with wealthy Chinese immigrants buying vast swathes of expensive real estate in Canada represents the racialization of growing income inequality. In actuality, a review of the community reveals a much more complex class landscape.

The Chinese diaspora is itself tremendously fragmented along class lines and marked by significant disparities in income. Between 2011 and 2016 the number of Chinese migrants admitted to Canada through business programs (entrepreneurs, investors, and those who are self-employed) was less than a fifth of the total number of Chinese migrants admitted. Family migrants and non-investor migrants (including refugees), who are typically far less wealthy than investor migrants, often labour in blue-collar jobs without the protections that unionized work may have for many blue-collar workers in white communities.

These populations provide a natural base for political campaigns based on left-wing agendas, but they remain unmobilized. Another sizable segment is skilled workers who experience immediate deskilling and downward mobility upon entering Canadian labour markets. The racist deskilling they face should be addressed and harnessed by the left as an opportune moment to politicize new migrants.

State supports for asylum seekers – themselves falsely portrayed as uniformly Black or Brown – were portrayed as another example of the government’s failure to address experiences of marginalization faced by Chinese migrants.

By being barred from white and English-speaking labour markets, deskilled workers, undocumented workers, and migrants who don’t speak English are often forced into industries and sectors where regulations are weak and worker protections are low. Take, for example, the issue of wage theft: in a 2016 survey of 184 Chinese restaurant workers in the GTA, 43 per cent reported being paid below minimum wage. In one widely publicized incident, it was found that Regal Restaurants had stolen wages totalling more than $650,000 from over 60 Chinese restaurant workers in the GTA.

It is precisely the working-class and deskilled immigrant experiences that the right wing operatives have tapped into, asking loaded questions like, “Is it fair that you worked so hard through all those poor jobs, just to pay taxes to support these ‘fake’ and morally questionable refugees?” These ideologies, when unopposed, move working-class people away from developing class consciousness and identifying their true oppressors.

Sadly, the left has often been uninvested in the struggles of Chinese and other racialized working-class immigrants. Some NDP campaigners told us they were instructed to avoid canvassing in Chinese communities in the lead-up to the recent elections, as it was assumed that Chinese Canadians would not be interested in left-wing demands. Based on these racialized assumptions, one NDP canvasser told us they expected “people to slam their doors in my face.” Instead, the canvasser discovered that when they actually spoke to residents in their language, “most [residents] found the NDP’s policies agreeable.” It was the lack of sustained political education, organizational power, and leftist Chinese media long before the 2018 election that ultimately meant many of these neighbourhoods voted for Progressive Conservatives.

The issues that many Chinese community members face – like xenophobic racism, poor working conditions, and growing economic precarity – could be used by the left to galvanize the community into standing in solidarity with other marginalized communities and demanding a more just society for all. Building institutional power and movements across communities to do this (like the Fight for $15 and Fairness) will be essential to these efforts. In their absence, the right has managed to take over all the important sites of community power: churches, non-profits, and media. In short, it is precisely the left’s inability to mobilize upon class issues most relevant and related to racialized suburban communities that has given the right and the Conservative Party free rein in those communities.

The electoral success of the Progressive Conservatives and the rise of far-right elements in the community should serve as a wake-up call for additional work on the political landscape across not only Chinese suburban communities but throughout immigrant suburban communities more generally. More importantly, it should serve to galvanize renewed community organizing work that builds solidarity within and across racialized communities, and addresses the very real economic and social concerns held by members of these communities. For communities that face economic precarity and social marginalization, solidarity is the key to changing the landscape of power in Ontario.

_copy_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)