Mass temporary migration is the new global normal. In 2019-2020, over 3.4 million new temporary permits were issued in the United States. In Canada, at least 870,845 new temporary study, work, and refugee permits were issued in 2019, more than 2.5 times the number of permits issued for permanent residency. Similar ratios of temporary permits are being issued annually in Australia, the U.K., and South Africa. In the Persian Gulf countries, the ratio is much higher.

And as large as the number of new permits is, it belies the actual scale. Many migrants are issued multi-year temporary permits in most countries, but after they’re issued, permits are rarely tracked. Around the world, millions are undocumented and do not feature in statistics. In Canada, at least 1.6 million people, or one in 23 people in Canada, don’t have permanent resident status. Here, I refer to all of them as migrants.

The number of merely temporary work permits in Canada ballooned by 615 per cent between 2000 and 2018. This rapid expansion of temporary migration is new. It is being organized and coordinated globally through organizations like the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and championed at places like the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD). Met with little of the analysis and criticism that their older siblings – the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Economic Forum – receive, the IOM, the GFMD and others like them have created a global consensus in favour of temporary migration. Their main arguments would be laughable were it not for their wide-ranging acceptance. For example, the GFMD has proposed that the money that migrant workers send to their families in the Global South can be a replacement for financial aid from the Global North to the Global South, essentially positing the denial of citizenship rights as a benevolent mechanism to support poorer countries. Understanding the specifics of this discourse and its deployment is essential for anyone serious about ending capitalism and building a more just world.

Therefore, the struggle for migrant justice is not just for the “right to stay” but for all civil, political, labour, and economic rights from which migrants are excluded when they are deemed “temporary” or made undocumented.

It is important also to note that lack of permanent resident status doesn’t just bar a migrant from staying in a country. In fact, hundreds of thousands of migrants spend the majority of their lives in countries where they don’t have immigration or citizenship status. Rather, temporary or undocumented status means that a person is excluded from basic labour protections, health care, education, and other social services while being separated from their families by immigration laws that bar sponsorship.

Therefore, the struggle for migrant justice (including the campaign for Full and Permanent Immigration Status for All) is not just for the “right to stay” but for all civil, political, labour, and economic rights from which migrants are excluded when they are deemed “temporary” or made undocumented. Arguments about migration that frame the question as if it is about total number of “immigrants” versus “migrants” fundamentally misrepresent the long-term nature of temporariness.

The issue isn’t just the exclusion of migrants; these hard-fought and hard-won rights and freedoms are being eroded for everyone else, too. That is, as “universal” protections (like health care and labour laws) are denied to one group of people, it opens up the possibility of them being denied to others.

Migrant? Refugee? Student? Undocumented?

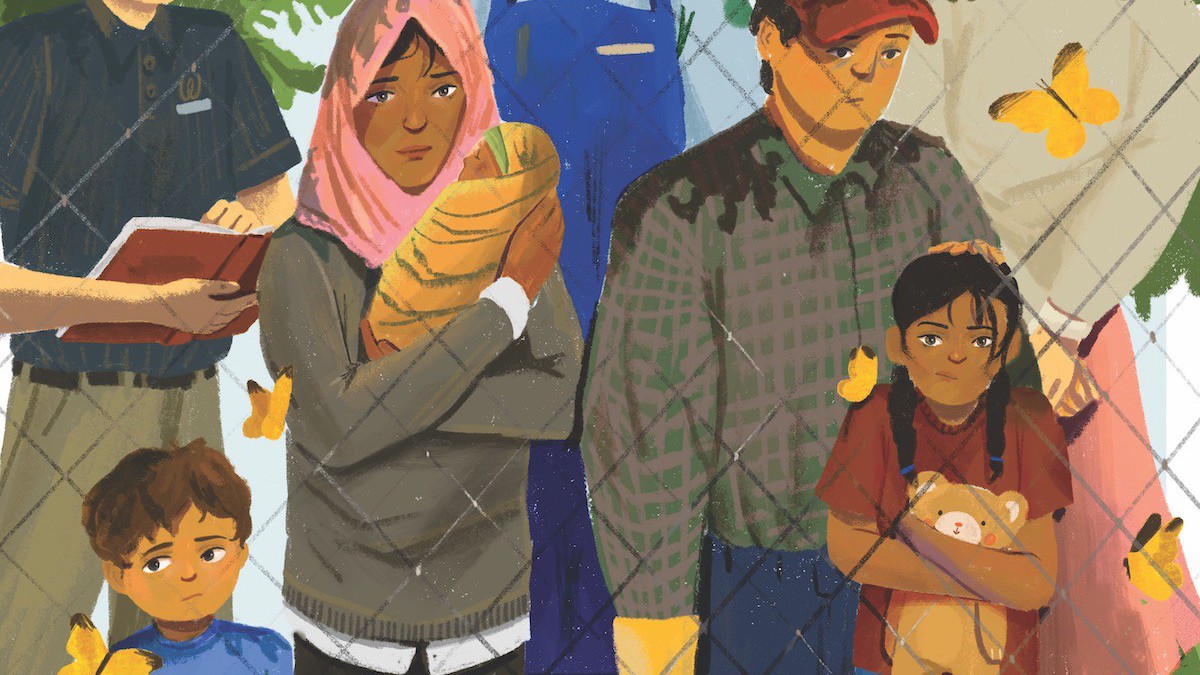

When speaking of migrants, one of the dominant notions is that their experiences vary widely based on their reasons for migration and the legal category they are sorted into by the countries to which they migrate. This idea sows competition and conflict between those deemed deserving of our compassion (the refugee) and those who aren’t (the economic migrant), or those who add value (the highly skilled worker or student) and those who don’t (the border crosser or the low-wage worker). Proposed solutions are also shaped by this idea of different categories of migrants. For example, in 2020, the federal government of Canada created a program that gave refugee claimants in limited occupations in health care access to permanent residency, as a “gift” to these “guardian angels.” The underlying argument was that they are refugees (making them deserving of compassion) and engaged in essential work (making them guardians). This separated the “angels” from all other migrants who want and deserve access to the basic rights and services that come with permanent residency.

More importantly, this divided framework accepts state-determined categories that are and always have been technologies of control.

It’s time to move beyond the “reasons for migration” question as a totalizing framework. It’s impossible to determine individual motivations, and even if it were, migrants can have more than one motivation (a person fleeing a war zone may also be looking for a better job). More importantly, this divided framework accepts state-determined categories that are and always have been technologies of control. Such division also centres individual migrant intentions rather than examining the conditions that force them to move (war, climate change, economic collapse) – and it seeks to obfuscate the Western or Global North complicity in creating those conditions.

Instead, it is crucial to understand and assert that the laws in migrants’ arrival countries determine the conditions of each migrant’s life. These laws treat migrants collectively – through exclusion – as much as they treat them as distinct and separate categories. As a result, migrants have a shared universalizable experience that can both propel collective action for social transformation and be used by the richest few to pit migrants against local residents, particularly low-waged and poor people.

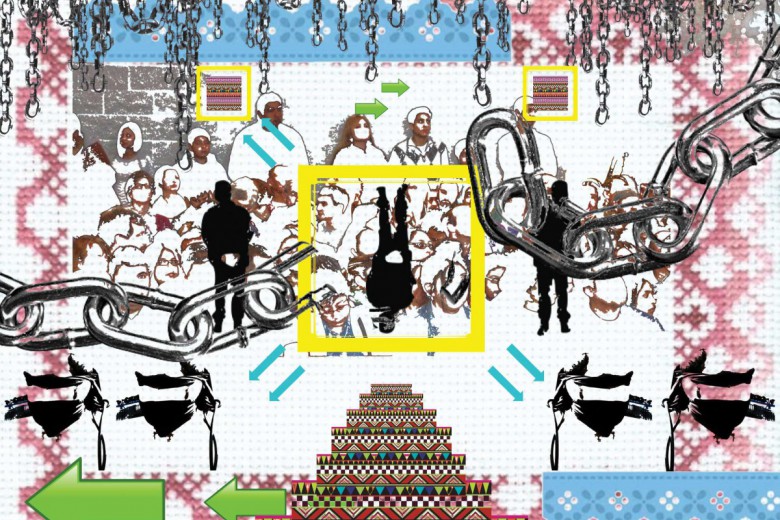

Forging unity as migrants, particularly as working-class migrants, is not about eliding difference. Rather, it is about joining links into a chain strong enough to pull down capitalism and racism and equitably redistribute wealth and power. The type of permit issued will determine differences in access to services and rights, while experiences will vary according to wealth, gender, racialization (including those who are Black and those who are not), language and literacy levels, country of citizenship, rural or urban proximity, disability, sexuality, and more. Keeping these differences in mind, consider the various categories into which the Canadian state sorts migrants and the ways in which they face a common structure of racialized and gendered exploitation and exclusion:

Refugee claimants

(also known as asylum seekers)

63,830 in 2019

Most refugees are employed under open-work permits. These permits place no restrictions on hours of work, employer, or sector except for prohibiting “businesses related to sex trade.” These jobs are typically poorly paid – often in cash – and labour exploitation and racism are common. Refugees receive access to health care and social services when they first apply, but these services are quickly revoked after the first time their claim is denied, even if an appeal is under way. Many continue to work as they await a final decision, essentially as if they are undocumented. Anti-refugee sentiment is often mobilized to drum up support for austerity. Refugees are blamed for taking up beds in homeless shelters or for receiving benefits needed for other poor and disadvantaged people.

Temporary foreign workers on closed permits

(agricultural workers, care workers, etc.)

56,850 agricultural workers; 7,670 care workers; 42,175 in other industries in 2019

Closed-work permits only allow migrants to work for the employer or in the sector named on their permit. Some permits are seasonal and allow workers to stay in the country for a maximum of eight months – this is common for migrants working in Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program. Most other permits last for one or two years. Changing jobs is difficult at best and impossible at worst, making it untenable for workers to assert the few labour rights they do have. Access to health care exists to varying degrees – it tends to be minimal, if it exists at all – but public education and family unity are effectively prohibited. While the government promises a “path to permanent residency,” it’s less of a path than it is a minefield. For example, seasonal farmworkers must first transition into and hold a full-time job for a year – which includes changing their immigration permits – pass a language test, and have their education accredited before even being eligible to apply for permanent residency. Migrant care workers must also work for two years, pass difficult English tests, and have their education accredited. These hoops aren’t just difficult to jump through; they are mechanisms that employers use to hold workers hostage. Workers are excluded from rights not specifically on the basis of immigration status, but because they are workers in industries that predominantly employ migrants. For example, agricultural workers are excluded from overtime pay, minimum wage, and breaks in many provinces, and in places like Ontario in-home domestic workers are excluded from workplace health and safety protections. Changing jobs or renewing permits is difficult and as a result, many become undocumented.

Study permit holders

638,960 in 2019

While some study permit holders are wealthy, many more are working in low-waged jobs. A significant number study in private institutions or language schools, and after perfunctory classes sometimes lasting just a week, they begin to work in what are often low-wage, cash jobs. Only those in government-approved designated learning institutions (which are mostly public institutions) are allowed to work off campus, so those in most private institutions are effectively engaged in undocumented work, facing labour exploitation, and fearing detention and deportation. Those who meet the stringent requirements for off-campus work are generally allowed to work 20 hours weekly off campus during the semester, but as most shifts are seven to eight hours, taking just three shifts a week means exceeding the 20-hour limit and risking detention and deportation. Employers know as much and use the fact of “law-breaking” as a way to pay workers less, discriminate against them, and force them into more dangerous and difficult conditions. Health care is privatized, and social supports such as public housing and social assistance are prohibited. While spouses can accompany some study permit holders, fees are high and supports are minimal. Failing school can mean becoming undocumented.

International Mobility Program (IMP)

441,825 in 2019, approximately 150,000 of which are post-graduate work permit holders

With nearly half a million people in the program working in various occupations and industries, a number of different rules apply. Generally speaking, IMP workers are on open-work permits (meaning they have no restrictions on hours of work, employer, or sector except for prohibiting “businesses related to sex trade” ). Generally, they must have work permits lasting over six months, and in some provinces they must work full time for over six months, to access health care. Many other social services, including post secondary education, are not accessible to many. Permit holders must also complete at least 12 months of highly skilled work to be eligible to apply for permanent residency (some, however, are still excluded from applying). As a result, they must rely on employers to issue letters confirming their employment in order to be able to stay in Canada permanently and reunite with their families. Labour abuse is therefore common, with employers exploiting workers in return for such letters. Racism and discrimination mean that thousands aren’t able to find jobs deemed “high-skilled,” and they eventually become undocumented or are forced to leave Canada. In January, post-graduate open-work permit holders campaigned to make their permits renewable, and over 52,000 people now have a one-time chance to extend their permits.

Undocumented

Approximately 500,000 in 2019

Most migrants issued temporary permits in the streams outlined previously are eventually forced to make a stark choice: leave the country or stay without being able to renew their permits. If they choose the latter, they become undocumented. Undocumented workers continue to work, facing low wages, discrimination, and the constant fear of detention and deportation. Health care, education, and income supports such as employment insurance, social assistance, the COVID-19 Canada Recovery Benefit, and other social services are out of reach – even during a pandemic. Undocumented workers can apply for permanent residency through humanitarian and compassionate applications, but applications are difficult and expensive and acceptance rates are incredibly low. As more people enter the country on temporary permits, more will be made undocumented.

Migrant: A revolutionary subject

Refugees, students, closed- or open-work permit holders, and undocumented people are often framed as separate groups, but they are in fact collectively exploited in racist and gendered ways, particularly those in low-waged work deemed “low-skilled.” Where they have a path to stability through access to permanent residency, they must pass ableist health exams and fulfill difficult criteria. Together, they are excluded from rights and benefits through an interlocking set of Canadian federal, provincial, and municipal laws and policies, as outlined above. This is not a result of oversight, lack of understanding, or misinformation in policy making. Migrant exploitation is collective and by design.

In our current economic system, capitalism, the rich get richer by exploiting worker power. To do so, bosses ensure that workers know they are replaceable by another, even more poorly paid worker. For this threat of replacement to be effective, social support systems must be made weak enough to make even a brief period of unemployment untenable.

This is not a result of oversight, lack of understanding, or misinformation in policy making. Migrant exploitation is collective and by design.

Until the first part of the 20th century in North America and Europe, the local labour force faced labour exploitation, while hyper-exploitation was carried out against indentured workers and enslaved people. At the same time, colonialism allowed for workers and resources to be stolen from around the world. With the growth of anti-colonial struggles, particularly following the Second World War, and the strengthening of labour unions in the inter-war and post–Second World War period, capitalists saw their ability to hyper-exploit workers lessen as a direct result of collective pushback. It is in this period that temporary migration schemes begin to be created: in Canada, the West Indian Domestic Scheme was created in 1955 for Black West Indian women, the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program in 1966 first for Black Jamaican workers, and the Non-Immigrant Employment Authorization Program (NIEAP) in 1973.

These temporary migration schemes were created as neoliberal economic policies were being imposed both in the Global North and the Global South. These policies aimed to lessen the power of workers and unions in the North and South as well as drastically privatize public services. But neoliberal policies faced a roadblock. Workers cannot be underpaid to such an extent that they are unable to consume capitalist products. Temporary migration schemes exist as a solution to the tension between the competing capitalist desires and requirements to simultaneously underpay workers while still requiring them to consume goods.

As a result, temporary migration is being expanded both as a mechanism to undercut local worker power and to satisfy the never-ending drive for profit by creating a subclass of workers who can be exploited and excluded differently. It’s also used to deflect anger at austerity policies by blaming migrants for driving down wages and working conditions and overusing social services. The racist, nationalist project of blaming immigrants for the impoverishment of other workers works hand in glove with the interests of the richest few. It is part of the global effort to fragment production and allow capitalists to exploit workers far from their shores.

As people in the Global North get older and have fewer children, capitalists require a steady stream of workers to ensure that industries keep running and services keep being provided. In this moment of late-stage capitalism, immigrants and migrants (that is, those with marginal rights and those without rights) are necessary for societies in the Global North to reproduce themselves.

As a result, temporary migration is being expanded both as a mechanism to undercut local worker power and to satisfy the never-ending drive for profit by creating a subclass of workers who can be exploited and excluded differently.

Giving everyone immigration status and full rights on arrival would be easy but less profitable. To avoid doing so, governments have created the category of “migrant” as one who can be denied services. The creation of this category has required upending structures in public services, planning, and policy. Just in the last two decades, most of our society has been re-engineered to respond to and exclude migrants. But public planning discussions around these issues pay minimal or no attention to how temporary migration is shaping outcomes. For example, health care has been redesigned so that a health card is required to access it, excluding all those who don’t have such a card (which is, by my calculation, hundreds of thousands of people in Canada at any given time). Similarly, through inventing the category of “study permit holder,” so-called public educational institutions are permitted to charge some students three times more for the same education, to make up for government funding shortfalls and profit-making administrative models. Policing, prisons, immigration enforcement, and surveillance technologies to control and mediate migrants have ballooned and are used to maintain the fear and practice of incarceration and exclusion. The Canada Border Services Agency and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the U.S. were both created after September 2001. Immigration laws that take away permanent residency from migrants have been created, and vast databases that integrate U.S. and Canadian border controls have been set up. The exclusion of migrants has also been built into housing, real estate, banking, and finance.

While at least one in 23 residents of Canada are migrants, they make up an even larger section of the workforce. It is not, as some have said, that “migrants do work that locals won’t do at the same pay,” it is that work (and corporate profit expectations) has been fundamentally transformed and expanded to require extreme exploitation. Canada, for example, is the world’s fifth largest exporter and importer of agricultural products. The entire global food supply chain requires migrant food- and farmworker hyper-exploitation and abuse in Canada. It is not a question of Canadians “choosing” to refuse work at “low pay.” Instead, global employment practices have shifted to demand exploitation through the use of immigration laws in most countries in the Global North.

At the same time, responses from Canada’s left lag behind. Most private-sector unions can count migrants as members or as prospective members in the workplaces they wish to unionize. Yet instead of actively organizing working-class migrants, some labour unions have taken positions against migrant workers. Social and environmental movement organizations treat migrants as one of many issues, rather than treating temporary migration schemes as a mechanism through which all other systems are being restructured. Where there are campaigns or calls for support, they approach migrants as people who are being exploited – and who deserve support or charity – because of their positions within separate categories.

Forging unity as migrants, particularly as working-class migrants, is not about eliding difference. Rather, it is about joining links into a chain strong enough to pull down capitalism and racism and equitably redistribute wealth and power.

Migrants are revolutionary subjects, not objects of charity. Working-class migrants are now a central part of the local working class in virtually every town and city. Many migrants work in “essential industries” – that is, industries like agriculture and health care, without which society and capitalism cannot function. While doing so would be incredibly difficult, migrants can withdraw their labour from these industries and bring them to a grinding halt. And migrants are engaged in struggle. In 2020, as in previous years, migrants have fought for economic rights, labour rights, and access to services. And as with any other process of organizing, migrants are conscientizing, gaining a critical awareness of the forces which shape their reality. In Canada, much of this work is being coordinated by migrant-led groups in the Migrant Rights Network coalition – one of the few ongoing campaigns of cross-country organizing with a focus on building worker power. This political organization makes it possible (though the work is far from uniform) to support the transformation of economic fights into political ones. By virtue of members’ ties to their home countries, the outlook of members is necessarily internationalist.

Today, power is concentrated in the hands of the few – particularly in Canada, where settler-colonialism continues to this day. It is those same hands that hold onto the land and that have created the conditions of temporariness. The political task, then, is to be engaged in collective struggle, alongside masses of working-class people. In that process, we transform ourselves toward revolutionary practice that will redistribute wealth and power and ensure dignity for those of us made wretched. It involves not just those who have self-selected into struggle, but also entire communities that are permanently organized. The road to liberation is long and must be built anew by each generation. It cannot be done without migrants.

_copy_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)