The past year was difficult, fraught with virulent culture wars, white supremacy, and rising conservatism. It felt like society was returning to darker times while being flung into a frightening future. In the last few months of 2017 I sought refuge in art, unplugging my phone and revelling in the calm of the gallery.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery’s (WAG) current exhibition, INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE, has been part of my solace. Curated by Julie Nagam and Jaimie Isaac, INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE features the work of 29 artists. Spanning over 17,000 square feet, it is the largest contemporary Indigenous art exhibition in the WAG’s history. The show is framed as an act of rebellion and a revitalization of Indigenous culture that challenges dominant Western methods of artmaking and presentation. There are site-specific pieces, debuts, commissions, and a range of media presented, from video and sound to moose tufting and beadwork, all created by Indigenous artists from communities across the country.

The exhibit begins for me with Kenneth Lavallee’s Creation Story (2017), a giant vinyl banner installed on the gallery’s Tyndall stone exterior. Lavallee’s undulating, stylized waves rendered in rich blues and greens contrast with and soften the hard, minimalist lines of the building’s façade and inject colour into the downtown’s grey landscape. Creation Story is one of eight pieces displayed outside WAG’s designated exhibition spaces, reflecting the show’s mission to subvert traditional gallery practices and engage the public.

The first piece upon entering the building, Kent Monkman’s Death of the Female (2014), is a virtuosic “Old Masters”-style painting depicting a violated Cubist female figure surrounded by a group of men in front of a dilapidated house in Winnipeg’s North End. The woman’s bag and its contents lie scattered a few feet from her, while the perpetrator, a hulking bull, symbol of virile masculinity, flees the scene in a muscle car. Monkman often uses aggressively flattened female forms to signify how modern male artists exploit the female body, rendering it motionless and without agency. The violence inflicted upon the female form also addresses the devastating reality of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

From Monkman’s piece, the eye is drawn upward to Hannah Claus’ cloudscape (2012), a soaring installation that softens the cavernous hall with small white circles suspended on threads. The material’s simplicity belies the dazzling effect of the shapes floating in open space. The Skylight Gallery is transformed by Casey Koyczan’s Gone But Not Forgotten (2017), made of suspended driftwood found on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. The piece hangs in memory of missing Indigenous peoples who have disappeared in Winnipeg’s waters.

Many works in the galleries blend traditional Indigenous materials with technological innovations. Couzyn Van Heuvelen’s series of fishing and hunting implements are replete with miniature animal skulls crafted from baleen and muskox horn using a 3D scanner. Tsema Igharas’ Ejinda – Push it! (2017) is an amplified, stretched caribou hide that viewers are invited to touch. It creates booming sounds when struck, rupturing the sacrosanct hush that often stifles the gallery, itself a decolonizing act. Additionally, Tanya Lukin Linklater’s The Treaty Is In The Body and the Earthline Tattoo Collective’s mobile tattoo parlour have interactive elements and destabilize traditional gallery restrictions on touching, playing, and making noise.

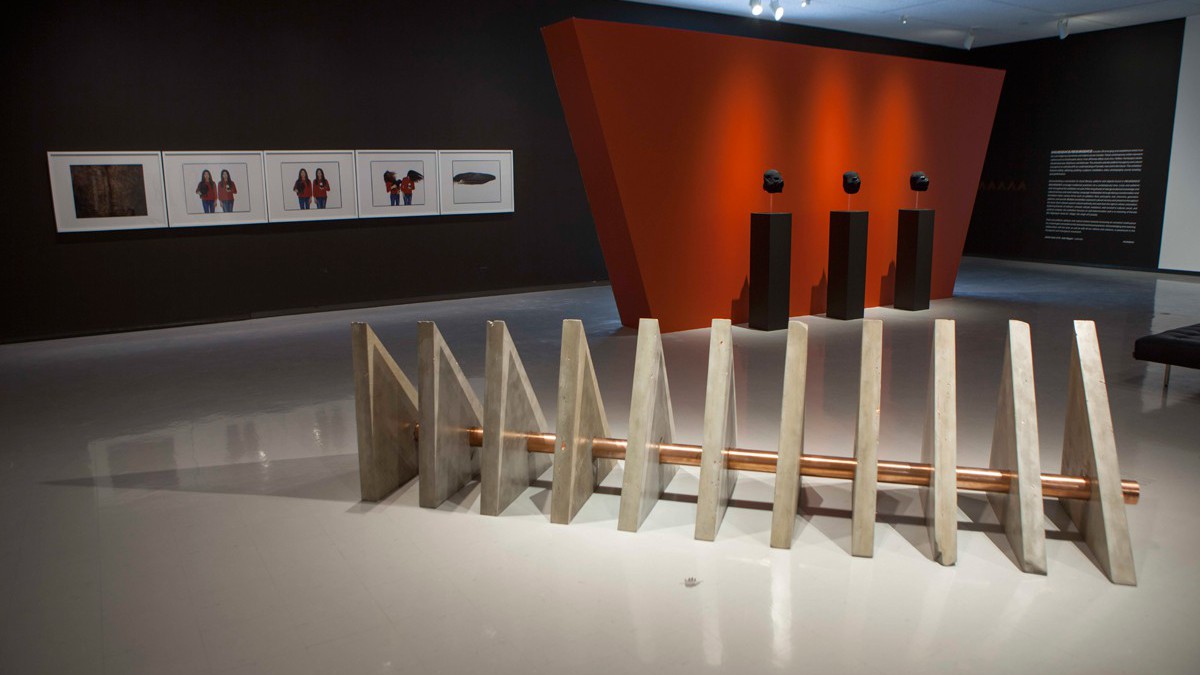

Among these pieces are two stunning conceptual sculptures, one by Caroline Monnet and another by Frank Shebageget. Monnet’s Shield (2017) is composed of sturdy copper pipe holding together a series of triangular concrete forms aglow with copper dust. From either end the triangles appear to fan out, disarmingly graceful despite their mass, and echoing the WAG’s architecture. The piece resembles a spinal cord and vertebrae, a chain of information, and interminable strength and resilience. At the back of Gallery 9 hangs Frank Shebageget’s Cell (2010), a delicate white cube formed by gauzy fishing nets and steel hooks, an answer to Western minimalist art.

The show explores themes relating to Indigenous values, traditions, contemporary culture, and political issues. It doesn’t prescribe an airtight rationale to the presence of the works alongside one another. The curatorial vision presses the audience to reconsider the gallery experience and reimagine the gallery itself through a lens of political action (insurgence) and cultural strength (resurgence). This recasts the WAG in a favourable light, as the gallery has been dogged by a stuffy, institutional vibe and has been angling for a new identity for years.

Arguably the greatest success of INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE is that it has drawn in people who may otherwise feel the WAG isn’t a place for them. Community use of the space has included a Red Rising Magazine issue launch and the Initiative for Indigenous Futures symposium, the latter a gathering of artists, scholars, and community members focused on imagining what the future could look like for Indigenous communities.

While it’s not unusual for exhibits to be sponsored by corporate donors, INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE’s presenting sponsor is the Bank of Montreal, which is an investor in the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline – a proposed pipeline between Edmonton and Vancouver that will severely affect Indigenous communities. This tension typifies the confluence between institutional art practices and commodity culture, illustrating their close alignment and the complexity of our late capitalist society.

Despite the fact that art institutions seem inextricably rooted in colonial practices, this exhibition is undeniably a move forward; it dismantles the gatekeeping tactics used for decades to exclude Indigenous artists from the contemporary mainstream art world. INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE is a bright spot and provides a hopeful sign that we are finding ways to move into something better.

The exhibit is on in Winnipeg until April 22, 2018.