In August of 2009, Chinese police targeted artist and activist Ai Weiwei for agreeing to participate as a witness in the trial of fellow Chinese activist Tan Zuoren. Zuoren had co-authored a report criticizing the local Chinese government for failing to ensure that their schoolhouses were properly constructed before the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that left more than 80,000 people dead or missing.

Weiwei was in the city of Chengdu awaiting Zuoren’s trial when members of the police kicked down his door and beat him. A month later, Weiwei was visiting Munich, Germany, for the opening of his solo exhibition So Sorry when he entered the University of Munich hospital complaining of headaches. After close examination, Weiwei underwent emergency surgery to repair a brain hemorrhage, allegedly the result of the police beating. Wakening to a plastic tube draining blood from a hole in his skull, Weiwei took to Twitter to post photos that became selfies of resistance.

Zuoren’s lawyer had selected Weiwei as a witness because Weiwei was conducting his own investigation into the dead or missing schoolchildren, the Sichuan Earthquake Names Project. Weiwei had volunteers collect data and create a list of victims’ names after the Chinese government failed to publish the names of the dead or missing when 7,000 classrooms and dormitory rooms collapsed during the earthquake. On the one-year anniversary of the disaster, Weiwei posted the names of 5,205 student victims to his blog. “I believe this is the responsibility of the living toward the dead,” he wrote of the project. “If it is not complete, the souls of the living could never be complete.” Chinese officials quickly shut down the blog.

A recent survey exhibition of Weiwei’s work at the Art Gallery of Ontario featured Weiwei’s list of names transformed into an artwork called Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation (2008-2011). In the work, Weiwei printed the names, ages, genders, birthdates, and schools of known student victims across a massive wall. There, traces of the dead or missing were displayed in a solemn public memorial. In documenting the names of the dead or missing schoolchildren, Weiwei’s work resists the Chinese government’s attempt to seal the dead or missing inside a tomb of numbers, as mere statistics.

“A vehicle for ceremony”

China is not alone in its failure to acknowledge a systemic lack of safety for the people it governs. According to a new database created by Maryanne Pearce, a federal civil servant, as part of her PhD research, the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada has risen to 824. But the gauge of such loss does not lie in numbers but in testimony and remembrance, in the stories of affected families and loved ones where quantitative data has little value in qualifying emotional pain.

The federal government has thus far been resistant to addressing the issue. Prime Minister Harper has repeatedly rejected calls for a public inquiry, suggesting it would be a waste of resources. Amnesty International stresses that even the United Nations has repeatedly attempted to instigate a Canadian inquiry. In 2010 the mostly Conservative parliamentary Standing Committee on the Status of Women was formed, but it waited four months to hear any testimony and was widely criticized for its ineffectiveness. On March 7, 2014, the more recent Special Committee on Violence against Indigenous Women released a report which once again failed to call for a national inquiry. In effect, Canada has failed its dead and missing Indigenous women, and now it’s failing a public inquiry as well.

Like Weiwei, artists and artist organizations in Canada have turned to art for accountability and memorialization. Doing so brings artists and communities together so they may gain strength, find resolve, and hold some stillness amid the chaos. One of the most powerful of these works is Vigil by the Anishinaabek artist Rebecca Belmore, performed in Vancouver’s notorious Downtown Eastside. The performance stands as a raw articulation of loss. In the work, Belmore scrubs the street clean, lights commemorative candles, shouts the names of missing Indigenous women scrolled across her arms in black marker, and then tears off her dress.

According to the art historian Claudette Lauzon, “Belmore’s is a body that refuses to vanish from a space in which women’s bodies are expected to vanish without a trace.” The overrepresentation of Indigenous women and girls working in the sex trade goes hand-in-hand with the threat and reality of violence. Belmore’s body and voice present a challenge to the silence engulfing the murdered and missing and the complicity of police services. Ultimately her performance seeks to prevent Vancouver’s missing women from becoming mere statistics.

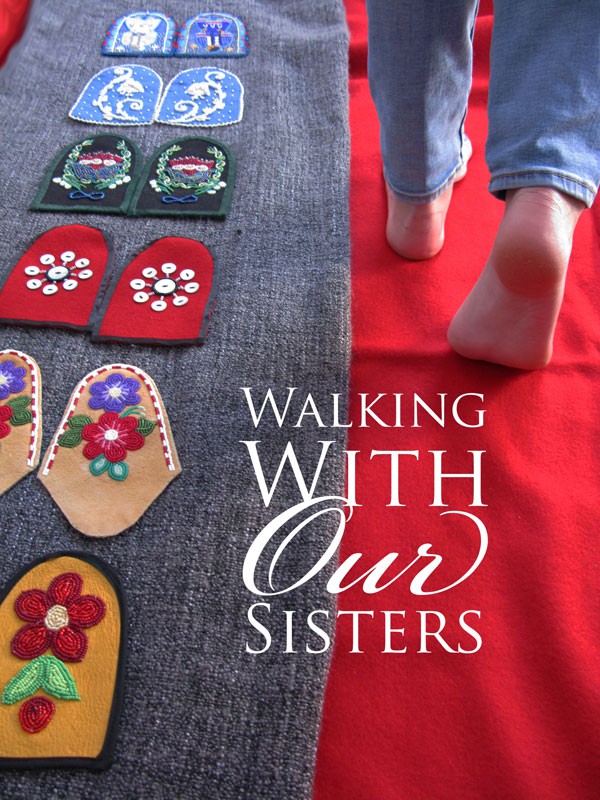

The Walking With Our Sisters project also memorializes murdered and missing Indigenous women, using art and craft to forge social collaborations. It is both an international touring art exhibition and a model for community engagement. To date, 1,372 people – from Brisbane to Munich to Calgary – have contributed self-made moccasin vamps, or tops, which are then displayed on walls and floors of venues.

While each pair of vamps represents a missing or murdered Indigenous woman, the unfinished moccasins represent their incomplete lives. The murdered or missing cannot be present, but the vamps are a marker of their spiritual presence and living memory. “Walking With Our Sisters is actually a vehicle for ceremony, and it is a memorial where the audience and artists participate in the act of honouring,” says Christi Belcourt, an artist and organizer with the project. “It is about respecting the lives of the women and girls through community participation in the piece, and by our consolidated participation, we are declaring that their lives have value.” Walking With Our Sisters is, above all, an act of love and respect, but it’s also an act of justice and intervention.

Whether in university galleries or the Métis Hall in The Pas, MB, each exhibit includes the opportunity for prayer and the symbolic offering of tobacco. As with Weiwei’s project, Walking With Our Sisters has used volunteer collaborators and social media to gather resources. The project has also relied on crowd-sourced funding and online auctions rather than government grants. The auctions raised $38,000 in 20 days in August 2013 which was shared between the grassroots organizations Families of Sisters in Spirit and Tears4Justice.

Though the contexts in China and Canada differ – one an unpredictable natural disaster and the other a systemic breach of human welfare originating in colonization – the government response in both cases screams of transgression. “If we remove the labels of communist or democratic and simply look at the actions of those in power,” Belcourt reminds us, “then politics are a shallow excuse to ignore what we know instinctively to be just.” In these examples, it is clear that art can represent a public inquiry of a different order. It communicates when others do not. Ai Weiwei’s work is radically political because it exposes power’s evasion of accountability. The work’s formal structure – a list of names – means that it can be restaged at sites throughout the world; it is versatile and resistant to censorship.

The subject matter of Weiwei’s work finds a chilling parallel in Stephen Harper’s resistance to launching a national public inquiry into Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous women. Rebecca Belmore’s Vigil and the ongoing Walking With Our Sisters project embrace the lives behind the numbers, using art as a means for knowledge, healing, and accountability.

Visit the Walking With Our Sisters website for ongoing exhibition tour dates.