I am sleeping in a warm cabin two to three hours away from home. It is a crisp spring day with ice and soft snow everywhere.

It is six in the morning and my auntie Lena is fiddling with .22 bullets. “Max,” she calls to me. I squint in the blinding light that glows on the windowpane.

“What are you doing?” I ask, my voice raspy from sleep.

“I need to load this rifle,” she replies. I take the rifle from her and see that she put in the wrong bullets. I shake them out. I load the 25 aught 6 rifle with five bullets and try giving it back to her. “No, you take it,” she says. “Dad is waiting outside.”

I am half asleep, in my blue plaid pyjamas. I put on rubber boots and a jacket, then walk out the door. As soon as I walk outside, my grandfather yells at me: “Shoot!”

I can see the wolverine moving fast in the distance. I shoot. And miss.

“Atii, atii [let’s go, let’s go],” he yells in Inuktitut. I run and jump onto the snowmobile.

As soon as I walk outside, my grandfather yells at me: “Shoot!”

We start to chase the wolverine, which is speeding up. We get closer and I jump off the machine and shoot twice. I miss both times. “Ah! Why do I keep missing?” I ask myself.

I run back to the snowmobile and we take off once again, following the wolverine. It takes a number of sharp turns; we take forever to turn because our old Polaris 550 hunting Ski-Doo, with its worn-out skis, doesn’t turn as quickly as it used to. My grandfather yells “hold on!” I grab the handles of the snowmobile and scream as we run over the wolverine to slow it down.

The strong little bugger keeps going – wolverines have the same strength as polar bears, they say. I get off the snowmobile and shoot at it, hitting its back right paw. It finally slows down, but keeps running, so once again I get on the old Polaris. While driving, my grandfather – the greatest hunter I’ve ever known – asks me how many bullets I have left. “Atausiq,” I reply. One.

He looks back at me and tells me if I miss it, the wolverine will be long gone. My heart starts racing. I get off the snowmobile one last time, and think to myself, “This is it, Maxine, focus! I can’t let him down.”

I take a deep breath, aim, shoot, exhale.

I close my eyes right after pulling the trigger, because I’m so nervous. When I look up, the wolverine in the distance is no longer moving. We drive toward the quickest thing I’ve ever chased. We drive onto half of the wolverine’s body, because they tend to play dead. It doesn’t move.

I close my eyes right after pulling the trigger, because I’m so nervous.

My grandpa turns and looks at me with the biggest smile. “Nakattai!” He means I killed it clean and instantly. My whole body tingles in excitement. “I just shot my first wolverine!” They are not the easiest to hunt.

It is six in the morning, and we are at my grandfather’s favourite place, on our beautiful land of ice and snow. Sivui.

***

I grew up with my grandparents, half traditionally, half not. We lived in Whale Cove, Nunavut, a community of 350 people. My grandfather was the only male role model I had. He taught me how to hunt, fish, build igloos, repair snowmobiles and ATVs, build sleds, and – most importantly – he taught me how to survive if I ever got stuck out on the land. Jack Anguk Senior, “the great hunter of the North,” I called him.

I shot my first caribou when I was five. I remember my grandfather scoping out a herd of caribou on the tundra. He called me over and I knew why. He handed me the rifle and had to help me hold it up.

There were so many caribou that day. My face wasn’t allowed to touch the scope attached to the rifle, so I had to hold my head high. He helped me aim at the thousands of caribou in front of us, and told me to pull the trigger. I closed my eyes and used three fingers to pull. BANG! It went off and I had the biggest smile on my face. Seconds later he grabbed the rifle and shot another. We drove toward the caribou and there were the two we shot, on the ground.

My grandfather always cut up the meat before heading home, putting different body parts in separate bags for Elders who liked certain parts of the animal.

I learned to drive an ATV when I was around seven or eight years old. I was old enough to bring the bags of meat to the Elders in my community. These were Elders who were either too old or widowed, or who didn’t have the transportation to hunt. They would all smile and say thank you. There was one Elder in particular who would always say to me “tuktuchiajuvaalu!” meaning, “You shoot the best caribou!”

I had my grandfather to thank for that – he was known to shoot caribou with the most fat.

Jack Anguk Senior, “the great hunter of the North,” I called him.

We were poor, and we ate a lot of traditional food. My family and my community ate all the animals that were around us. We ate them raw, dried, cooked, boiled, fermented, and frozen. Caribou, fish (Arctic char and lake trout), beluga whale, goose, seal, ptarmigan, polar bear, and other animals from farther away, like bowhead whale, muskox, walrus, and narwhal.

I remember how some of them tasted. Beluga has a strong, fishy, seawater smell to it – we ate it cut up in small pieces and dipped in soy sauce. Seal has a rich taste and darker meat, and when it’s boiled the smell is strong. But my all-time favourite will always be caribou. The taste is somewhere between moose and deer, but caribou doesn’t taste gamey or strong – it’s perfect. It is said that if you eat a whole caribou – its brain, eyeballs, bone marrow, right down to the insides of its hoofs – it will give your body all the vitamins you need.

All these animals keep Inuit warm and strong. There are no trees where we come from, and we had little access to vegetables. When they were flown into the only store in town, they were overpriced and half rotten. So we ate animals and berries from the land, and other foods like eggs and bacon, frozen pizza, and Kraft Dinner.

When I was 12, I was selected to travel to Vancouver to attend a Canadian student leadership conference for 10 days with another classmate and my teacher. This was the first time I had left my hometown without my parents. When we arrived in Vancouver there were teenagers from all across Canada; I was the youngest one attending.

It is said that if you eat a whole caribou – its brain, eyeballs, bone marrow, right down to the insides of its hoofs – it will give your body all the vitamins you need.

One night I was hanging out with a bunch of kids, kicking around a hacky-sack. One of them asked me “what I was.” I proudly said that I was Eskimo – at the time, the term Inuit was just being introduced to people outside of Inuit Nunangat. The kids started laughing and called me a “raw meat eater.”

I walked away and kept my distance from those kids as the days passed, but their words never left my mind.

When I arrived home, I walked into my grandparents’ house, and there was cardboard on the floor heaped with frozen caribou, fish, and beluga whale. My grandfather had welcomed me home with all this food. I told him I didn’t want any of it. I couldn’t eat it; I’m an Eskimo.

He didn’t ask me why. But he never stopped asking me if I wanted to eat the food he hunted, even though I always said no.

A couple years later I tried eating beluga whale again. I threw it all up. Today, I’ll only eat caribou and fish – but even then, it must be cooked.

***

I knew when I was 12 that I liked girls. When I was younger, I’d started wearing boys’ clothes. We had to go to Sunday school, and one of teachers once talked about two people of the same gender being together. It was a sin, they said, and if you are attracted to the same gender you will go to hell. I was so scared of going to hell. I tried to like boys but no matter how much I tried, it never worked. This was something I had to hide until I moved away when I was 23.

I tried to like boys but no matter how much I tried, it never worked. This was something I had to hide until I moved away when I was 23.

In my culture there were gender roles, something that has existed for thousands of years. Inuit women stay inside to watch the kids, sew, and clean. Inuit men make tools, keep the dogs fed, and hunt, walking for miles on the tundra where the weather can change drastically. This was the way it was in my family – my grandpa hunted and my grandma sewed.

When I was in high school, there was shop class for boys and cooking and sewing for girls. I refused to go to sewing class, so I would leave and join the boys instead. I would get in trouble, so I stopped going to class altogether. I told my teacher that I wouldn’t come to school if I couldn’t attend shop. Finally, the school relented. I learned how to make Inuit traditional tools in shop class instead. We built hunting sleds and went out on the land, and we learned how to build igloos. I loved everything about it.

***

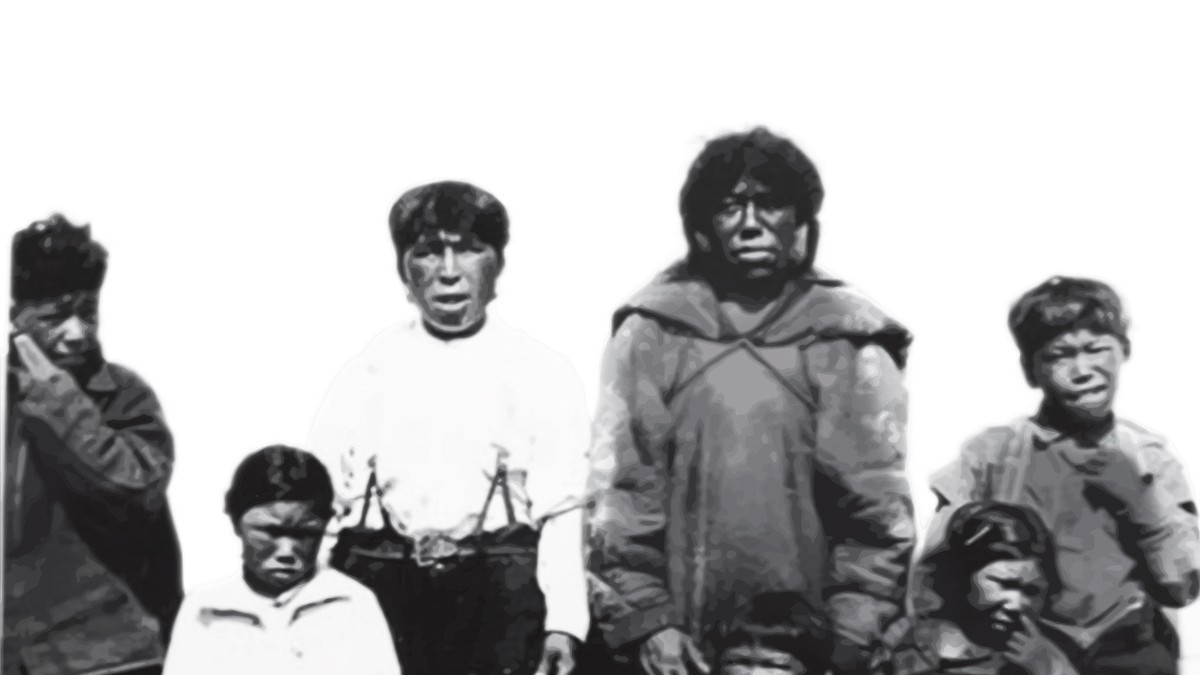

In my family we are all tall and dark – some of us are slender and some are heavy-set. When I meet people today and tell them that I am an Inuk, they tell me that I don’t look like one. A lot of Inuit back in the day were short and stocky and their facial features were distinct. I often tell them that I come from an interesting bloodline.

In the 1900s, whalers travelled across Hudson Bay to hunt whales. Many of those shipmen were slaves from the west coast of Africa. I never understood why my grandfather’s skin was darker than the rest of the Elders in my community. I thought it was because he was tanned, from always hunting.

I never understood why my grandfather’s skin was darker than the rest of the Elders in my community.

After he passed away in 2006 I started looking for more information about his side of the family. I discovered that my grandfather was part Black – his mom was half, and her biological dad was a Portuguese man who came from Cape Verde, Africa. His name was Brass Lopes. He was the boat steerer as well as a harpooner on the famous American whaling captain George Comer’s ship.

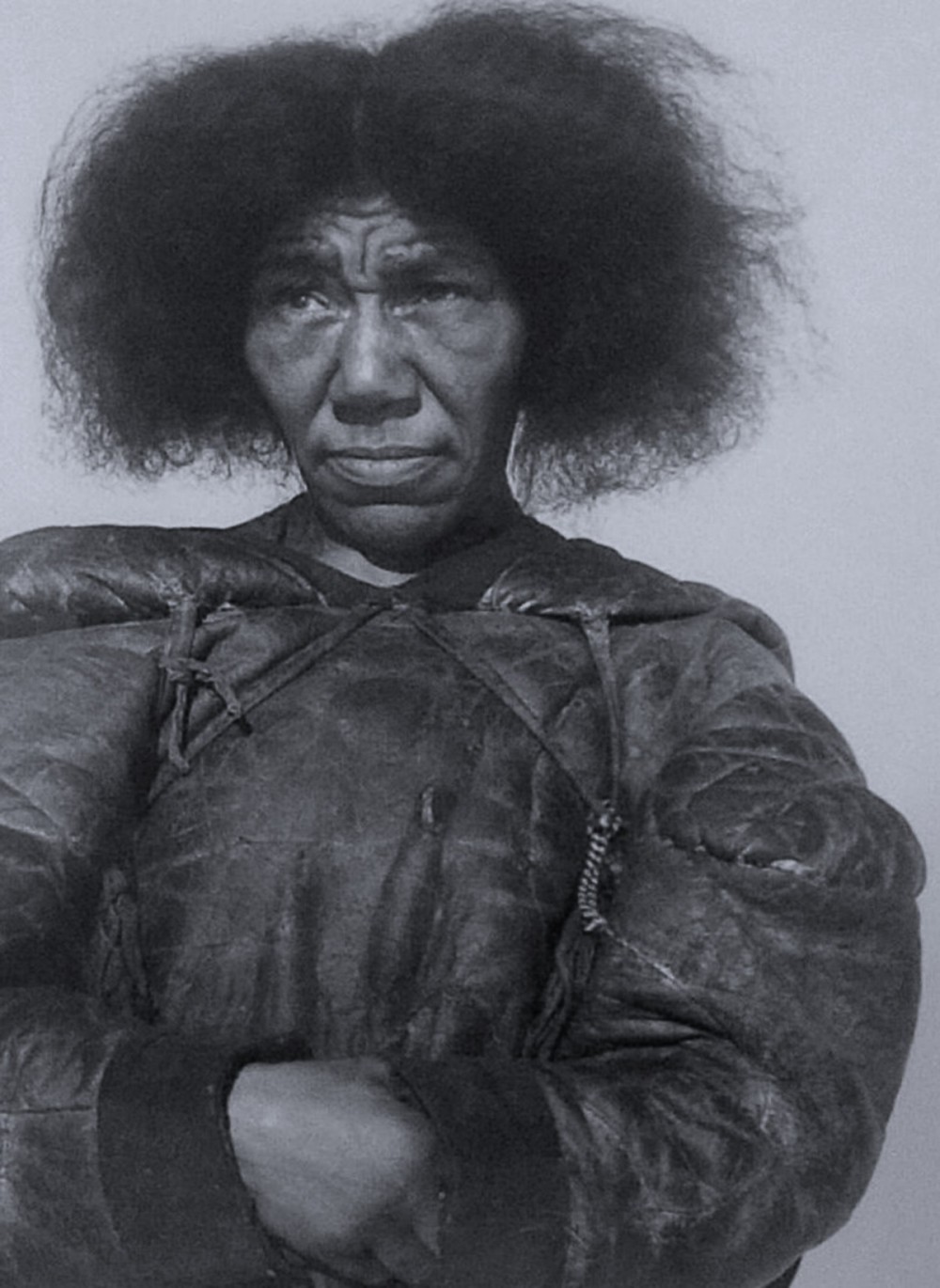

My great-great-grandfather’s name was Jack Anguk (my grandfather was named after him). He was married to my great-great-grandmother, Monica Anguliq. They couldn’t have any children so they both agreed that she should conceive with a whaler – Brass Lopes. When a baby girl was born, she was named Ikuaalaaq, which means “fire,” because of her frizzy hair.

Ikuaalaaq was an only child, but had eight children of her own – I was told that there could’ve been more. She survived the famines in the ’50s and ’60s. Her husband died by suicide, so she had to hunt and fish while the kids stayed in the igloo, until her sons were old enough to hunt. My grandpa’s younger sister, Autut, would tell me stories about her – she told me about a time when Ikuaalaaq had to carry two seals by herself, dragging them for miles across the land to feed her kids.

***

My last trip with my grandfather was to Sivui in 2005, when I shot my wolverine. My grandmother told me Sivui had been a huge man who had always caught big fish there, so the land was named after him.

In the summer of 2017 I adopted a little girl, newly born to my niece. We thought she was going to be a boy and I planned to name her Jack, after my grandfather. After she was born we named her Quinn (because it’s gender-neutral) Jackiah (after my grandfather) Sivui Angoo.

I also have a nine-year-old step-daughter, Melody. I named her Aputi, which means “snow” in Inuktitut.

She told me about a time when Ikuaalaaq had to carry two seals by herself, dragging them for miles across the land to feed her kids.

I hope to raise my daughters as I was raised, although it’s more difficult because we live in Manitoba. I speak to them in my language, I make sure that they spend time with my friends and family who visit me in the city, and I make sure they eat traditional food when it is sent to me.

I took Melody and Sivui to Whale Cove in the fall of 2017 and they absolutely loved it – Melody is always asking me questions about hunting and Inuit games, and asks when we’re going back. She sings along to the Inuktitut songs we play on YouTube.

My biggest wish for my girls would be for us to move back home for a year or two, so they can hunt and fish out on the beautiful land I’ve walked on. I want them to shoot their first caribou. I want Sivui to travel to the place she is named after, to see where I was most happy. I want her to be an amazing fisherwoman.

Until then, I will do my best to raise her and Melody knowing my culture, stories, songs, games, language, and – most importantly – my family.

***

Jack Anguk, 1938–2006. These are some of my most precious years, because of my grandpa’s presence. The day I shot my wolverine is a day that I will remember for the rest of my life, because I know it was a day I made my grandpa proud.

This is for you, Ataatatsiaq. Forever with me in memory and spirit.

This article was the winner of Briarpatch’s first Northern Writing Prize.