Water control is out of control in Canada. The latest case in point: a sprawling network of thousands of dams, diversions, dikes, ditches, drains, and culverts that has emerged in the Saskatchewan River delta – the largest freshwater delta in North America, located in and around Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN) in Manitoba and Cumberland House Cree Nation in Saskatchewan – that many locals have grown increasingly wary of. The actual purpose of the dams and other water-control structures is not clear, and they have ruined lakes, rivers, and creeks.

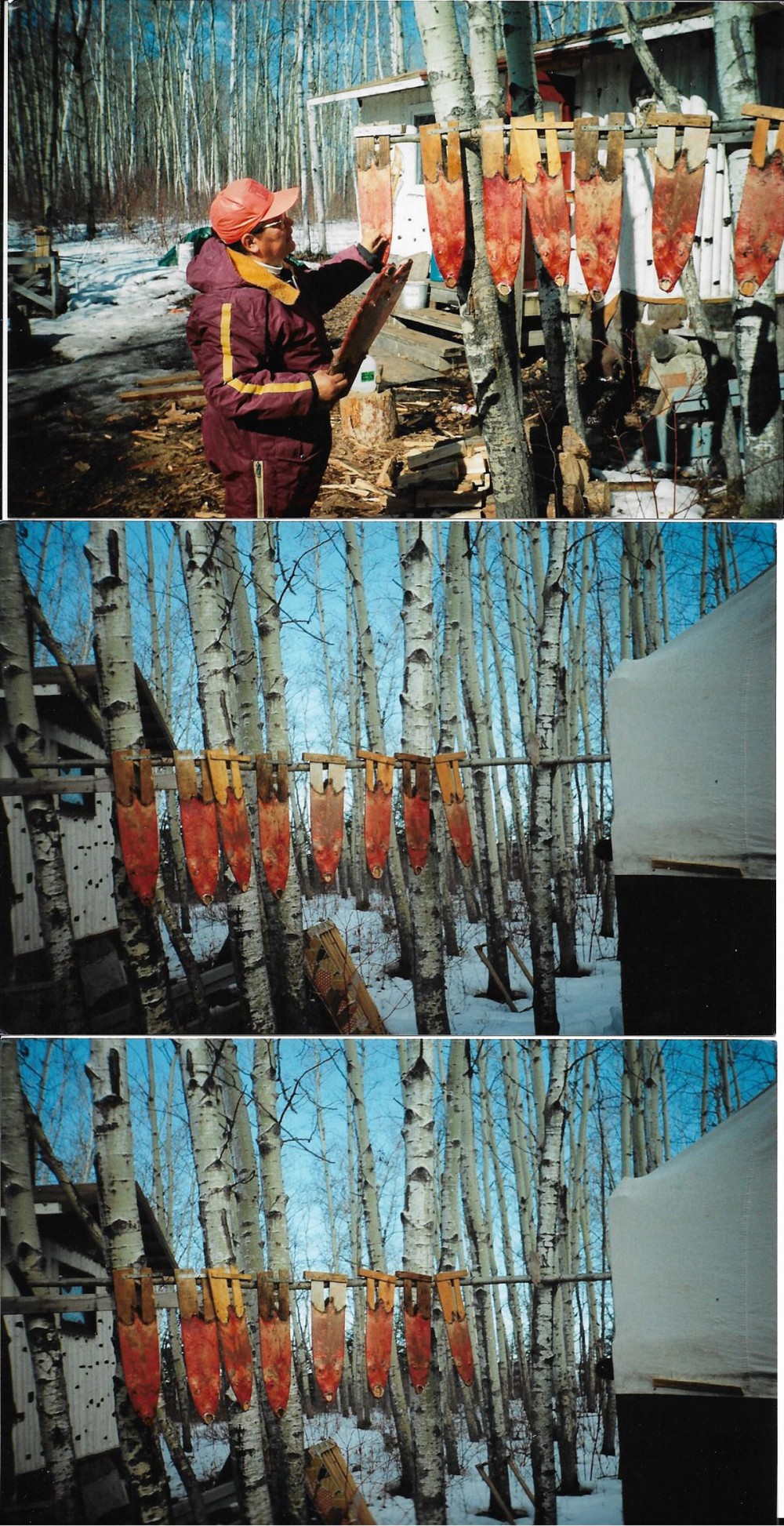

Cecilia Ross, 80, is an OCN Elder, teacher, trapper, and retired health authority director with a camp on the Saskatchewan River. Routes that Ross travelled all her life have been rendered unnavigable. “They put three huge dams on that river and we don’t know why they did that,” Ross tells us. “It’s not doing anything; all it’s doing is it damaged the river system.”

“They used to maintain them at first … they did that for four years and then they left it. Now it’s ruined, it’s dry.”

“They put dams on those lakes, toward the river. They put dams on the creeks going into the river. They dammed everything. And now they’re not looking after anything. I don’t know what their reasoning was,” she adds.

The structures operate erratically, Ross says. On one lake that she frequents, Ross tells us, “All the water was gone for a whole summer. Then they put the water back in the fall, but that did a lot of damage to that lake.” Some of the structures are maintained for a while and then abandoned. “They put all kinds of dams all over … they put culverts,” says Ross. “They used to maintain them at first … they did that for four years and then they left it. Now it’s ruined, it’s dry.”

The mysterious structures have dispossessed people, fish, and animals of traditional sites that had sustained them for hundreds of generations. Pat Personius, 84, is an OCN Elder, trapper, and retired equipment operator at the paper mill near OCN. “Most of the lakes are stagnant and they smell” as a result of the dams and other structures, Personius tells us. “The creeks going to the lakes are pretty well all dammed, and that’s where the fish used to go to spawn. Now they can’t even get to their spawning grounds, and there’s hardly any fish in the rivers now … the fisher[s] and the trappers can’t even make a living.” One winter, says Ross, “they opened that dam, most of the water went out, and they froze those muskrat houses, and all the muskrats died that winter.” The same dam flooded and destroyed habitat for mink, otters, wolves, and moose, Ross says. “And our trapping areas, we can’t trap on a creek if it’s flooded.”

Ross and others have taken to interfering with the structures in order to maintain their livelihoods and to do what they know is right. “My husband and I used to open them,” says Ross. “We used to maintain our own lake. We used to open the dam. Sometimes the beavers would help us.” Beavers are among the most committed opponents of the structures. “It was a funny story,” Ross goes on. “They had built a man-made channel from the river to the lake, and on that channel there were beavers, and when they pulled out all those four-by-fours, the beavers laid a dam on that man-made channel, and they plugged it up. ‘Good for them,’ I said. They can’t control the beavers.”

"I called the rest of them, come out here, what’s wrong here? Do you realize what’s going on? Do you realize there’s no birds?"

The network of water control structures in question is owned and operated by Ducks Unlimited Canada, a private charitable organization with annual revenues of $95 million and assets totalling $447 million in 2019. As a result of decades of committed work by Indigenous activists, the destruction of Indigenous territories by hydroelectric dams in Canada and around the world has become widely known. So too has the destruction of Indigenous communities such as Lake St. Martin, Manitoba, by provincial flood-control structures and the disfigurement of Shoal Lake #40 First Nation, by the city of Winnipeg’s drinking-water infrastructure. Ducks Unlimited – which controls more land and water in Canada than all First Nations combined – deserves its own chapter in the story of colonial water control in Canada.

Ducks Unlimited, once referred to as the Duck Factory, is not shy about its one goal as an organization: generate more ducks. But their actions near OCN seem to be having the opposite effect. “[Ducks Unlimited] said they wanted to help the ducks to populate, give them a place to nest,” says Ross, “They put islands on there. Those ducks didn’t nest on those islands … I went there, I didn’t see any ducks there.” In fact, ducks have almost vanished from some areas of the delta targeted by Ducks Unlimited. “The other thing I noticed, the past two years we’ve been going down to my camp,” Ross shares, “You won’t believe this. There’s no birds. One evening I was sitting outside … I called the rest of them, come out here, what’s wrong here? Do you realize what’s going on? Do you realize there’s no birds? This was in the fall, usually you would hear the birds.” Ross goes on, laughing, “Lana said, ‘maybe there’s a sasquatch here.’ ‘I don’t think so,’ I said.”

“There are hardly [any] ducks anymore,” Personius agrees. “There used to be plenty of ducks around.” The gap between what Ducks Unlimited says they do and what they actually do is a mystery that Ross, Personius, and others in the OCN and the Saskatchewan River delta want to solve. If this formidable organization – with the resources, capacity, and motivation to significantly rearrange the way the water flows – is not doing what it says it is doing, then what is it doing? Is it a matter of failure, or of hidden intentions?

In 1929, New York City newspaper mogul Joseph P. Knapp and factory owner Arthur M. Bartley founded More Game Birds in America, an organization designed to promote the conservation of ducks for sport hunting. As it turns out, duck hunting is a pastime dear to the hearts of U.S. industrialists – equivalent, perhaps, to golfing, skiing, or cigar smoking. Major early sponsors of More Game Birds in America included large U.S. arms and ammunition dealers, General Mills, and Chrysler. As they and their peers hurled masses of working people into unemployment during the Great Depression, the members of More Game Birds in America urged their class to take seriously another crisis: a shortage of ducks it dubbed a “Duck Depression.”

The ethos of More Game Birds in America was to apply scientific management techniques to the natural world in order to increase duck production, just as its founders had done in their factories. “Man must help Nature produce” was their unofficial motto. A duck census conducted between 1933 and 1935 discovered that 85 per cent of ducks in North America originated from an area spanning Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa – a zone dense with small ponds, lakes, and marshes, called the prairie pothole region. Of the 42 million ducks counted in the prairie pothole region, 40 million were found in Canada. In 1936, More Game Birds in America published Ducks Unlimited, “A practical plan to perpetuate and steadily improve duck shooting in the United States by the production of millions of more wild ducks annually through the restoration and businesslike management of Canadian duck breeding grounds.” In 1937, it sponsored the incorporation of Ducks Unlimited in Washington, D.C., and two months later underwrote the incorporation of Ducks Unlimited Canada, in Winnipeg. Ducks Unlimited, Inc. would raise money in the United States for Ducks Unlimited Canada to spend. Over the next 70 years, U.S. donors to Ducks Unlimited would funnel nearly $1 billion into water-control activities in Canada.

Ducks Unlimited – which controls more land and water in Canada than all First Nations combined – deserves its own chapter in the story of colonial water control in Canada.

In its first four decades, Ducks Unlimited Canada worked exclusively in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. “Duck Factory No. 1” at Big Grass Marsh, near Plumas, Manitoba, was the first project undertaken by Ducks Unlimited Canada – and it was, coincidentally, near the Lake Manitoba duck-hunting lodge of James Ford Bell, founder of General Mills. The organization’s typical approach was to prevent bodies of water from drying up by building a dam to stop water from flowing out through existing channels and by building dikes along its edges to prevent water from flooding out onto surrounding fields. The first directors of Ducks Unlimited Canada were the Canadian doppelgangers of its U.S. founders: Winnipeg wheat king James A. Richardson; Saskatchewan judge W.G. Ross; Calgary newspaper executive O. Leigh Spencer; and the son of a militant anti-labour lawyer, Edward Pitblado.

From the beginning, Ducks Unlimited Canada’s well-connected directors secured federal and provincial government permission – and often funding – for its activities. Ducks Unlimited Canada predated most Canadian state efforts to conserve wetlands, and Canadian governments seemed ready to accept philanthropists’ offers to finance a supposed public good that they had no intention of orchestrating themselves. When governments later crafted their own wetland conservation strategies, starting in the 1960s, they largely imitated Ducks Unlimited Canada’s approach.

Ducks Unlimited immediately targeted the Saskatchewan River delta, building several water-control structures there with the permission of the province of Manitoba, starting in 1939. In 1958, under the authority of the Indian Act, the federal Department of Indian Affairs gave Ducks Unlimited permission to build a dam on OCN reserve land. According to Indian Affairs, OCN also gave Ducks Unlimited permission to build the dam. Ducks Unlimited built its biggest structures in the area in the 1960s and 1970s, sometimes claiming that their intention was to fix damage done by the enormous new Manitoba Hydro dams of those decades.

Ducks Unlimited Canada predated most Canadian state efforts to conserve wetlands, and Canadian governments seemed ready to accept philanthropists’ offers to finance a supposed public good that they had no intention of orchestrating themselves.

During this time, the Saskatchewan River delta became the largest Ducks Unlimited water-control project in North America. Four of Ducks Unlimited’s six major areas of intervention within the Saskatchewan River delta directly surround OCN: the Carrot River Triangle and the Reader-Root Complex to the west, and the Summerberry Marsh Complex and the Tom Lamb Wildlife Management Area to the east. (The two other major areas are the Cumberland and Siisiip marshes, near Cumberland House Cree Nation in Saskatchewan.) Ducks Unlimited controls at least 13 major dams in the vicinity of OCN, most located on so-called Crown land and many partially funded by the province of Manitoba.

While Ducks Unlimited has a long-standing working relationship and memorandum of understanding with the province of Manitoba, its relationship with OCN is not as clear. “OCN may have an agreement for on reserve but does not have a [written] agreement with DU for our traditional territories,” Diane Ballantyne of OCN Natural Resources wrote in an email. She says that for their traditional territories, as far as she knows, OCN only had a verbal agreement, which was that Ducks Unlimited was to take care of the land. It is safe to say that Ducks Unlimited did not honour that agreement. “They don’t consult with the trappers or the fisher[s],” says Ross. “They should have asked them.”

Ducks Unlimited’s function as a toy for its heavily polluting industrialist founders has persisted through its history. For years, the organization sold the naming rights to lakes in traditional Indigenous territories to its wealthy donors. In 1988, as a gift to Arthur Irving, billionaire owner of Irving Oil, upon Irving’s retirement as president of Ducks Unlimited Canada, it carved a Ducks Unlimited logo the size of two football fields into a New Brunswick marsh.

As they have come under increasing fire for destroying the Earth, major polluters have incorporated Ducks Unlimited into their broader greenwashing campaigns, aided and joined by the Canadian government. The country’s biggest banks, oil companies, and industrial agriculture firms – including Enbridge, Pembina Pipeline Corporation, TC Energy, Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline, AltaLink, Cargill, Nutrien, Bayer Crop Science (formerly Monsanto ), the Royal Bank of Canada, and the Bank of Montreal – are prominently advertised donors to Ducks Unlimited. As recently as November 24, 2020, the federal minister of environment and climate change celebrated the government’s support for Ducks Unlimited’s purchase of 488-acre St. Luke’s Marsh on Lake St. Clair in southwestern Ontario by proclaiming, “Wetlands play an important role in the fight against climate change.” Of course, the global impacts of carbon emissions from the construction of pipelines for oil production dwarf whatever wetland conservation Ducks Unlimited has achieved.

The actual purpose of Ducks Unlimited’s water-control structures in the Saskatchewan River delta remains a source of suspicion for OCN residents. “I think they do it for the farmers,” says Personius, noting that Ducks Unlimited has drained wetlands that were later converted into farmland. On its website, Ducks Unlimited insists that it does the opposite, “restoring” drained wetlands before selling the land to farmers at a reduced price. On the other hand, Ducks Unlimited has long antagonized farmers, including those near OCN, by flooding farmland, fencing off grazing areas for cattle, and cancelling long-term haying and grazing leases. Other community members have speculated that Ducks Unlimited plans to eventually divert freshwater to the United States via the Garrison Diversion in North Dakota or to large agricultural operations in southern Manitoba. The province of Manitoba has long opposed the Garrison Diversion, and water flow between Canada and the U.S. is tightly governed by international water treaties – but this suspicion speaks to the level of distrust of Ducks Unlimited by OCN residents. Now that fresh waterways are connected and can be controlled, there is one less barrier preventing freshwater diversion to the U.S.

Regardless of Ducks Unlimited’s motivations, it is clear to Ross and Personius that the time has come for collective action against the Duck Factory. “I would like to see the community do something about it,” says Ross. “We talked about it a year ago.”

“You can go after Manitoba Hydro, but it seems like we can’t go after Ducks Unlimited.”

“Before COVID I asked the Chief and council to go after Ducks Unlimited,” says Personius. He points out that the same tradition of resistance to hydroelectric dams should be turned toward Ducks Unlimited, even if the latter’s status as a private entity makes it more difficult. For example, years of organizing by Cree First Nations forced Manitoba Hydro to provide reparations to the Indigenous communities it has harmed, as stipulated in the 1977 Northern Flood Agreement. The fight for true justice continues, for example, through the work of Manitoba-based Wa Ni Ska Tan: An Alliance of Hydro-Impacted Communities. But “nobody touches Ducks Unlimited,” explains Personius. “You can go after Manitoba Hydro, but it seems like we can’t go after Ducks Unlimited.” The dams and culverts should be removed, Ross and Personius say, and fishers and trappers should be compensated by Ducks Unlimited for the loss of their livelihoods. Above all, says Ross, “we could ask them to leave things alone.”

“It was a big mistake,” Ross declares. “I think man should just leave nature alone, let it do its own thing. Things were good. Things were better. Leave things be.”