This article was the winner of the 2019 Northern Writing Prize.

The July air is cool. Whitefish and sausages smoke on a grate above the fire. Hot coffee sits in a kettle by my side.

The kids are playing by the water. I sit around the fire with the adults, listening to them talk. About the day, about a game of capture the flag we played earlier that afternoon, about life here in Old Crow.

At 128 km north of the Arctic Circle, situated on the banks of the Porcupine River that connects Canada and the United States, Old Crow is one of around a dozen Gwich’in communities and home to around 250 members of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. It is also the only fly-in community in the Yukon.

It is my second day in the community. I’m one of six journalism students who have travelled to the Yukon because our professor believes that, in order to be a good journalist, one must spend time with the people whose stories you seek to share.

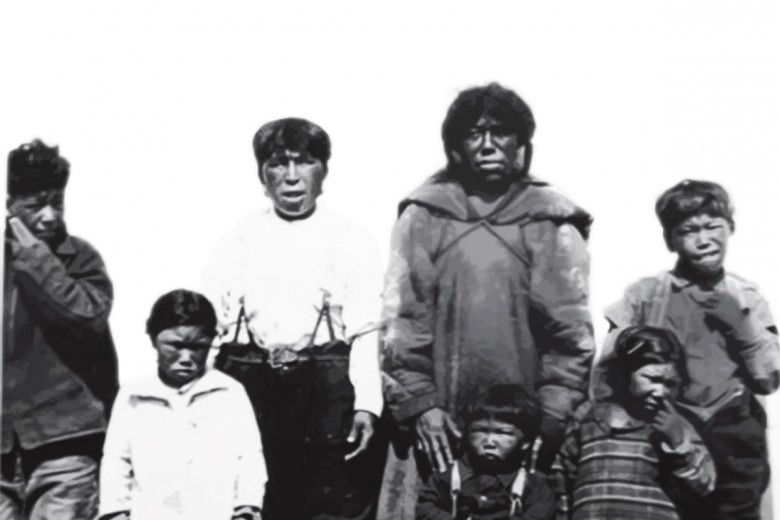

The Gwich’in are part of a larger family of Indigenous peoples known as Athapaskans and one of the most northerly Indigenous communities on the North American continent, second only to the Inuit. The Gwich’in way of life remains – both culturally and economically – anchored to the land through hunting, fishing, and trapping. Today, we are at the T’loo K’at campground for the Vuntut Gwitchin government’s summer family salmon fishing camp. And it is at this camp, after a day of being out on the water, of visiting the nets, of seeing how whitefish is cleaned and smoked, that I begin to understand what it means to be an outsider in Old Crow. A tourist.

It means there is so much I don’t know, and so much I have yet to learn. It means that for every new thing I learn about the Yukon’s northernmost community, there are twice as many things I must unlearn.

A state of emergency

On May 19, under the leadership of Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm, the Vuntut Gwitchin Council gathered in Old Crow to declare a climate emergency. The declaration was titled “Yeendoo diinehdoo ji’heezrit nits’oo ts’o’ nan he’aa” in Gwich’in – which, in English, translates to “After our time, how will the world be?”

“[C]urrent State-led responses to climate change around the world are not sufficiently responsive to the dire circumstances already being directly experienced[,] and the implications for the health of animal populations, food security, as well as our communities[’] emotional, cultural, and physical well-being,” the declaration reads. The council was “[c]oncerned that Indigenous peoples[’] voices and lands are not being heard.”

According to a report, page 116 released by Natural Resources Canada in April, between 1948 and 2016, northern Canada saw a 2.3 C rise in average annual temperature – three times the global average.

“We, here in Old Crow right now, have -27 C,” Joseph Tetlichi tells me when he calls me in November. “That’s normal temperature for this time of the year. However, we’ve got no snow.”

“Normally, by October 1, we should have three to four feet of snow. The river should be frozen, the lake should be frozen. That hasn’t happened.”

“Our people can’t even drive their Ski-Doos yet,” he says. “The lake freezes, and if it freezes people are still cautious of going out on the land because the mild weather and the conditions of the ice are unheard of.”

For 25 years, Tetlichi has been a member of the Porcupine Caribou Management Board (PCMB), which works to preserve the herd of roughly 200,000 Porcupine caribou that migrate between the Yukon, Alaska, and the Northwest Territories. But more recently, “because of the warmer temperatures, the Porcupine caribou are acting differently in regards to migration patterns,” he says.

The Porcupine caribou herd ranges over 250,000 sq. km of northern tundra, migrating between the Yukon’s Arctic coast and Alaska in the spring and the Yukon’s Ogilvie Mountains in winter.

Since the first census in the early 1970s, the size of the herd has fluctuated dramatically. In 1972, the herd size was 100,000 individuals, increasing to 178,000 in 1989, declining to 123,000 in 2001, and shooting back up again to over 202,000 in 2017. And while the Porcupine caribou numbers are currently among the highest ever recorded, less than half of all Canada’s barren-ground caribou remain, with the populations of some herds having declined by over 90 per cent from historic averages. Across the Arctic, tundra fires have destroyed the lichen that barren ground caribou feed on, while spring rains can freeze and block access to lichen and plants. Thinning sea ice has made ice crossings impassable or precarious.

The Porcupine caribou are changing their migration patterns in response to these climatic changes. “We have a situation where they come from the calving grounds and just go to the Alaska-Canadian border, and all of a sudden veer west, moving towards Dalton Highway in Alaska,” Tetlichi says. “In the last three to four years, they’re seeing winter in Alaska. Before, this wasn’t their habitat range.” And although the herd has been known to winter in different locations, hunters have said that their migration patterns – from their route to group size – have been more unpredictable in recent years.

Add to that the fact that, in September, the Trump administration finalized a plan to allow oil drilling in the entire 1.6 million-acre coastal plain of Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which the Gwich’in call “Iizhik gwats’an gwandaii goodlit” (the sacred place where life begins). The refuge is the main calving ground for the Porcupine caribou herd – and it’s also believed to be home to the largest untapped reservoir of onshore oil in the U.S., crucial to American fantasies of energy sovereignty.

The Gwich’in are fiercely opposed to oil and gas development in the Alaska refuge. Chief Tizya-Tramm testified before a U.S. congressional subcommittee that “this development on [Alaska’s] coastal plain amounts to the cultural genocide of the entire Gwich’in nation. […] If you drill in this sacred place, it will destroy the caribou, and therefore destroy the Gwich’in.”

The caribou are deeply important to the Gwich’in – along with moose, whitefish, and salmon from the Porcupine River, the community relies on the caribou for food, and pays close attention to their migration. Until around 1920, the Gwich’in used wooden structures called caribou fences that funnelled caribou to a corral where they could be killed. Seven of the 46 known fences are located in Vuntut National Park, about 50 km north of Old Crow.

Tetlichi says that due to these changes in the caribou’s migration patterns, the herd is no longer passing directly through Old Crow, as it once did. Now, hunters have to go farther afield to hunt the caribou. Hunting season has become more unpredictable, since community members don’t know when the herd will be travelling in and around Old Crow, or how long the migration will last.

“We used to [be able to] predict when the caribou was going to come and when they would go,” he says. “All that is what used to be, and now we just have to hope. We just have to hope that the Porcupine caribou will come.”

“They just want to be immersed in our culture”

South of Old Crow lie three small caves, named the Bluefish Caves. In 2016, carbon dating on animal bones found in the caves revealed them to be 24,000 years old, displaying signs of being worked by human tools. The bones offer insight into the beginnings of human habitation in the area as well as the revelation that Indigenous people may have lived here 10,000 years earlier than scientists previously thought.

But after millennia of living in isolation, flights into the community have become a daily occurrence thanks to Air North, an airline in which the Vuntut Gwitchin government invests. As Old Crow nurtures a fledgling tourism industry, the people of Old Crow are now asking questions about what it means to invite tourists in – but also, more importantly, what visitors will take with them when they leave.

Paul Josie is a former councillor with the Vuntut Gwitchin government and owner of Josie’s Old Crow Adventures, a family-run tourism company. Josie takes visitors dogsledding, out to watch the northern lights, and on tours of the nearby Crow Mountain. During these trips, he shares stories of Old Crow as his ancestors saw it and what he sees now.

“A lot of our stories are already in books, a lot of our knowledge is out there,” he explains. “But just for someone to come up and hear it from someone first-hand makes it more authentic.”

Josie believes being out on the land is the best way for outsiders to understand the impact of climate change on the community.

“I think it really puts things into perspective. You can hear about it, you can read about it, but [it’s important to see] it first-hand and [talk] about it, saying ‘here are the changes that have happened.’”

“We’re faced with a lot of other things right now, like the Porcupine caribou – with the drilling in the calving ground – and climate change,” Josie adds. “I talk about these changes that are happening.”

At his camp, Josie gets travellers to help him clean and smoke the fish he catches. He says it encourages conversation about the declining salmon population.

According to a report released by the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee in 2016, between the early 1980s and the late 1990s, the number of Chinook salmon travelling up the Porcupine from Alaska averaged 120,000 fish. But because of rising water temperatures caused by climate change, since 2010 the salmon numbers have dropped by half, averaging 60,000 fish each year.

“Over the years, we’ve seen people paddle up the Porcupine River and they’re doing it on their own, and we always see them come to our camp,” he says. “They want to help us with salmon fishing, they want to hang the nets. They just want to be immersed in our culture. Other people come up and look for us, and they just want to have that authentic experience about what we do on the land.”

Jackie Frederick is the owner of the Hotkey Group, a company that helps small communities in the north of Canada develop their tourism industries. Originally from British Columbia, Frederick first visited Old Crow with Yukon First Nations Culture and Tourism Association (YFNCT) in 2016. She says the community of around 250 people does not yet have the necessary infrastructure to host more tourists. The community has only five homestays, no restaurants operating year-round, and a lone Co-op to provide groceries to the entire community.

She says that tourism presents an opportunity for the community to grow its economy. “If we were to bring a group of six, eight, 10 [people], what are the options for food? We have to start thinking – if you’re in the tourism industry – how you will feed people?”

Bathsheba Demuth, a professor at the Institute for Environment and Society at Brown University, is one person who knows what it’s like to be a visitor in Old Crow. She moved to Old Crow 20 years ago – when she was 18 – to work with a local dog musher, spending two years there. These days her research focuses on Arctic communities and the challenges they’re facing because of climate change.

“I was back in August this year, which was the 20-year anniversary of when I first went up there, and the level of erosion along the river was really striking,” she says. “Places where the river bank is just caving in, and house-sized pieces of the river bank are just falling into the Porcupine [River] because the permafrost is melting. And you can see it particularly on southwest-facing slopes that get a lot of sunlight, so the melting has been more intense.”

Demuth says she arrived in Old Crow as a U.S. settler with no prior knowledge of Indigenous communities in the Yukon.

“I was not particularly cautious, as a young person, of the cultural differences, coming from outside into an Indigenous community,” she says. “I was naive enough that I didn’t think people would speak a different language – which, in retrospect, is kind of horrifying that I didn’t know that already.”

“I came there knowing so little about what to do – I didn’t know anything about training dogs, I didn’t know anything about hunting, I didn’t know anything about fishing at a subsistence level rather than just as a hobby,” she adds.

“I think because I was really dependent on people there to teach me everything, it put me in a very different relationship with the community than outsiders who come in. Because I wasn’t an expert, but quite the opposite – I was the student.”

“Reconciliation-driven conservation”

“We have lived a certain way in a certain type of isolation for a very, very long time,” Brandon Kyikavichik, who works as an interpreter in Old Crow, tells me. “Right now, more and more people want to come to Old Crow. And with what’s going on with the Porcupine caribou herd, we’re getting a large influx of people.” So, when it comes to the question of whether and how to allow tourists to visit Old Crow, he says “there are mixed feelings in our community.”

When I ask him about the community’s feelings toward sharing Gwich’in culture with tourists, he says, “I see tourism as an answer to a lot of our problems. But the problem is that a lot of people don’t want too many people coming to our town, and furthermore, into our traditional territory.”

The Vuntut Gwitchin government has been careful about the way visitors interact with community members for this reason. To visit Old Crow, journalists, filmmakers, researchers, and tourists must fill out an application form, providing the government with information about the purpose of their visit, the people they will be interacting with, and the perceived benefit to the community.

“I think there’s often a divide between the young and old in these small communities,” Frederick observes. “The younger people are saying, ‘Yeah, just go for it.’ And the older people tend to be more protective of their culture and tradition, and they’ll say, ‘Wait a minute, no.’”

This conversation – about tourism on Indigenous territories – is one that’s playing out across the world. In October, Parks Australia finally closed the climb up Uluru, a sacred 348-metre-high sandstone rock on the land of the Indigenous Anangu people. For decades, the Anangu had been pleading with tourists to respect the rock by simply walking around the base. But predictably, many Australian settlers and tourists were incensed to have their access to Uluru curtailed, even after years of climbers had left human waste atop the rock, which poisoned water holes and wildlife below. The dispute raised questions about whether settler tourism on Indigenous land can ever happen fairly and respectfully – especially given the long history of colonization and genocide that Indigenous peoples in both Australia and Canada have experienced at the hands of settlers.

In Canada, Indigenous people are beginning to have a little more say over the ways that tourists access their traditional territories, in what’s being called “reconciliation-driven conservation.” Rather than forcibly removing Indigenous people from the land, the newest national park in Canada, Thaidene Nëné, is co-managed by Parks Canada, the Łutsel K’e Dene, and the Northwest Territories government. A $30-million trust fund, half of which was contributed by the federal government, will pay for guardians, training, planning, research partnerships, and youth engagement, generating revenue for the Łutsel K’e Dene community. The park’s guardians are Łutsel K’e Dene rangers who monitor the health of the land and animals, and interact with tourists. The park allows Indigenous people to fish, hunt, and travel throughout it. And it ensures that the land and the sacred falls of Ts’ankui Theda aren’t under threat from encroaching uranium and diamond mines and hydropower development.

Thaidene Nëné doesn’t give the Łutsel K’e Dene full sovereignty over their land. But it may still serve as a sign that living Indigenous culture and settler tourism don’t have to be at odds. Back in Old Crow, a 2009 community planning document explained that, with respect to tourism, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation “will work with the Government of Yukon and Parks Canada to encourage the development of joint use facilities for the preservation, presentation and interpretation of regional heritage and park resources.”

“What if we weren’t eroding what makes us Gwich’in people, but we were just helping to make this a better experience for people?”

During Frederick’s time consulting with Old Crow residents on growing their tourism industry, she says community members made joint decisions through consultations with Elders about certain areas that they would not open to the public.

“I asked them, ‘Are there areas and are there things that we need to avoid discussing because they’re culturally sensitive and your Elders will not support you talking to me about them, or talking about turning them into a tourist attraction?’” Frederick says. “All of them said at the same time, ‘Yeah, it’s the caribou fences.’ That’s a hunting area that’s sacred to them. […] And I said okay, that’s good to know, because we can tell people about them.”

Most of the residents of Old Crow I spoke to, however, believed that tourism was a positive force – both for the community and for its visitors.

“We have a lot of problems with the system we live under, and there are so many abuses of justice when it comes to Indigenous people,” says Kyikavichik. “And we won’t change any of that if we don’t show them a higher state of being, and that higher state of being is achieved when we are more together – working together and doing things together.”

“We look for solutions, and solutions should always involve the betterment of everyone involved, not just the betterment of us. If tourists come up and meet the people and they see our land and hear our stories, then it helps us solidify that message that we need to be more inclusive because being more inclusive is the only way we create any kind of change in our system.”

“What if we said, you can come here, you can go berry picking, you could go with someone to check their net?” asks Kyikavichik. “What if we weren’t eroding what makes us Gwich’in people, but we were just helping to make this a better experience for people?”

The burden of reconciliation

“After residential school – that changed everything,” says Kyikavichik. “Residential school was pretty effective.”

Around the beginning of the 20th century, missionaries opened day schools in Old Crow, Forty Mile, Moosehide, and Fort Selkirk. They were soon absorbed into four residential schools established in the Yukon, the first of which opened in 1911 at Carcross. At residential schools across Canada, Indigenous students were forcibly separated from their families, language, and culture, and were physically, sexually, and mentally abused. Over 6,000 students died in them. Old Crow’s residential day school was transferred to the territorial government in 1963, with the other residential schools in the Yukon closing in the late 1970s.

“Luckily, we have our land in pristine shape. We love being out on the land, but for the most part [residential schools] killed that ancient culture that used to exist, and that’s just the way it is now,” Kyikavichik explains. Even so, many traditions, like the annual salmon and caribou harvests, persist.

When I ask whether tourism can be used to encourage conversations about reconciliation between Indigenous people and settlers, Kyikavichik hesitates.

“I still don’t know the definition of reconciliation, but what I foresee is what is always referred to as ‘reconciliation,’” he says.

“I foresee a day when we coexist in a world where tourism plays a role in our fulfilment of life and us gaining a livelihood to be able to feed our families, and a lot of our people will be able to feed their families by doing what they love: being out on the land,” he muses. “I see a situation where everything is set up by the seasons, just like it used to be in the old days. We go back to the way they did things in the ancient times.”

“But, most importantly, we educate the people from the outside on what it means, first of all, to be the Vuntut Gwitchin, and what it means to be Indigenous in general.”

“We’re looking into creating a business hub where we have one central location where we sell everybody’s arts and crafts, their sewing, and we will also have a website that will market all these products, and market the people and the stories of the people and the story of why they created that piece of art,” Kyikavichik explains.

Josie says he believes strongly in tourism as a tool for reconciliation. “It’s our own people sharing our story of our area and our history,” he says. “That’s one of the greatest reconciliations that I could ever imagine – we take people and educate them about who we are and why things are important to us.”

Demuth says while she’s grateful for the community’s openness toward teaching her, “I think it depends very much on the willingness of the community to host people, and that showing up in an Indigenous community and expecting people to teach you how to do reconciliation is a huge burden on those communities,” she says.

“If they do all of the teaching, in some ways, they do all of the homework of outsiders for them.”

On the other hand, Demuth says that having tourists visit Indigenous communities such as Old Crow helps them understand Indigenous resilience in the face of genocide and assimilation.

“I also think that it is the capacity to really recognize that Indigenous folks in Canada […] still have communities that are thriving and [are] thinking about teaching their Indigenous languages to their children and passing on the other cultural ways of life,” she says.

“I think it is very important because, at least in the U.S., there’s a tendency to erase Indigenous history from the history of the country in a way that’s destructive to contemporary Indigenous communities. But I do think that having an invitation – and not being a burden on these folks – is really important,” she adds.

As Old Crow reckons with two very different kinds of change – climate change and the influx of outsiders – the Gwich’in people are working tirelessly to protect their land and culture.

“But what I am seeing – what I’ve been foreseeing – is that change is going to happen whether we like it or not,” says Kyikavichik. “We could try to either adapt to it and prosper from it, or we can sit back and watch it happen. And I’d rather not just sit back and watch it happen.”