This article was the winner of the 2020 Northern Writing Prize.

At the very end of a peninsula, on a rocky island just down the hill from Yellowknife, lies the small First Nation of N’dilo. Built on land that once held an abundance of blueberries and moose, Yellowknife was a place where Eileen Betsina’s ancestors would gather and hunt. Betsina and her husband lived in N’dilo in a small shack by the water. They didn’t have plumbing or electricity, but that didn’t bother them – they had enough.

Betsina, a Yellowknives Dene First Nation Elder who has lived in N’dilo all her life, remembers the last time she and her husband went out on their annual fall hunting trip, spending nearly six weeks out on the land. It was the late ’80s, and Betsina was in her early 20s and pregnant with her youngest child. They left most of their belongings behind in their shack in N’dilo, taking only what they needed to survive out in the bush: blankets, pillows, a small 10-by-12-foot wall tent, and a gun.

When they returned, they found a vacant lot where their home once stood. All of their personal, irreplaceable belongings had disappeared along with it. Frantic, they began asking their neighbours what had happened to their home. They were told that the Northwest Territories Housing Corporation (NWTHC) had assumed that Betsina and her husband had abandoned their home, and as such it had been bulldozed to the ground.

Against their will, they were forced into the settlers’ economic system, even though their greatest knowledge was – and still is – how to live off the land.

“When we came back, we had no house to live in. Those guys tore our house down.” Betsina shakes her head. “I had my granny’s cast iron frying pans and everything in that house. Everything was gone. Everything. Destroyed.”

Without answers, Betsina and her family started from scratch – and they had difficulty rebuilding what was taken away from them. “We lived in a tent for about four or five months,” Betsina explains.

When they – and their new baby – could no longer weather the harsh winter in a canvas tent, they moved in with extended family. The following spring, near where Betsina’s home once stood, the NWTHC built a large house with running water, flushing toilets, electricity, and appliances, and the corporation told Betsina’s family they could live there if they paid rent.

Faced with the coming winter, Betsina felt her family had no choice but to move into the new unit. But they soon learned the house was not what they wanted in a home. While Betsina brought up their children, her husband began working odd jobs in order to keep up with the monthly rental payments and utility bills. Against their will, they were forced into the settlers’ economic system, even though their greatest knowledge was – and still is – how to live off the land.

“Archaic, colonial, and paternalistic”

The NWTHC is territorial corporation, tasked with providing safe and affordable housing for residents of the Northwest Territories. But when the NWTHC was first created in 1972, it was part of the government’s post-Second World War “northern vision,” writes historian Robert Robson. “Northern development as it occurred under the rubric of the northern vision, was a government-contrived expansionary program of resource development schemes, road building projects, military defence operations, and the introduction of government services including a variety of community development and/or re-development programs.” In other words, many Indigenous people in the NWT were forced to be dependent on a housing system that was created to control and assimilate them, part of a larger strategy to dispossess them of their land.

Today, the NWTHC maintains more than 2,400 public housing units in 30 communities across the Northwest Territories. In some communities, public housing makes up the majority of the housing stock. The NWTHC also provides financial assistance for some people who want to buy or renovate their homes, helps with emergency repairs and fuel tank replacements, and funds the building of community homeless shelters.

In other words, many Indigenous people in the NWT were forced to be dependent on a housing system that was created to control and assimilate them, part of a larger strategy to dispossess them of their land.

To help administer public housing, the NWTHC establishes Local Housing Organization (LHO) offices in communities, which are responsible for tenant relations and maintaining units. There are 73 NWTHC public housing units in the communities of N’dilo and Dettah, maintained by the Yellowknives Dene Band Housing Division. But at the end of the day, it’s the NWTHC’s central headquarters that create the policies around rent, maintenance, and evictions that the LHOs must follow.

When asked for comment, the NWTHC says that the corporation “actively seeks LHO feedback and suggestions where possible when examining or revising Public Housing policies. We also have an annual meeting with NWTHC staff and LHO managers to discuss and examine policy and other operational items.”

But Jason Snaggs, CEO of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation (YKDFN), tells a different story. “We have zero control,” he says. “These housing policies were established way back in the 1970s and ’80s. […] They are very archaic, colonial, and paternalistic. It keeps people in rent. It does not promote home ownership.” He adds, “If you make more money, you pay more rent.”

When I ask Snaggs about the NWTHC’s practice of demolishing the homes of YKDFN band members like Betsina, Snaggs replies, “There was no respect. There was no consultation.”

“In no form or fashion has housing – not just for the YKDFN but for the [entire] Northwest Territories – ever been rooted [in] or based on Indigenous culture, or tailored to the specific needs, from a socio-historical context or a geographical context, [of] the Indigenous population,” he continues.

Paying rent on your own land

Betsina and her husband didn’t own the land their home stood on in the colonial sense of the term, but as members of the YKDFN, they have the inherent right to live where they choose on the First Nation’s Traditional Territories – which includes N’dilo. It’s because of stories like Betsina’s that many Indigenous people maintain that they shouldn’t have to pay to live on their own Traditional Territories.

Most of the land in the Northwest Territories is governed by Treaties 8 and 11, and there are only two reserves in the territory – one in Salt River and the other in K’atl’Odeeche. In the late 1900s, some Dene groups began negotiating and signing new land agreements, which tend to give First Nations direct ownership over land (though the Crown retains underlying title). The Akaitcho Dene First Nations – which represents Dene from the areas of N’dilo, Dettah, Deninu Kue, and Łútsël K’é – have been negotiating an agreement on land, resources, and self-government with the federal and Northwest Territories governments for the past 20 years.

It’s because of stories like Betsina’s that many Indigenous people maintain that they shouldn’t have to pay to live on their own Traditional Territories.

In 2014, Ottawa delegated (or “devolved”) responsibility for most public land, water, and resources to the colonial Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT). Prior to devolution, the federal government managed territorial lands (most land outside communities) under the federal Territorial Lands Act, and the GNWT managed commissioner’s land (most land within residential communities) under the outdated Commissioner’s Land Act. The majority of Chief Drygeese Territory, the Traditional Territory of the YKDFN, was commissioner’s land except for the communities of N’dilo and Dettah. Those two communities lie on Indian Affairs Branch (IAB) land – Crown land set aside for Indigenous residents to use, but which no individual can own.

In order for the NWTHC to be able to build housing in Dettah and N’dilo, the YKDFN allowed land to be federally leased to the corporation. However, the YKDFN never signed the 2014 devolution and Snaggs tells me that the First Nation believes they should be receiving 100 per cent of the funding for building, maintaining, and managing the housing in Dettah and N’dilo directly from the federal government, not filtered through the GNWT.

Snaggs sighs heavily when he tells me, “The federal government’s policies are geared toward southern First Nations, which are primarily First Nations on reserve, and as a result the North has been completely neglected.”

the NWTHC’s colonial intrusion

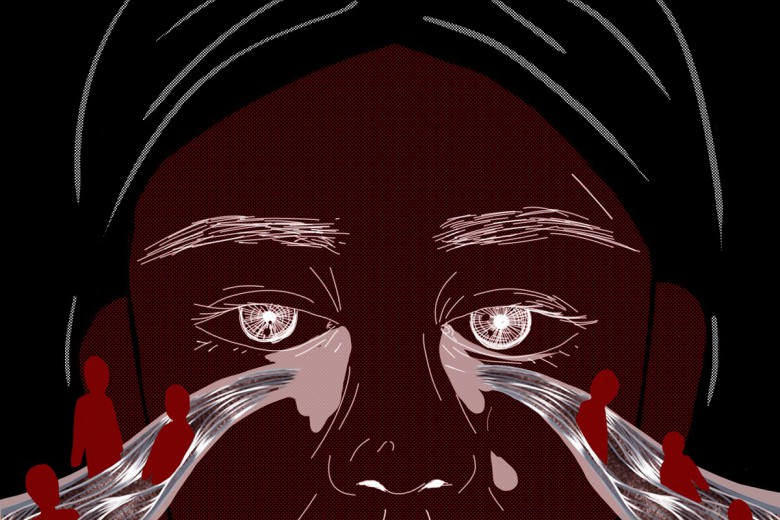

Thirty years ago, the NWTHC plunged Betsina’s family into a vicious cycle of impoverishment – one from which they’re still struggling to break free. Today, they are thousands of dollars in debt to the NWTHC because of missed rent payments. Many people living in NWTHC public housing are afraid to speak out about the injustices they face, but when Betsina tells her story, she speaks with courage.

“I’d rather live out on the land. Don’t have to pay no rent, don’t have to pay for nothing. Live free. Just live free out in the bush,” she says, shaking her head and smiling at the thought.

In We Remember the Coming of the White Man, a new book chronicling the history of the Dene People in the early 20th century, Gwich’in Elder Johnny Kaye recalls the early intrusion of the NWTHC: “As soon as they began building houses for the peoples they never asked where we would like our homes. They just went ahead, built wherever they wanted. Put us anywhere. If we complained they never recognized us, just listened and that was all. If I want to build a house on this my land, I have to pay for a lot before I can do that. I had my own log house but the Government said I had to move into a Government house and I would have to pay rent. So I moved and now I have to pay rent.”

Betsina’s and Kaye’s stories are not unique. Indigenous Northerners in public housing are often saddled with debt. Their wages are garnisheed – allowing the housing corporation to take part of their pay and put it toward clearing their debt. Even when the cost of building the house or apartment has been paid off, the NWTHC continues collecting rent on those units, even though the tenants are living on their own Traditional Territories. Tenants whose income increases by a small amount or who don’t know to report their income regularly are often charged a higher level of rent, regardless of whether or not they can afford it.

“I’d rather live out on the land. Don’t have to pay no rent, don’t have to pay for nothing. Live free. Just live free out in the bush,”

Many people across the North experience house mould, freeze up (the effects of cold weather, snow, and ice on homes), and complete disrepair, a situation they would not face if they still had the ability to live on their traditional lands on their own terms. And although Canada is close to adopting the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which includes the right to improved housing conditions, the real problem is that the Canadian government is still in control of Indigenous people’s lives, right down to the very homes in which we live.

In February 2020, member of Parliament for the Northwest Territories Michael McLeod told the House of Commons, “Forty-three per cent of all homes in Northwest Territories either have affordability, suitability, or adequacy issues. Although our government has invested significantly in housing, we know more needs to be done. There is immediate need to invest directly in housing in order to improve the lives of [I]ndigenous people in the Northwest Territories.”

Promises of improvement to the NWTHC can be found in the 2019–2022 NWTHC Action Plan. Together, the NWTHC and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) are providing $139.4 million over the next 10 years for housing initiatives. They’ve prioritized expanding the current public housing stock and repairing existing public housing.

A broken home, inside and out

Lucy Goulet and her family have been living in NWTHC public housing in her husband’s community of N’dilo since the late ’90s.

“Every time I phone housing, they ignore [me]. I know it. Maybe my number shows on their call,” she explains. “Nothing’s been changed, same old thing. My house is not a fancy house. My house is shifting lots.” Houses “shift” when the ground underneath is loose, exacerbated by melting permafrost. If a house is poorly constructed, it can lead to the house tipping, or the foundation cracking.

“Things are damaged,” Goulet adds, “like my cupboards, my floor is breaking, my door has a big gap [so] that’s why I go through too much oil in the winter.”

Goulet explains that when her family first moved in, she thought they were paying monthly mortgage payments and would eventually own the house. But they later found out they had transferred the house back to the NWTHC and were paying rent instead. “We thought this house was a mortgage, and they told us that we had signed a paper that we gave the house back. We never knew anything about it until 2014. We’re still trying to do something but it’s hard to get help. I don’t know who to ask,” explains Goulet.

Goulet and her husband have had their wages garnisheed, their income tax credits clawed back, and have been told they must pay rent every two weeks. “It’s not fair. I don’t know what happened in between those papers they said we signed,” says Goulet.

“Things are damaged, like my cupboards, my floor is breaking, my door has a big gap [so] that’s why I go through too much oil in the winter.”

Goulet doesn’t remember signing over the mortgage and agreeing to live in public housing, and she doesn’t recall the exact name of the program that she was in before the transition. In the late 1960s, the federal government started a program called the Northern Rental Purchase Program, which allowed tenants in public housing to put forward rental payments toward the purchase of their house. But only around 100 units were sold to residents through the program, and the program ended in 1987 – about a decade before Goulet moved into NWTHC housing. No such rent-to-own program exists today, though the NWTHC’s Homeownership Entry Level Program does provide support for some tenants who want to buy the unit they’re renting.

Goulet was never given the option, but if she could purchase her home outright she says she would. To make matters worse, in the midst of their struggles, Goulet’s husband fell sick with cancer in 2014 and has been fighting it ever since. Despite his inability to work, the NWTHC did not provide rent forgiveness. Goulet adds that even simple maintenance calls were not being addressed, to the point that Goulet’s husband had to do repairs himself – putting what little money they had into the home to keep it from falling down.

Goulet even went as far as taking the NWTHC to territorial court to stop the corporation from garnisheeing their wages, but that route offered little relief. Even though Goulet had gotten a second job, which meant that for many prior months she was able to pay rent on time, the judge only brought down their garnisheed wages from 50 per cent to 30 per cent.

Searching for a solution

In 2018, knowing that the NWTHC was not going to change its policies, the YKDFN began working on their own housing strategy. One of the strategy’s priorities is to allow for home ownership: “We want to be able to facilitate that process so they [members] can live in the community,” Snaggs says. Last year, YKDFN consulted with the community, asking what areas people wanted to see protected from development and what kind of structures should be built. This year the First Nation is surveying all of its members in order to assess their housing needs, explains Snaggs.

Snaggs tells me that as of November 2020, there are around 14 families on the waiting list for NWTHC housing and another four applications being processed. “This does not include applicant families who were denied or who have never applied due to the complexity of the application process,” Snaggs adds, “and it does not include the homeless, and members who wish to move back to the communities.”

Snaggs explains that the First Nation continues to request funding directly from the federal government to support the strategy. The CMHC recently announced a $13.2 billion National Housing Co-Investment Fund, which would provide federal loans to build and repair affordable housing – and $60 million of that funding is reserved for applicants from the Northwest Territories. The YKDFN is now working to find out if it can access some of the $60 million to build affordable housing.

In other words, it seems like the federal money is being used as a dangling carrot to get Indigenous governments that are part of ongoing land agreement negotiations to finalize those agreements.

When a First Nation wants to build, buy, or renovate housing on a reserve, CMHC loans can come with a ministerial loan guarantee from Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), which gives government-backed security to lenders in case a First Nation defaults on its loan. Since the policy was created decades ago, First Nations with modern self-government and comprehensive land claim agreements, like those across the North, are a grey area – if they meet the right criteria, they’re eligible for a government loan guarantee. Snaggs tell me, “If YKDFN is unable to get the ministerial loan guarantee from ISC due to the tenure of Indian Affairs Branch lands, it will be unable to access the National Housing Co-Investment Fund directly from the federal government.” In other words, it seems like the federal money is being used as a dangling carrot to get Indigenous governments that are part of ongoing land agreement negotiations to finalize those agreements.

However, the YKDFN is challenging the rule that could prevent them from accessing the National Housing Co-Investment Fund, says Snaggs. “There’s no reason that because you’re on IAB land, that a person or a First Nation who wants to build houses [and] who wants access to that funding, that that funding is not accessible to them. It is a shame that Canada fails to acknowledge Northern First Nations’ housing challenges and realities. It reeks of the prejudice and the discrimination against Indigenous Peoples that exists today, particularly in the North.”

Bringing culture home

“You hear stories of people that have been paying off homes for 40 years and the agreements just keep changing with housing so [they] always seem to be paying some sort of bill,” says Brenda Norris.

Norris is an Inupiat woman who strongly believes that Indigenous people should have the option to design and own their own culturally appropriate homes. Right now, she’s working to create a non-profit that would address the housing issues in the North.

Norris says that the non-profit will focus on home ownership for Indigenous Peoples. There are similar projects afoot across the continent – like Idle No More’s One House Many Nations project, which began by building one house in Big River First Nation and has since expanded to build energy-efficient small homes and portable units called “muskrat huts” in Opaskwayak Cree Nation and elsewhere. Those houses are built with locally sourced materials and are designed and built in part by the same people who will live in them.

“You hear stories of people that have been paying off homes for 40 years and the agreements just keep changing with housing so [they] always seem to be paying some sort of bill.”

Norris stresses that any housing solution needs to be community driven. “Before we had social housing, Indigenous Peoples lived with aunties and uncles,” she explains. Settler society calls this “overcrowding,” but these multi-generational households allow for broader and stronger networks of family support. “I think a lot of why our language is gone, for example, is because of the way housing policies are – in that mom and dad and kids live in one house, [and] granny and grandpa live in another house,” Norris continues.

“They certainly fractured the cultural way of doing things as far as taking care of each other,” she adds. “The children growing up in that kind of atmosphere lose that part of their culture – which is the inclusiveness, the sense of community that Indigenous people in the North needed to survive.” Today, many Elders live in old folks’ homes on the outskirts of the community, rarely visited by family, often passing away early because of loneliness and depression.

Norris wants to see houses designed for multi-generational households. That means “a place for family gathering, there’s a place for grandma and grandpa to stay, there’s a kitchen that opens up so you can bring a whole moose in,” she says. “So, really, an eye toward how people live culturally.”

Indigenous Northerners used to harvest their own wood from nearby forests on their land, feeding it into hearths that would warm their whole house. Now, they pay exorbitant prices for oil, propane, or electric heat. Norris points out that, these days, having a wood stove is a luxury, even though wood is the cheapest way to heat a home. “If they had that option they would save themselves a lot of money because a lot of people would go out and get their own wood as it’s a cultural thing, a land activity,” she explains.

“The children growing up in that kind of atmosphere lose that part of their culture – which is the inclusiveness, the sense of community that Indigenous people in the North needed to survive.”

When the GNWT last measured housing problems in 2014, one in five NWT households had one or more major housing problem. One survey showed that 90 per cent of homeless people in Yellowknife are Indigenous.

“A lot of these policies divided people. I really feel that’s why we have homelessness,” Norris adds. “Housing up here has a lot to do with whether or not you have a stable job, whether you have support around you to catch you when you fall. I think a lot of people – especially Indigenous Peoples in the North – are one paycheque away from being homeless. It takes housing a few months to kick them out, but if things aren’t going good, then everything falls apart – the whole family unit, everything.”

These sudden lifestyle changes have likewise magnified the trauma of residential schools. Having a housing plan that allows for traditional cultural practices would go a long way toward healing the fresh wounds of genocidal policies and Indigenous land dispossession.

Indigenous Peoples of the North have the right to reclaim their land – asserting full, non-exclusive Aboriginal Title without the underlying authority of the Crown. They have the right to live rent-free on their Traditional Territories in safe and dignified homes. They have the right to live in traditional ways, in harmony with the land. Together, it is possible to do away with government programs that only serve the needs of the Canadian state.

There is no going back to the way things once were, but we can move forward to rebuild a sense of community in homes that mix worlds, both new and old.

It’s time to make our houses home again.