nohkom only spoke her first language, nêhiyawêwin, before she left into the spirit world.

Her yellow-speckled brown eyes would recognize me during our brief quiet visits in her hospital room. “nitanis…” she would trail off while telling an important story, speaking only nêhiyawê. My heart would crack a little, fragmented, not understanding the medicine in the words of her story.

I arrived on one particular visit, when she was sitting wide awake with a container of blueberries, happy to see me. She only ate blueberries during the last journey of her physical life.

She greeted me with strong hugs, and began telling me her news in nêhiyawêwin.

With sadness in my voice, I responded, “nohkom – namoya kinistotên – nêhiyawê apsis.”

She looked so tenderly into my teary eyes, “nosim – the language is within you. Don’t forget. You will remember. micow – eat.”

Those were the last English words she said to me. It was also the last time we visited. I think about nohkom’s words, especially when I hear nêhiyawêwin speakers shaming non-nêhiyawêwin speakers for not speaking the language.

Then I remember the Old Ones’ beautiful teachings: “Language is spirit and our words are medicine.”

I was at a community gathering a few years ago that began with a Pipe Ceremony, and this was followed by teachings of Knowledge Keepers.

The first speaker began by saying, “Our spirit world only understands in nêhiyawêwin.”

Again, the shame of not being fluent swelled outside of me, flowing into tears of guilt and pain.

When I returned home, I wrote my language declaration to be fluent in prayer and conversation by the time I am 50 years old, only a few years away. When I shared the language declaration with some of my spiritual family, one responded with, “It takes four years to learn fluency.”

mâci-pekiskwetan

This began my serious language revitalizACTION.

I researched methodologies for (re)connecting to the spirit of the language, looking for the meanings within the spirit of language – specifically nêhiyawêwin, and the complexity and depth of meaning when we say “language is medicine.”

The goal of this research, titled Spirit of the Language, is to work with nêhiyawêwin teachers and learners to discuss the “spirit of the language” conceptually, to identify the causes of disconnect from the spirit of the language, and to share suggestions as to the ways to reconnect with it.

Kyle Napier and I are nîtotemak and have worked together as colleagues on past projects. I secured funding to hire Kyle as a graduate research assistant. He began a tedious literature review, looking at the laws and policies that have contributed to the disconnection between ayîsinîwak and the spirit of the language.

“Language is spirit and our words are medicine.”

After researching the disconnect from the spirit of the language, Kyle and I began reaching out to interview language warriors, educators, and learners to learn more about the spirit of the language from those who are reconnecting themselves or others to the Indigenous languages of their lineage.

The land underfoot

Spruce trees blew past on both sides, as dirt and gravel mist whirled in a torrential kilometre-long cloud behind us.

We took a vehicle with four-wheel drive, starting the journey on the potholed, construction-choked Edmonton roads and ending on the bumpy gravel reservation roads of Ministikwan 161.

If we hadn’t taken a four-by-four vehicle, we’d have been hitchhiking like my brother – whom we saw and picked up along the way.

The route allowed me to drop my brother off with my sister, who’d just had a newborn enter the world. After speaking nêhiyawêwin to my new nephew and dropping off my brother, we drove the next hour or two to Ministikwan.

We pulled up and parked, only to be greeted by an old friend whom Kyle had never met in person before.

“tânisi kiya?” Kevin asked Kyle.

kâniyâsihk Culture Camps is a year-round land-based nêhiyawêwin immersion program in Ministikwan. Kevin Lewis started kâniyâsihk with his doctoral thesis, which he’d grown and built upon throughout the years with his students.

I had adopted Kevin as my little brother when we were both doctoral students at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills. We three – Lana, Kyle, and Kevin – have all worked together on different nêhiyawêwin revitalization projects in years past, but this was the first time we would all be working on something together.

We’re all related in some way, after all.

Kyle and I were invited to sleep inside the school building, sharing the space with a few of the other mature students in the cots set aside for guests.

We introduced ourselves in nêhiyawêwin and were comforted by a blanket of stories and laughter into the night.

sâkâstênohk

The sun rose, illuminating each building at the camp. Except for the teepee, each building mostly resembled a small trapper’s cabin.

At our own time and pace from wherever we were staying – whether kâniyâsihk or Ministikwan – the two dozen of us found our way down past the east-facing teepee doors and the blooming July garden, into the communal kitchen.

Among us at kâniyâsihk Culture Camps were Elders, learners and their children, relatives, a few other academics, and members of the media.

The students would be presenting their learnings from the program since they began it nearly a year earlier. They shared their explorations through digital stories and gave workshops on topics such as art through birchbark biting, learning the language through the land, the use of flashcards for learning, familiarity and relationality with medicines and plants, and use of motion for active, full-body learning.

That evening, we held an ancestral Bear Sweat Ceremony in nêhiyawêwin. Walking up, you could smell the fire and feel the heat from the glowing asinîy-mosômak.

The first dialogue circle was held in the afternoon of the second day, after breakfast and more presentations from the learners.

Despite somehow thinking we would close the dialogue circle early, people shared their stories and contributions around pâskwâwi-nêhiyawêwin from afternoon’s daylight into the evening dusk.

Kyle and I gathered a few chairs together in a circle in the teepee, and Kyle – rather unceremoniously, but importantly – set out two digital recorders.

Those who chose to share their words passed around a small, palm-sized birchbark canoe, which was used similarly to a talking stick.

Despite somehow thinking we would close the dialogue circle early, people shared their stories and contributions around pâskwâwi-nêhiyawêwin from afternoon’s daylight into the evening dusk.

Because people took their time to answer earnestly from their heart, we ended up having to hold a second dialogue circle the next day to answer the next few questions.

nêhiyawêwin and other Indigenous languages are spiritual – and we can connect to that spirit through the language, ceremony, and the land.

Sources of disconnect

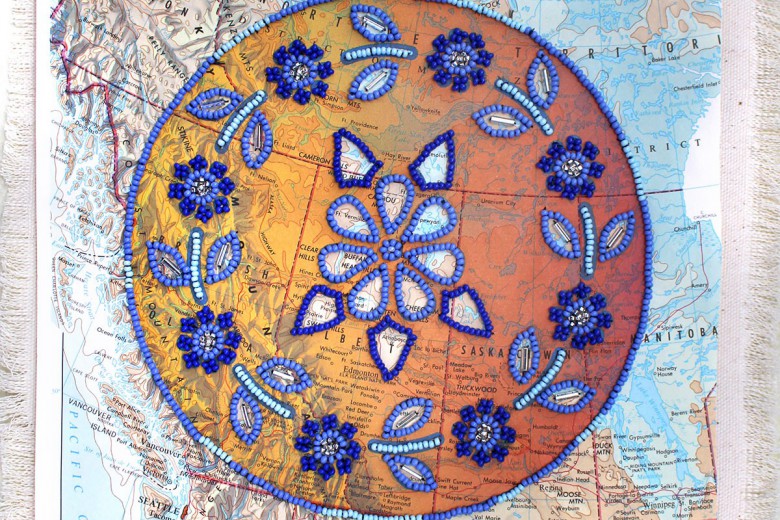

The languages are of this land, and the land holds spirit; therefore, the land is the spirit of the language.

When discussing Indigenous language revitalization, we must also acknowledge what has disconnected us from the spirit of the language in order to propose how we reconnect.

Based on Kyle’s literature review, we determined that the roots of language trauma are drawn from three main sources: colonization, Catholicism, and capitalism. The consequences include:

- massive population losses among Indigenous Peoples due to sickness and disease;

- the near-extinction of many subsistence animals on the continent due to the international fur trade and other capitalist forces;

- the governmental sway of industries and their effects on the environment; demands for power – whether through oil and gas or for electricity;

- mandated removal and relocation of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral homelands, as especially felt on reserves;

- the Indian Act’s illegalization of ceremonies such as the potlatch, the Sundance ceremony, dance, and regalia;

- the government’s further institutionalized legislation of land held by Indigenous Peoples, such as the pass system, which required Indigenous people to obtain permission from an Indian agent before leaving the reserve;

- the ongoing enfranchisement of Indigenous women to dictate assimilation through patriarchal policies and provisions maintained by Canada;

- the ongoing forced sterilization of Indigenous women, and the ongoing legacy of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Men, Boys, and Two-Spirits;

- criminalizing living on the land and not in municipalities;

- the appropriation of Indigenous languages to produce Catholic and other Christian texts in native languages;

- Indigenous children’s mandatory attendance at residential schools and “Indian day schools” on this continent;

- the ongoing removal of Indigenous children from their families into foster care through the child welfare system;

- and the compounding environmental destruction and degradation of the land, drastically impacting the ways of being for ayîsinîwak and species held in kinship.

Land Back and Language Back

Like many other Indigenous revolutionaries, it was in the years when ceremony had been banned that my great-grandfather, Mamistahp Cardinal, went into hiding deep in the bush, emboldened by his culture and language embedded in ceremony, and away from the Indian agent’s pernicious eyes.

He did this so that my grandfather, along with many others, could heal themselves and pass on the teachings to the next generations, so they could then also heal themselves in perpetuity.

ayîsinîwak hold relational kinship with the water, the land, and all our living relatives, including the Four-Legged Nation, Water Nation, Sky Nation, and Plant Nation. I think of the historical and current provincial and federal legislation – like Alberta’s Bill 1, designed to protect industry development on unceded ayîsinîwak land and criminalize those protecting their ancestral kin.

We learned that the land is integral to Indigenous language revitalization, as the land and the language are inherently and intrinsically connected.

I personally think of my disconnection to the spirit of the language via my blood relatives’ traumatic experiences when they were caught speaking nêhiyawêwin at Blue Quills Indian Residential School.

Blue Quills opened in 1931, but it has a history unlike other residential schools. In 1970, those living on reserve in St. Paul, Alberta, held a 17-day sit-in at the residential school. The sit-in worked, and by the end of the summer, ownership of the building was transferred to the Blue Quills Native Education Council.

The school, surpassing its legacy of colonization, then became the first First Nations-owned university in North America. In 2019, they changed its name to University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills.

In 2017, I graduated with my doctorate degree of iyiniw pimâtisiwin kiskeyihtamowin (ipk), or Indigenous Life Knowledge, from the University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills.

Just as we reclaimed Blue Quills in 1970, to now reclaim our Indigenous ways of being and teaching on my home reserve, we must also reclaim the land in order to strengthen our own relationship with our Indigenous languages.

I am truly humbled by the selfless gifts of knowledge that each relative shared in the interviews and dialogue circles when reflecting on the Laws of Land: kindness, truth, strength, and sharing.

Consider your own communication carefully. Do you express each word, phoneme, or non-verbal expression with love in relationality?

In all of our interviews with nêhiyawêwin-speaking Elders, learners, and teachers across Treaty 6, we learned that the land is integral to Indigenous language revitalization, as the land and the language are inherently and intrinsically connected.

The two consistent teachings that were shared are that the spirit of the language is love and that language is our connection to the land and the cosmos. The (re)connection to the spirit of the language must begin with valuing all living beings as our relatives, what we call wahkohtowin.

Consider your own communication carefully. Do you express each word, phoneme, or non-verbal expression with love in relationality?

nêhiyawêwin allows us nêhiyawak to speak in this way.

In moments when guilt and shame of language loss begin to poison my heart and mind, I sit with a bowl of blueberries, feasting on the sweet, delicious medicine my nohkom also enjoyed. I’m reinvigorated with each berry’s individual flavour, remembering my ancestors, and turning their words of encouragement into action.

“nosim – the language is within you.”