As the Saskatchewan government threatens to privatize food service delivery in provincial prisons, the response of the affected workers’ union illustrates many of the challenges facing the modern labour movement in general and public-sector unions in particular.

The province announced in January that it was issuing a request for proposals (RFP) to private vendors for contracting out the delivery of food services in Saskatchewan prisons. Seven institutions would be affected by the decision, including provincial correctional centres in Saskatoon, Regina, and Prince Albert, as well as the Paul Dojack, Kilburn Hall, and Prince Albert youth residences.

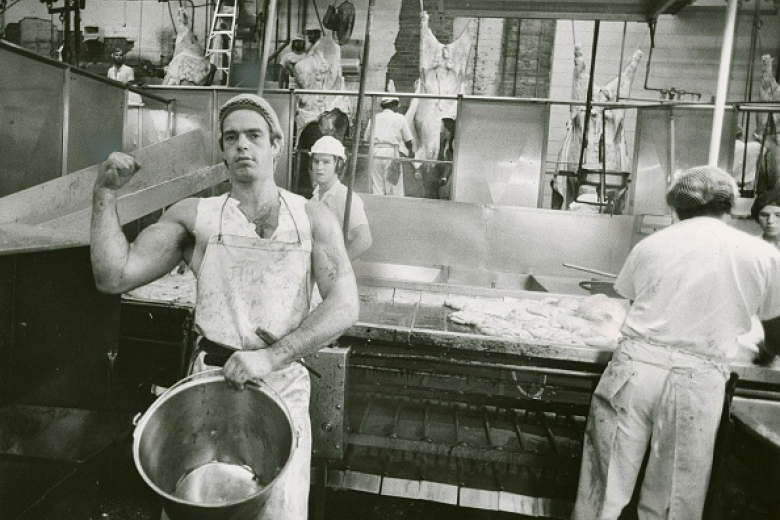

For food service workers, who are represented by the Saskatchewan Government and General Employees’ Union (SGEU), privatization poses a direct threat to their jobs. Across the province, 62 positions may be at risk, including 24 permanent full-time and 38 permanent part-time positions.

Lesley Dietz, the Ministry of Justice senior communications consultant, said the ministry issued the RFP “to determine if food services can be delivered in a more efficient manner to the facilities.” Prison food service employees were informed in January that the RFP could lead to layoff notices in the future, putting workers in a state of limbo. Dietz indicated that any ministry announcement on the outcome of the RFP would be made this fall at the earliest.

In response to the RFP, the union has undertaken a public awareness campaign to drive home the dangers of contracting out food services. Its efforts include an online petition urging people to contact their MLAs to stop privatization, as well as a paper petition circulated by the NDP opposition.

“We’ve done radio ads and a distribution of pamphlets to all households in Regina, Saskatoon, and Prince Albert via Canada Post,” says Susan Dusel, the SGEU communications manager. “So we’ve been definitely trying to raise awareness of the problems associated with privatizing corrections food services, both in terms of the cost-cutting and the safety concerns with regard to the staff as well as inmates.”

In a 2013 article for Truthdig, Chris Hedges documented the horrors associated with the contracting out of U.S. prison food services to the Aramark corporation, which included stale bread, mould, mice in the kitchen, and portions so small that prisoners were left in a constant state of hunger. Contaminated food meant vomiting and diarrhea were common among the inmates.

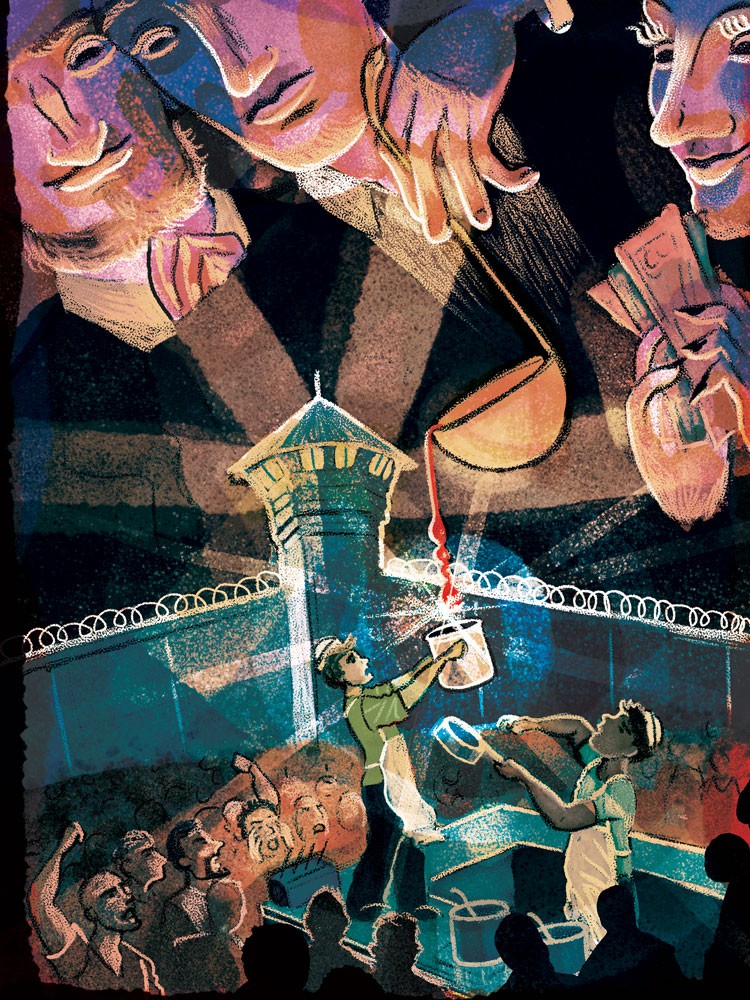

A fact sheet distributed by the SGEU details numerous instances of near-riots and violence caused by small portions, long waits, and hunger at prisons where food services were contracted out to Aramark.

If Saskatchewan privatizes prison food delivery, Dusel says that it “could be the opening of the doors to full-scale privatization within corrections.” The for-profit prison system in the U.S. entails the highest incarceration rate in the world as private corporations reap massive profits from warehousing America’s racialized underclass.

With the health and safety of both workers and prisoners at stake in Saskatchewan, the SGEU’s fight against privatization is imperative.

Thus far, however, the SGEU strategy has relied largely on appealing to political authorities, most notably through petitions to MLAs. In comments made to the Prince Albert Daily Herald early in the year, SGEU president Bob Bymoen inadvertently underscored the weakness of the union’s position by placing his hopes in the same government that is spearheading privatization and ideologically committed to dismantling public unions.

Referring to Premier Brad Wall’s admonishment of PotashCorp for laying off 440 employees, Bymoen said: “I plead with the premier to show some of the compassion for his own staff that work for him as he shows for … for the employees that work for the Potash Corporation that were laid off here a few weeks ago, when he was publicly challenging the Potash Corporation on those layoffs and asking them to be a better employer.”

At no point did Bymoen mention the possibility of strike action.

The aversion to industrial action and rank-and-file militancy is a chronic problem for trade unions in North America today, a legacy of Cold War-era anti-communism that purged the labour movement of radical activitists who had previously led workplace struggles, often with an eye toward challenging the economic system itself.

In the decades after the Second World War, the class consciousness engendered by Marxists and other radicals in the labour movement gave way to a return to what Sam Gindin, an economist and retired Canadian Auto Workers researcher, calls “sectional” unionism, which is characterized by a limited focus on bettering the conditions of discrete groups of workers (that is, the membership) rather than thinking of the working class as a whole.

For decades, such a strategy seemed viable as workers (and white men in particular) were able to improve their conditions within the confines of capitalism. But with the end of the postwar boom in the ’70s, class conflict made its inevitable return as management sought to regain its profits on the backs of workers. Neoliberalism opened the floodgates for a renewed offensive against unions, and ensuing decades saw a catastrophic collapse in unionization rates in Canada and the U.S.

Today, public-sector unions remain the last bastion of organized labour. As a result, governments have increasingly focused their anti-union attacks on the public sector through privatization and anti-union legislation. “It doesn’t appear to register with labour officialdom that the postwar compromise is dead,” said Dave Bleakney, a member of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, in last year’s Briarpatch labour roundtable. “Our liberation is not tied up in appealing to the goodwill of politicians and bosses but within ourselves.”

The organized withdrawal of labour power that we know as the strike remains a powerful tool, and the threat of using it should be openly on the table for corrections food service workers as the SGEU seeks to safeguard the livelihoods of its members and to resist the assault on working-class people more broadly.

In the event of a strike, RCMP members and upper management would likely be called in to distribute the food to prisoners like when the RCMP and private security firms were used to keep the court system functioning during the recent wildcat prison guard strike in Alberta. Just as nurses should have the right to strike to create better conditions for their patients in the long run, so should food workers be able to strike to defend the long-term nutrition and health of inmates against privatization.

Should union leaders balk at collective action, wildcat strikes are another option. SGEU members have threatened such tactics in the past, as in October 2002 when nearly 1,000 Saskatchewan correctional workers considered going on strike without the sanction of their official leadership.

The long-term success of the labour movement requires class consciousness in order to put struggles like those of prison food service workers in a larger context. Building on alliances with fellow unions such as the Canadian Union of Public Employees, the SGEU could form a broader coalition that would exert greater pressure on the government through the threat of coordinated industrial action.

But as has been seen recently in Greece, even a wave of general strikes may not be enough to change the policies of a determined anti-labour government. Thus, the defence of working-class interests must necessarily include a political element beyond labour struggles themselves.

Given the weakness of the labour movement in Canada and the continual rightward shift of the NDP, coalitions with community groups and other allies are essential if workers are to cut against the neoliberal political consensus, to identify common interests, and to build popular resistance to cutbacks and privatization. In Montreal, the Jeanne-Mance Health and Social Services Workers’ Union successfully held popular assemblies in 2011 to preserve health and social services. Perhaps such participatory and broad-based approaches are overdue out West.

The SGEU has already recognized through its media campaign the need to win public opinion to defend the jobs of corrections food workers. By building alliances capable of coordinated action and by showing its willingness to fight, the union would strengthen the hand not only of its own members but of all Saskatchewan workers.