On July 24, 2016, videos of Abdirahman Abdi’s arrest outside of his home in Ottawa surfaced on Twitter, and I watched the aftermath of police officers David Weir and Daniel Montsion senselessly beating him to death. Abdi was left face down on the pavement in full view of family, friends, and community members for 10 minutes. When paramedics arrived, they reported that his vital signs were absent and rushed him to the Ottawa Hospital in critical condition. Hours later, doctors informed his family that he had died 45 minutes before even arriving at the hospital. Abdi was a 37-year-old Somali man, unarmed, living with disabilities, and he had arrived in Canada in 2009.

Abdi’s cries for help continue to haunt me even months later. His death captured national attention because Somali community leaders, Black Lives Matter – Toronto, and other allies and supporters actively brought attention to the ongoing systemic violence against Black people, despite deflection by police spokespeople. The president of the Ottawa Police Association, Matt Skof, took to public radio to argue, “Race, in this case, is a fact, just like your age, your gender, your height. It doesn’t have anything to do with our … decision-making. Our decision-making is based on our training, and our training has nothing to do with race.” While these are not new statements made by Canada’s police services, they were startling in the face of a shared traumatic event.

In the weeks following Abdi’s death, his identities were described in various terms depending on what you read and listened to – Black here, Somali there, mentally ill here, Muslim there. Despite ongoing conversations led by activists, scholars, and community members in both public and private spheres, a connection has not been drawn between his death and the larger history of abuses committed against the Somali community in Canada.

The Somali diaspora

The contemporary Somali diaspora refers to the mass dispersal of people from the Somali territories after the 1980s, following a number of critical environmental and socio-political changes, including a significant drought and sustained political conflict. The political upheaval in the Somali territories should be understood within the context of the ongoing legacy of European colonialism, which resulted in the African independence movement of the 1960s. Mohamed Siad Barre’s presidency, from 1969–1991, and his government’s use of Soviet military assistance quickened the collapse of an already fragile state. By the late 1980s, multiple attempted coups, failing socio-political infrastructure, escalating violence, human rights abuses, and a deadly drought had displaced hundreds of thousands of Somalis. In 1990, close to a fifth of the Somali population was believed to be living outside of the country. By 1992, over 1.5 million Somalis had fled as refugees and settled across Europe, the U.S., and Canada.

Somalis arrived in Canada in three major waves: the first group arrived in the early 1970s, and the second wave in the late 1980s. According to Somali scholar Abdi Kusow, “[r]efugee statistics in Canada suggest that in 1984 there were only ten Somalis in Canada. By 1991, this figure had increased to some 12,964 individuals.” These first two waves were composed of people who were well educated and had substantial financial means. By 1996, however, after the third wave, close to 70,000 Somalis had arrived in Canada, highlighting a drastic population increase and leading to a lack of social services to properly support those fleeing civil war. The 2011 National Household Survey estimates that there are 44,995 Somalis in Canada (mostly in Ontario), though other Somali agencies put that number closer to 200,000.

Media representations of Somalis

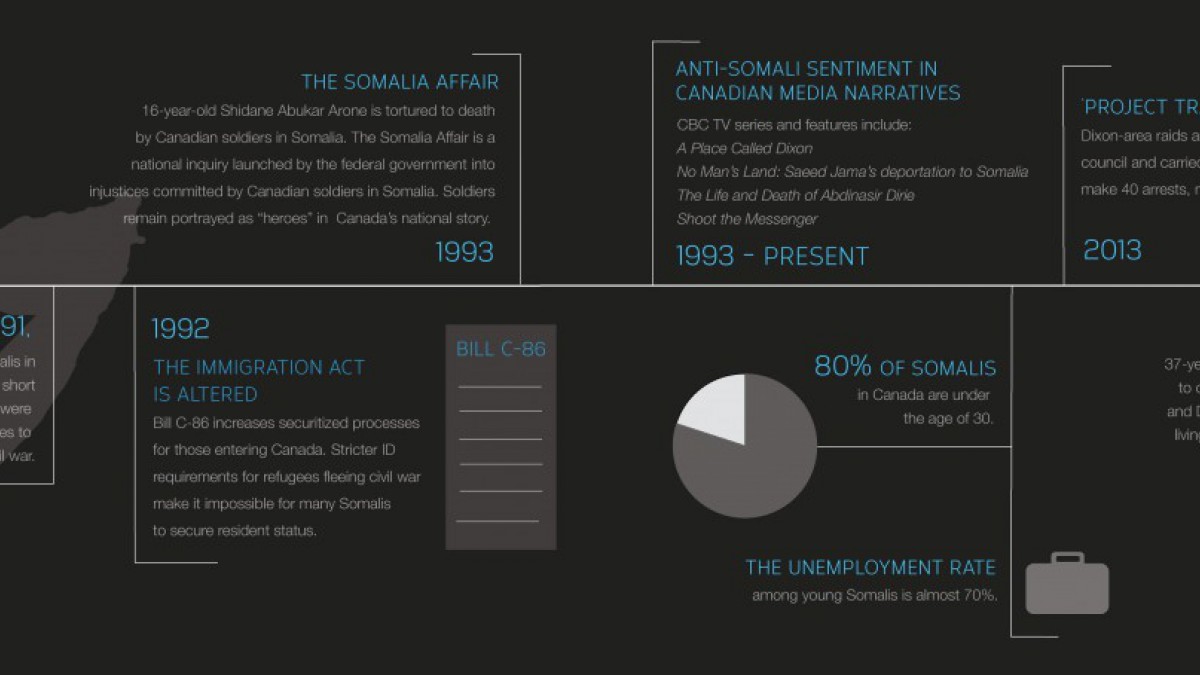

On March 16, 1993, Canadian peacekeepers stationed in Somalia tortured to death 16-year-old Shidane Abukar Arone. Twelve days earlier, Canadian soldiers shot two Somalis, killing one. After photographs, testimonies, and documentation of the violence committed by Canadian peacekeeping soldiers surfaced, the embarrassed federal government launched a national inquiry into what became known as the Somalia Affair. However, the inquiry was shut down in 1997, falling short of a full investigation. For its part, much of the national media had focused on the incongruence between the violence and the national mythos of what CBC commentator Rex Murphy called “one of the few genuinely noble enterprises of our time: Canadian peacekeeping.” As Sherene Razack writes in Dark Threats and White Knights: The Somalia Affair, Peacekeeping, and the New Imperialism, “The official story that emerged from the spectacle of the Somalia Affair – a spectacle that began with photos of the violent death of a Black man in custody and Black children bound and humiliated – was that of a gentle, peacekeeping nation betrayed by a few unscrupulous men.”

Following the Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993, when two U.S. military helicopters were shot down by Somali civilian fighters, press coverage of the war again provoked strong reactions among Canadians. These stories hit news cycles as Somalis were arriving in Canada, and the refugees were met with increasing anti-Somali sentiment in Canada’s media, which cast them as violent and uncivilized warlords, welfare bums, and nomads. The media stories that followed did little to focus on the resilience and resistance of Somalis who had fled a war and arrived in Canada with families and ambitions of their own.

Prevalent media representations, many of which have been advanced by the CBC, depict Somali youth as gang members, accessories to gangs, or terrorists. Among the CBC programs that cement these notions are the 1993 television series A Place Called Dixon; the Fifth Estate episodes “The Life and Death of Abdinasir Dirie” (2010) and “Crimes Against Humanity” (1992); the 2014 documentary on The Current, “No Man’s Land: the story of Saeed Jama’s deportation to Somalia”; and the 2016 television series Shoot the Messenger. In 2016, VICE Media also released their documentary This is Dixon.

Contemporary media portrayals of Somalis as criminals were perhaps starkest during the tenure of former Toronto mayor Rob Ford. The now-infamous leaked photo of Ford with his arms around three young Black and Arab men, which sparked the search for Ford’s crack cocaine video, saw “Project Traveller” come to a head in June 2013: police stormed an apartment building on Dixon Road in pre-dawn raids that resulted in over 40 arrests of primarily young Somali men, many of whose families expect them to be released in March 2017.

Project Traveller began in June 2012, as police started following the activities of young Somalis that police insist are organized as a gang called the Dixon City Bloods. But many Somali community members say that no such gang exists – it is a construct used by the police to criminalize, profile, and monitor Somali youth living in Rexdale neighbourhood of northwest Toronto. The mobilization of these media misrepresentations through documentaries and fictitious series has worked in collaboration with other Canadian institutions to legitimize policies that continue to have broad implications for the Somali diaspora.

Shifting legislation

With the wave of Somali refugees entering Canada in the early 1990s and the increased media reportage of the ongoing civil war, the Mulroney government introduced Bill C-86 in 1992, amending the Immigration Act of 1976. The government claimed C-86 would improve the securitization of the immigration process by ostensibly preventing immigration fraud and intercepting criminal or terrorist organizations.

Bill C-86 required that those seeking permanent residency produce identification. This posed a challenge for Somalis: Somalia had lost the infrastructure to provide ID for its departing citizens, making proper identity documents impossible to secure. Despite the Canadian government’s official stance that its strict new rules were intended only to streamline the immigration process, Lucienne Robillard, the Liberal minister of citizenship and immigration, in 1996, said in a news release, “Because they have no ID, we will not grant these people permanent resident status until they have time to demonstrate respect for the laws of Canada and for us to detect those who may be guilty of crimes against humanity or acts of terrorism.” Bill C-86 created a tiered citizenship system that affected not only Somalis, but also refugees from Afghanistan, Burundi, Sri Lanka, and Iran, continuing the legacy of picking and choosing who was a worthy candidate to become a Canadian citizen. The underlying tenor was that Somalis were not welcome in Canada, and in fact may not ever be allowed to be full Canadian citizens.

Though in 1997 the government introduced a measure called the Undocumented Convention Refugees in Canada Class, which allowed refugees from Somalia and Afghanistan who met conditions to get permanent residence status after five years, many Somalis remained in limbo, lacking the appropriate documentation to work, pursue post-secondary education, or access basic social programs to support their families. As late as last year, in conversations with Toronto-based settlement workers, many shared with me that they were still working with Somalis to secure documentation that should have been processed almost two decades earlier. The Canadian Council for Refugees has noted that the identification requirements from the 1990s have had negative long-term impacts on the ability of Somalis to access institutional resources and spaces available to Canadian citizens; in short, they could do little more than survive on the bare minimum. This has not only decreased the quality of life of many Somali-Canadians, but made it all but impossible to rebuild their lives from horrific circumstances.

Today, a large proportion of Somalis live in low-income housing; by 2013, Somali was one of the top five languages other than English spoken by residents of the Toronto Community Housing Corporation. Eighty per cent of Somalis in Canada are under the age of 30, but youth unemployment among Somalis in Toronto is about 70 per cent. As of the 2006 census, 57 per cent of Somali-Canadians lived below the low-income cut-off in 2005.

While targeted legislation is responsible for foundational obstacles, popular media representations continue to construct narratives of Somalis as inherently criminal. It becomes clear that institutions inform one another’s decisions to legitimize a shared desire to securitize Canada’s borders and police Somali neighbourhoods.

The interdependence of media and government institutions is crucial to consider in the war-on-terror age of increasing surveillance and Islamophobia. Somalis, as a relatively new refugee community in Canada, occupy a unique political space that requires them to navigate the complexity of being both Black and Muslim. While legislation continues to tighten access for those attempting to reach Canada, additional forms of control over Somali bodies are being developed.

The Anti-Terrorism Act, Bill C-51, is the newest iteration of legislative harm toward Somali communities. Bill C-51 was in part sold to Canadians by Conservatives posting on Facebook a screenshot from an Al-Shabaab video with the warning, “Jihadi terrorists are threatening Canada.” With a link leading to a petition in support of C-51, tropes of Somalis as warlords and terrorists were neatly manoeuvred back into the national imagination. This campaign, coupled with the news that Toronto police had been running a gang-prevention-program-turned-extremism-prevention-program in Toronto (in predominantly Somali neighbourhoods) for more than two years, is troubling.

Public Safety Canada has stated that community outreach and engagement is a critical part of its counterterrorism strategy; in their fifth round of funding, they distributed more than $10 million over five years as part of the Kanishka Project. Lawyer Fathima Cader notes that the RCMP’s counter violent extremism (CVE) programs are “targeted predominantly at Muslim and especially Somali communities – [to] expand counterterrorism efforts beyond law enforcement to involve civil society, including teachers, social workers and clergy. In the ways they surveil, stigmatize and harm marginalized communities, CVE programs mirror the community policing programs inflicted on broader black communities.”

The level of CVE funding used to monitor Somali communities far exceeds the numbers of Somali youth engaging in terrorist activity. In fact, Somali agencies like Midaynta Community Services, in collaboration with the Ontario government, U.S. and Canadian consulates, and other national security-based institutions, repeatedly grant CVE funding to host conferences countering youth radicalization that focus specifically on Somali communities. Meanwhile, institutional responses to the socioeconomic challenges wrought by a legacy of citizenship exclusion remain inadequate. In conversations with front-line Somali community service workers, it becomes clear that CVE is often prioritized over social programs for employment and settlement. What does this mean for a community still dealing with the ramifications of harmful legislation?

A refurbished narrative is being inscribed onto the Somali community. In the same way that Bill C-86 constructed a story of Somali warlords, Bill C-51 creates a new narrative of the Somali terrorist. The construction of the Somali body as requiring securitization has not changed in almost 25 years.

In this context, Abdirahman Abdi’s murder is not special or unique.

Looking at Somali experiences in Canada is merely a specific way to understand the manifestations of anti-Black racism and subjugation of Black communities by the Canadian state. We cannot watch the killing of Abdirahman Abdi and not understand it as a public lynching, as white supremacy remaking itself using the same logics. Our complicity is in ignoring these interlocking systems of power. We cannot afford ambiguity or simplicity – we must insist instead on specificity, examining these particular locales as a way to interrogate power.

A colleague and I have begun Project Toosoo, a high-impact media skills development program that aims to create a pipeline of youth leaders who can respond to and challenge current narratives of Somalis in Ontario. Other initiatives are taking place across Canada, alongside increasing Somali representation in a wide range of professional fields. We cannot negate the power of media institutions in shaping our legislative realities. However, we must continue to ensure that these contestations become sites from which to make calls to action. Perhaps then we will develop a clear way forward in which to disrupt existing patterns and build a world in which we can thrive.