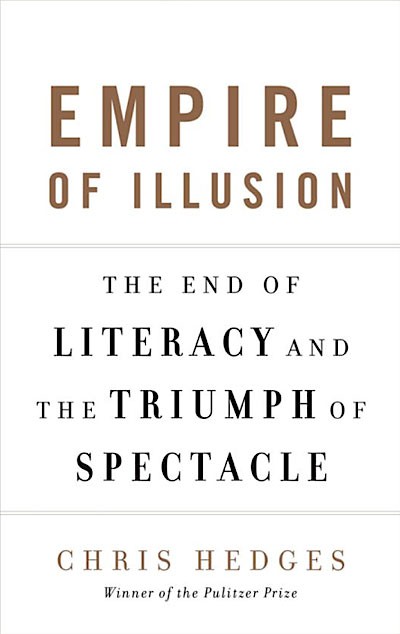

The theme of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Chris Hedges’ new book is pretty straightforward: no matter how you look at it, we’re hooped. “Our way of life is over” Hedges writes. “Our profligate consumption is finished. Our children will never have the standard of living we had. This is the bleak future. This is reality.” The good news, however, is that he looks at these desolate prospects from some awfully interesting perspectives, even if he is a bit short on solutions.

Hedges leads off strong with a provocative and original examination of professional wrestling, in which he argues that the widespread appeal of the orchestrated mayhem of pro wrestling lies in the escape it offers from a complex and terrifying reality into a realm of clearly identified good guys and bad guys. A place where Americans “can make believe everything is clear.” (While this book is a searing indictment of the failure of American society, much of it can be applied equally to Canada.) The bouts are “stylized rituals” and “public expressions of pain and a fervent longing for revenge.” In these closed arenas, real problems of unemployment, marginalization, bad relationships and shitty jobs melt away as the mainly blue-collar crowd vents its frustration through the violence meted out by their heroes in the ring.

Hedges points out that while this thirst for revenge by a powerless and fear-ridden America has always been at the heart of professional wrestling’s appeal, the nature of the villains and heroes has changed in intriguing ways. Instead of the crude stereotypes of Russian commies and Muslim terrorists such as the Iron Sheik being pitted against all-Americans like Sgt. Slaughter, the new bad guys are obnoxious Wall Street types like John Bradshaw Layfield who taunt out-of-work regular guys like Shawn Michaels, the Heartbreak Kid, who has lost everything — his home, family and job — in the recession.

But while these new dynamics reflect the real desperation in American society and even in a superficial way identify the actual class culprits, the spectacle ultimately promotes an amoral world view where cheating is the only way for the little guy to get even. It’s all rigged, is the message. There is no justice. Money is power. There is no future in organizing, no possibility of achieving justice through legitimate means.

With his reading of pro wrestling, Hedges grabs us with a fresh, engaging look at the politically anesthetizing nature of spectacle analogous to Juvenal’s famous comment about the loss of Roman civic responsibility: “Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People have abdicated our duties; for the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.”

But then we begin to see the flaw in the book that dogs it for the next 150 pages. For behind Hedges’ engaging vignettes of social collapse is a pretty pedestrian and, at times, rather tedious, analysis. Drawing on everyone from Plato to our very own John Ralston Saul, Hedges bonks us on the head repeatedly with the breaking news that “we escape the chaos of reality through fantasy.” Whether it’s the Hollywood-spawned star system or oxymoronic (and sometimes just plain moronic) “reality TV” shows, we learn, over and over, that “the fantasy of celebrity culture is not designed to simply entertain. It is designed to keep us from fighting back.” For even casual readers of Briarpatch, I don’t think this will come as a shocking revelation.

From professional wrestling, Hedges plunges us into a far darker side of American culture, pornography, to reinforce his contention that we are one sorry society. This time the rock he lifts up reveals such depravity, such inhumanity that this section makes for almost unbearable reading. While his account is genuinely shocking and horrifying, at the end we’re not much further ahead. The chapter is designed to show us how the increasingly sadistic, demeaning material being churned out has hardened us to cruelty and desensitized us to suffering, and Hedges goes so far as to link this grotesque phenomenon to America’s tolerance for high levels of incarceration, lack of gun control, inadequate health care and even “rapacious corporate capitalism.” But once again we are left only to wring our hands at both the debasement of pornography and its presumed larger social ramifications, with no solution in sight. What are we to make of all this horror?

Lack of attention to praxis aside, Hedges’ preoccupation with the most dissolute details of the pornography biz, laid out here in excruciating detail, seems overdone, almost prurient. Is Hedges just engaging in the same simplistic, voyeuristic moralizing he decries in American culture?

Hedges next takes us through a blistering critique of American post-secondary institutions (paying particular attention to the elite universities where those on the inside “see their money and their access to power as a natural extension of their talents and abilities, rather than a system that favors the privileged”); the banality and deception of the “positive psychology” movement (one of my favourite chapters); and finally an emotional screed on everything else that is wrong with America.

In this last section, we see Hedges at his best — and worst. His bleak assessment of American society is unflinching, his analysis solid and his anger and passion genuine and compelling. But these same qualities also lead him to observations that are hardly new or helpful: “The corporate power that holds the government hostage has appropriated for itself the potent symbols, language, and patriotic traditions of the state;” “The defense industry is a virus;” “There are powerful corporate entities, fearful of losing their influence and wealth, arrayed against us.” Thanks, Mr. Hedges, for confirming what we’ve suspected all along. But what are we supposed to do with all of this?Despite its flaws, readers will find much in Empire of Illusion to chew on. Hedges’ contention that Obama and his administration are incapable of fundamentally changing direction and can only “feed the beast until it dies” is sobering. His explication of the idea that the “culture of illusion” he describes so well is “robbing us of the intellectual and linguistic tools to separate illusion from truth” and his dismay at the abandonment of ethics and decency is powerful. By the end, his conclusion that “there is a vast and growing disconnect between what we say and what we do. We are blinded, enchanted, and finally enslaved by spectacle” is both chilling and convincing.

Unfortunately, readers who are searching for a way out of the morass will have to look elsewhere. Hedges’ only sop to those of us not keeping an eye out for a high bridge to jump off of is a curious (and brief) meditation on the power of love, possibly a hangover from his stint in divinity school. But as the main character in Tom Wayman’s new novel Woodstock Rising puts it (after getting flashed a peace sign from a fellow hippie determined to pass him a joint at 90 miles an hour on the L.A. freeway), “I returned it, then added the power-to-the people fist to show that peace and love were all very fine, but something more was needed to bring about the changes we all wanted.”