“I don’t even know, to this day, how we did it.”

In 1979, when she was 23, Jane Marsh took a full-time job at Canada Post. Joining the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW), Marsh – working as a sorter at the Gateway plant in Mississauga, Ontario – soon cut her teeth as a union activist. “I got involved because I needed a shop steward every day,” she says, now a vice-president of CUPW Local 626. “It was a really, horribly sexist place to work during those years.” Nepotism and unfair treatment against women ran rampant, she recalls, but sexual harassment – namely within management – was particularly pervasive. “Management would go out drinking at lunch then start chasing women down,” she says. “We were in a workplace that was poison.”

What Marsh didn’t know was that the fight to improve conditions for women at Canada Post was about to radically scale up.

When CUPW and Canada Post entered labour negotiations in mid-1980, paid maternity leave emerged as a key union demand. But as Mikhail Bjorge and Kassandra Luciuk observe in an article written for Active History, the mat leave demand was far from a niche sectoral issue – especially for those in power.

“When we were on the work floor, it was us yelling at the boss. We weren’t yelling at the union [to act]. No one was there to hold our hands. [...] We’d have sit-down strikes. We did whatever the hell we needed to, and the union supported us.”

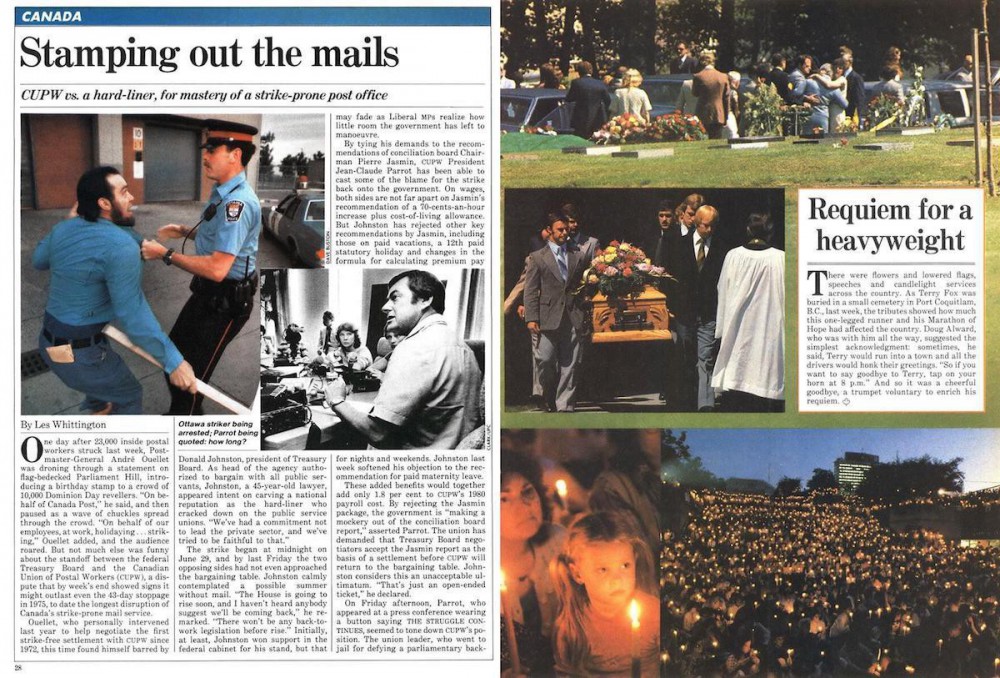

In fact, it was eyed closely by the sitting Liberal government and private sector at large. Even though the cost of paid maternity leave for CUPW members would actually be minimal, since only 1 per cent of the workforce would take it each year, both the Pierre Trudeau government and employers knew the stakes: “If Canada Post agreed to paid maternity leave,” Bjorge and Luciuk write, “then other government departments, and even the private sector, would be forced to follow suit.” Indeed, Donald Johnston, then-president of the Treasury Board (who bargained on behalf of Canada Post), pleaded with the union to drop the clause, while offering to “enable a federal task force to study its social implications” instead. “[T]he government is apparently reluctant to create a precedent among the more than 300,000 other civil servants,” Maclean’s reported, given the government’s commitment to austerity to fight growing inflation.

During negotiations, the Treasury Board refused to budge, sticking to the existing policy of six months unpaid leave, the norm across most workplaces at the time. The union, in the meantime, continued building pressure behind the demand through public education, background papers, and, significantly, alliance with the women’s movement. After an ill-fated attempt at conciliation, the union prepared to take action.

In June of 1981, with an 84 per cent strike vote, around 23,000 Canada Post workers walked out. What ensued over the next five weeks was a tough but unrelenting strike that won postal workers paid maternity leave and raised the floor for maternal benefits throughout Canada.

A vanguard fight takes off

Erupting at the onset of the 1980s, the mat leave fight was undeniably a forward-thinking one. Maternity leave had been guaranteed in 1971 when the unemployment insurance (UI) system was reformed to provide maternal benefits, but eligibility was restrictive and premiums were low. While unions in Quebec and Alberta had fought for and won agreements that forced employers to top up UI benefits years earlier, CUPW was the first national union to take the issue on in the workplace, which would naturally have a countrywide impact.

Within CUPW, a number of forces made maternity leave a priority. Women had become a significant force demographically by the 1980s, representing nearly 44 per cent of the union’s membership. But despite their growing importance to Canada Post, maternity needs were left unmet and having a child often meant job insecurity and stress. By the late 1970s, the national union recognized the issue needed fixing. It had bargained for an employer top-up in the past, but in 1980 it became a key demand. Unsurprisingly, the idea was popular with many of CUPW’s women members: “When the maternity leave issue came up,” remembers Marsh, “the women had a big discussion about it and thought, ‘This is fantastic. Women should get paid for having children.’ […] There was no reason we should suffer financially.”

While unions in Quebec and Alberta had fought for and won agreements that forced employers to top up UI benefits years earlier, CUPW was the first national union to take the issue on in the workplace.

By the time the strike broke out in June, the fight had already benefited substantially from ties forming between CUPW and the broader women’s movement. The women’s movement – namely the National Action Committee on the Status of Women – was picking up steam, increasingly influencing national debates on the issue. As researcher and professor Leslie Nichols points out, “CUPW President Jean-Claude Parrot reached out to 500 women’s groups, asking for their support and attempting to forge alliances with them.”

Support came in many forms, including “rallies, demonstrating for CUPW, holding press conferences,” as well as “[running] editorials […] and [phoning] in to talk shows to discuss the issue, helping to create greater visibility and more demand for paid maternity leave,” Nichols writes. Parrot’s leadership is not the only story, however – Nichols notes that many union members were active in both the women’s movement and CUPW and became “strategically central to the introduction of these demands and their transformation into rights.”

On the line

“We couldn’t wait for the strike date,” Marsh says. It was her first strike, and everyone was excited. At the time, Marsh had moved to a Canada Post transportation depot in a mixed-union workplace, including Letter Carrier’s Union of Canada (LCUC) members and a tiny faction of CUPW members. The depot was mostly populated by mail service couriers (MSCs), truck drivers who were mostly men and belonged to LCUC.

On the line, it was just Marsh and six other CUPW members – all women, all young, and all participating in their first strike. The seven strikers thus faced a gargantuan task: disrupt work at a shop where the majority of workers were not only not on strike, but were also men. “It was actually brutal,” Marsh remembers. “The MSCs wanted to get in [to the plant]; some were threatening to run us over if we didn’t let them in. We lied down in front of the trucks so they couldn’t move.” Things were “pretty hostile,” she says, intensified by anger from the local community. “The public was pissed off because the roads down Cawthra [Road], both ways […] there were so many trucks. They couldn’t go anywhere.”

“The MSCs wanted to get in [to the plant]; some were threatening to run us over if we didn’t let them in. We lied down in front of the trucks so they couldn’t move.”

With little CUPW presence beyond them and the occasional representative, she says that they learned their militancy on the fly: “Not one of us were shop stewards. Whatever we decided to do, we decided as a group.” And “it stopped the mail,” she says. “Completely. We were not gonna back down for anybody.” Once in a while, a steward would come by with union bulletins. Otherwise, the seven-person picket line was an island.

Following an agreement between CUPW and LCUC, the line was eventually shut down, sending the seven young unionists to Gateway. There, energy was high, the picket line full of women and “really strong activists.” Marsh describes the line surrounding the cavernous plant as completely full – a rare sight. “There was a steady line walking around the plant.”

But CUPW members were not all united in the fight. Nichols again notes that “in all 14 CUPW locals, [paid maternity leave] was controversial and led to a lot of opposition. Some men argued that they did not benefit from it, while older women articulated that they have done without and therefore did not see the importance of this provision.” Still, Marsh recalls trying to organize men, often successfully, into agreement. She would ask, “Do you have a wife, a sister, a cousin, a relative that’s a woman? That wants to go have children and has a barrier because they can’t afford to do that?”

The counterattacks mount

The outside opposition – from media, the private sector, and the government – was considerable as well. Maclean’s reported that “national attention is focused once again on the huge psychological and economic costs inflicted by an apparently interminable labor dispute that few Canadians support and even fewer understand.” The CBC called CUPW “perhaps the most unpopular union in the country” after noting that people were confused about why a strike had occurred over “fringe benefits.”

Capital, namely small business, was particularly aggrieved by the strike. Walter Carson, a business owner who headed up the Canadian Organization of Small Business (COSB), talked to Maclean’s and claimed that “6,000 to 9,000 jobs a week will be lost.” COSB members, the article reports, later showed up at a post office in Toronto to protest the CUPW picket before taking on a “hastily organized telegram blitz aimed at Ottawa.”

Meanwhile, the Treasury Board and Canada Post, with Johnston at the helm, tried to be tough negotiators and simply wait the strikers out. “Johnston has got his mandate from cabinet,” a Canada Post official told Maclean’s, “and if the postal workers want a long fight he’s going to hang them out to dry.” This tactical choice came partly from the fact that the government had recently invoked back-to-work legislation to break a postal strike in 1978. Repeating the same behaviour likely would have stoked the ire of the radical union, potentially leading to more instability, militancy, and disruption. Then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau said to the media that the government had a “clear position that we have no intention to settle this strike by legislation.” Concerned as they may have been, the government’s hands were tied.

Demands came from the Progressive Conservative Party to take away CUPW’s right to strike. But even André Ouellet, then-postmaster general of Canada Post, knew CUPW wouldn’t let the law stand in the way of a strike: “There are more illegal strikes in Canada than legal strikes,” he told the media, “and just to take away the right to strike from employees does not necessarily avoid strikes.”

Winning echoes

As Nichols observes, the allied union and women’s movement mounted a highly effective, highly visible, and, given CUPW’s membership coverage, highly national campaign. Pairing the “wider range of women” brought in by the women’s movement with far-reaching economic disruption (at a time when the federal government wouldn’t play dirty), the strike bent the Treasury Board to its will. After 42 days, the strike was over. CUPW had won.

In turn, Canada Post “agreed to pay the full amount of the employee’s wage for the first two weeks of the leave, and to top up the UI benefits for the next 15 weeks, granting their female employees 17 paid weeks of maternity leave.” Employees would get 93 cents on the dollar of their salary. They returned to work in mid-August, greeted by a headline in the New York Times that read: “Canada’s Postal Strike Ends; 6 Weeks’ Mail Awaits Sorting.”

“We were on cloud nine for months after that,” says Marsh. “In 1982, I was on maternity leave. When I went off, I got 93 per cent of my salary. The best feeling was getting it. And for everyone else in Canada [getting it], too.”

“Not one of us were shop stewards. Whatever we decided to do, we decided as a group.”

But at that time, “everyone else” just meant her fellow postal workers. “I didn’t know it was going to impact everybody,” she says. Indeed, Canada Post was just the first domino to fall. “Predictably, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers’ (CUPW) contract has touched off a storm at the bargaining table,” Maclean’s wrote.

Unions like the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) and the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) won employer top-ups soon after, in 1982. Some researchers argue that by 1992 “half of all union members in different employment sectors had gained employer-based top ups of maternity benefits.” Marsh soon noticed these trends after the strike had ended: “I went, ‘Holy cow, this had an impact on the entire country.’” Writing in 2004, Jane Pulkingham and Tanya Van Der Gaag note that “almost two-thirds of mothers with infants in their first year now access paid benefits for a median of eleven months duration and the trend is up.”

Asked what winning maternity leave means to her, Marsh is practical: it means less “pressure on your home life,” she says, “[or fear of] not being able to pay bills, or afford things. Babies are expensive. It takes an enormous amount of stress off.” She also laughs and says, “My sisters went on maternity leave, and I’d say, ‘I won you that!’”

“In 1982, I was on maternity leave. When I went off, I got 93 per cent of my salary. The best feeling was getting it. And for everyone else in Canada [getting it], too.”

As she further considers the campaign, Marsh adds: “Women picked up power after maternity.”

“After that,” she says, “women stuck together, and we became more interested in women’s rights. [The strike] started it. Maybe because we had to argue and justify why we had to have [maternity leave] to people who didn’t understand. And then it was insulting that they didn’t think we should have it.”

The confidence that came with winning – and the growth of political consciousness – also fed into another major struggle. In 1990, Marsh joined women from CUPW’s women’s committee and the women’s movement more broadly and returned to the Gateway plant to confront the managers who had sexually harassed them. “We chased down all these supervisors,” she says. “We even had a little ditty: ‘no matter how we dress, no matter where we go, yes means yes, no means no.’ They called the police.”

“That was the most powerful thing I can remember the entire time I’ve been involved in the union, because we scared the shit out of them. And it all stopped [after that].”

“No one was there to hold our hands”

Marsh returns to her experience as a new activist at the transportation depot, pointing to it as an instructional moment for the present day, when nimble shop floor action is less common. “When we were on the work floor,” she says, “it was us yelling at the boss. We weren’t yelling at the union [to act]. No one was there to hold our hands. It was us doing the yelling. We’d have sit-down strikes. We did whatever the hell we needed to, and the union supported us.”

When postal workers won paid maternity leave, they won much more. Not only did they raise the floor from coast to coast, but new activists were born and the feminist movement scored a major victory. “All this time, to maternity to now,” Marsh reflects, “it’s all [been] about security. My entire life. A secure job, a decent place to work, where people weren’t gonna harass the shit out of me – that type of thing.”