TA: Can you describe this project and situate it in the context of your previous work?

DM: For two years, I have been working with Peterborough-based Artspace curator Jonathan Lockyer on a project called Waawaashkeshi // Aanikoobijigan, for which I created two exhibitions, a hunting trip, a community feast and gathering, and an artist book. The project was informed by the 1906 arrest of my grandfather’s grandfather, Narcisse Miner, for harvesting a deer. He was a member of the Georgian Bay Métis community, which had been kicked off of Drummond Island in Lake Huron after the War of 1812. He was asserting his harvesting rights on our traditional territory, but the Crown charged him with poaching.

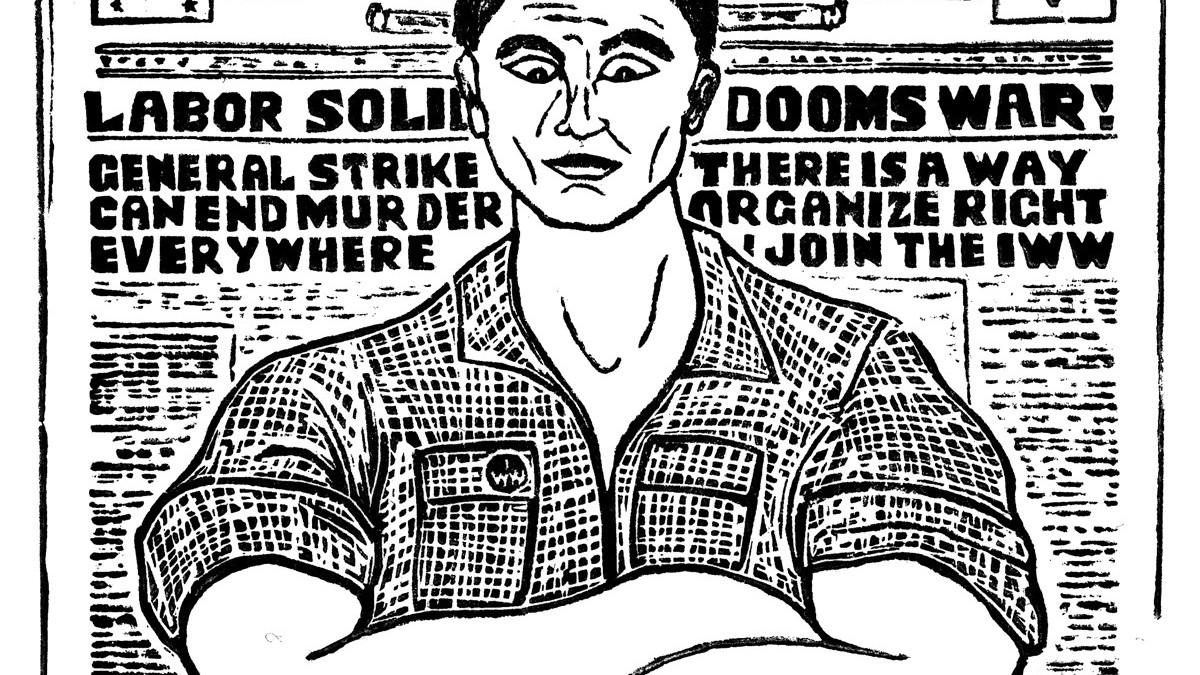

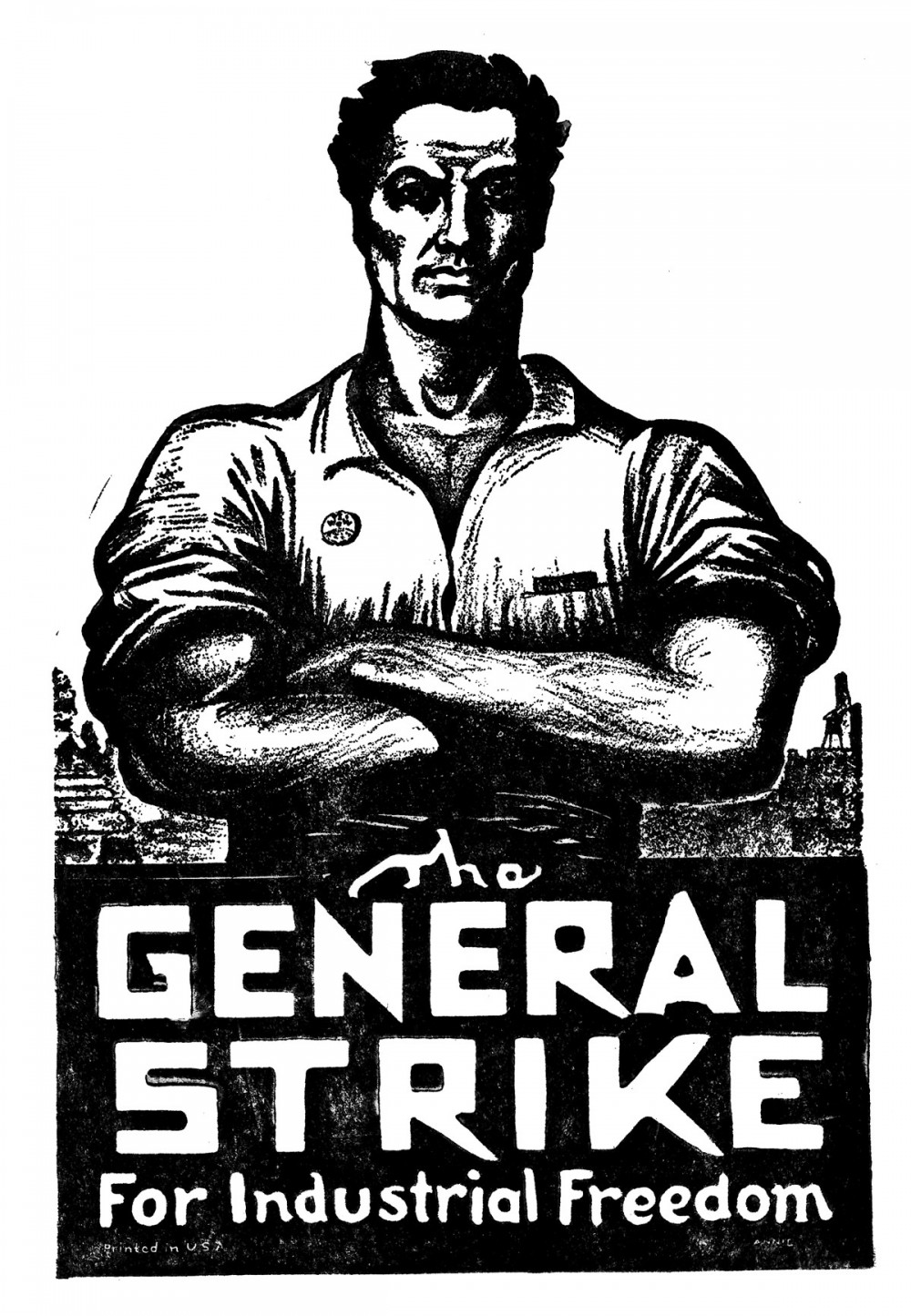

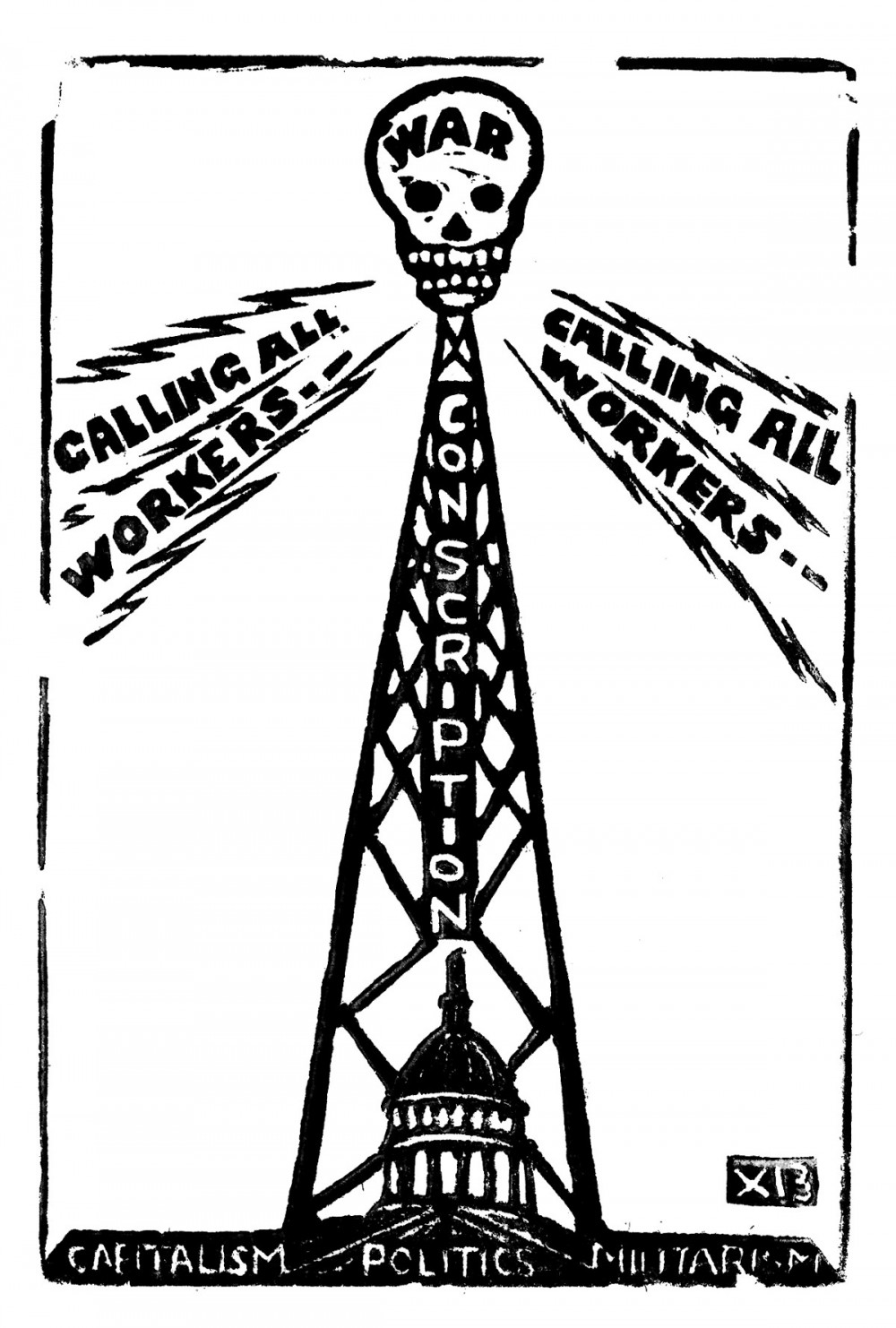

Now, in collaboration with curator Jonathan Lockyer and Trent University labour historian Bryan Palmer, I will be printing hundreds of old graphics from the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW, or Wobblies) for what I am calling the Wobbly Print Project. The graphics are on printing blocks and range from the early years of the IWW to the latter part of the 20th century. A significant number of these blocks are hand-carved linoleum mounted on wood; others are metal.

I see the Wobbly Print Project as one of collaborating with my political ancestors.

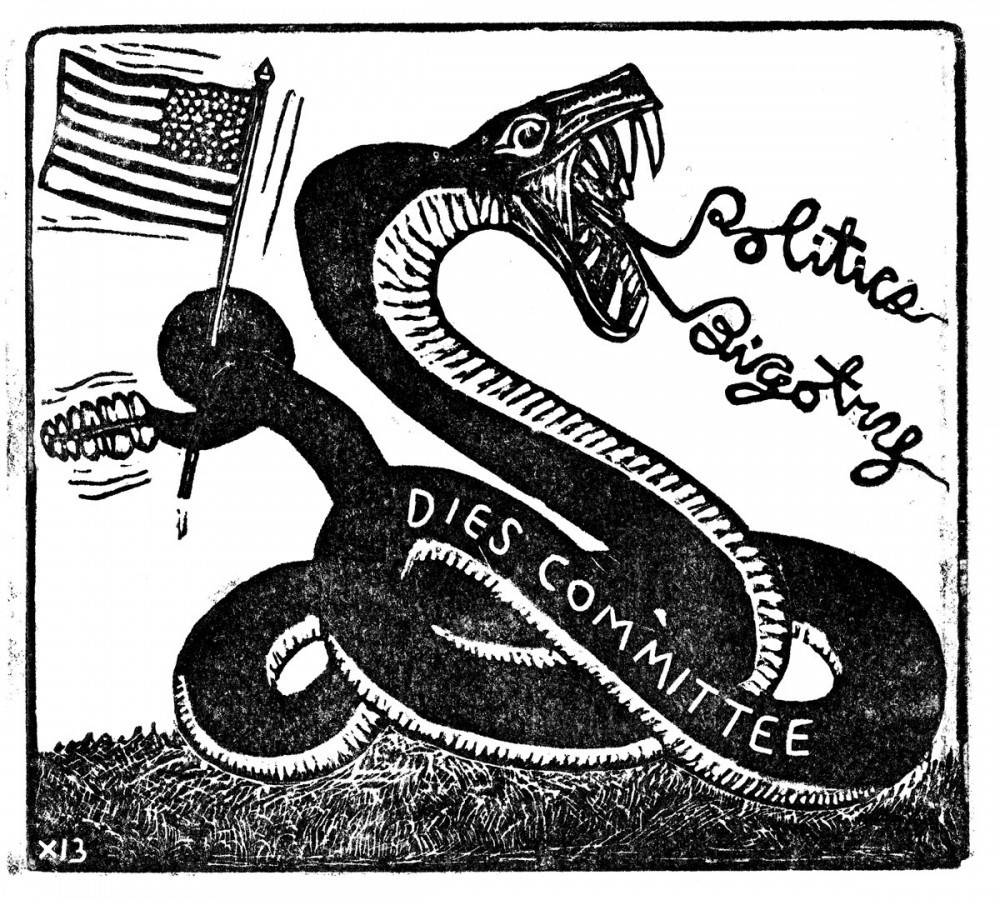

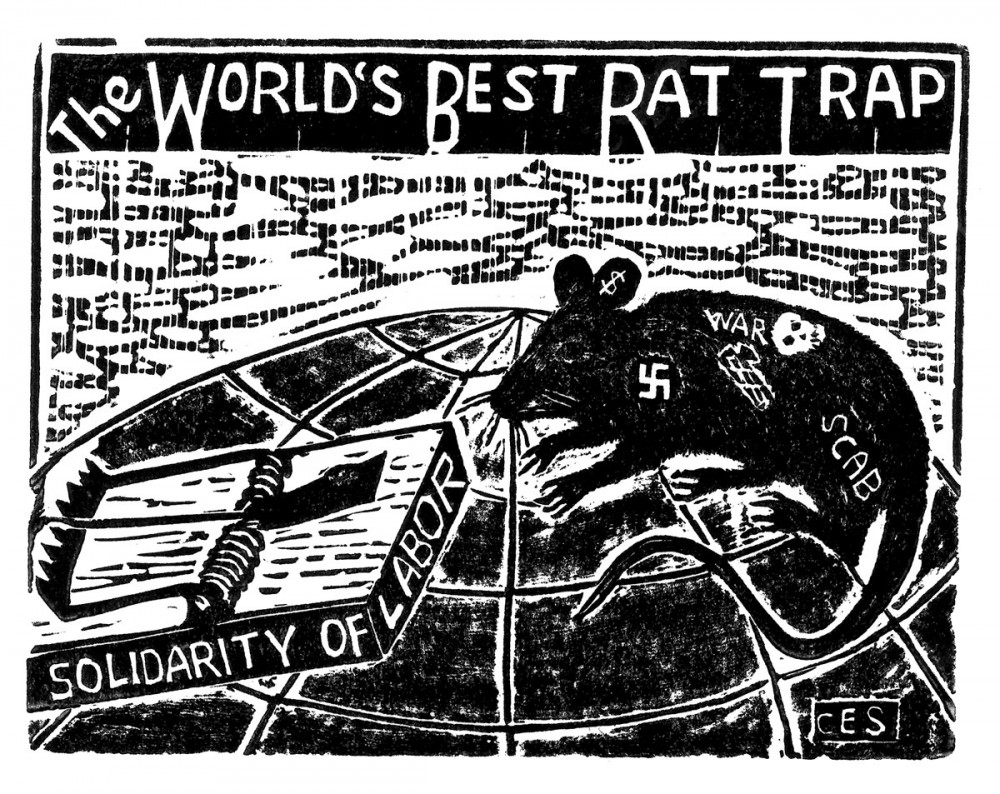

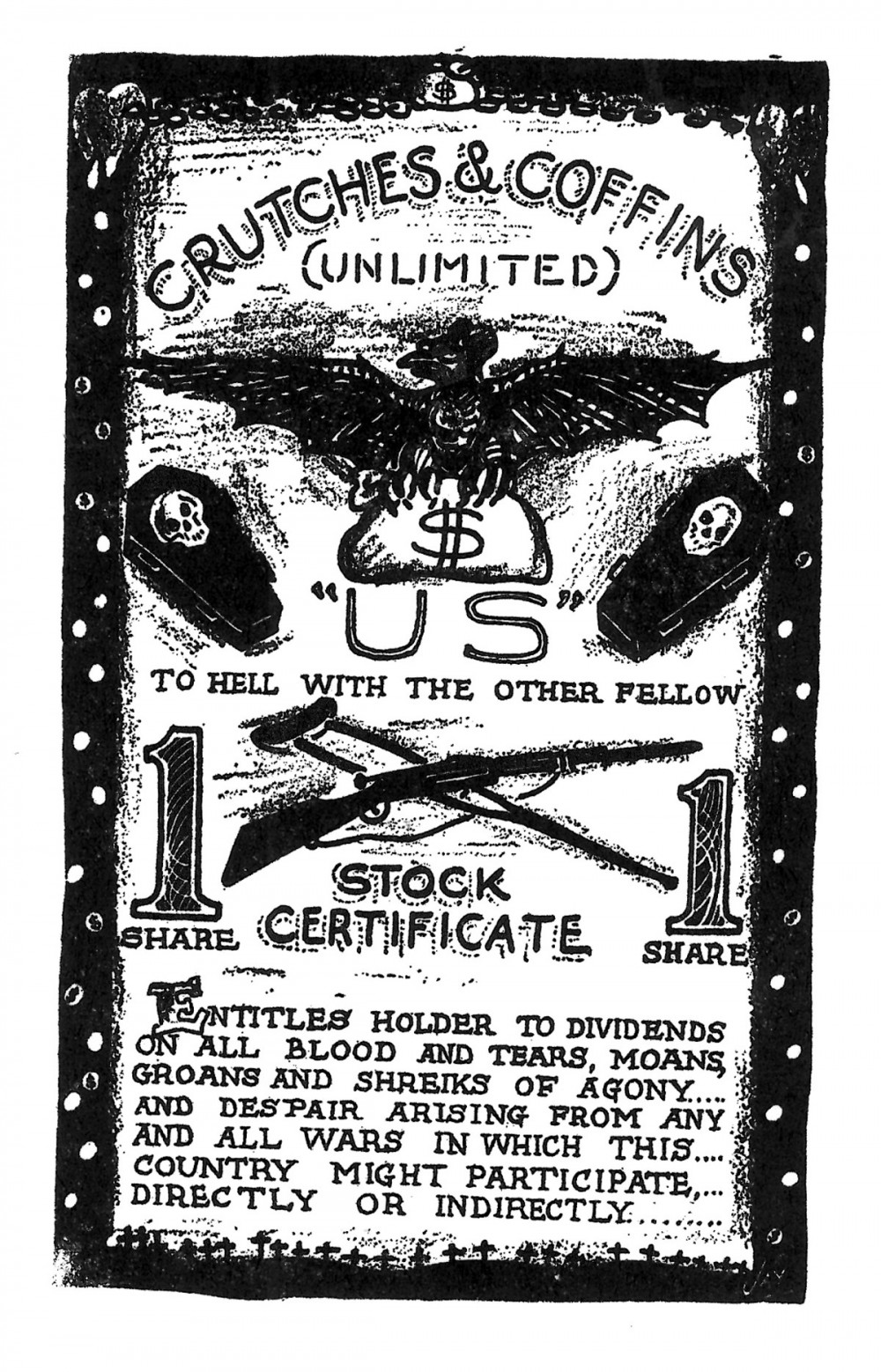

There are images by well-known Wobbly artists – Bingo, Whitey, Teddy Mason, Joe Hill, X13 or C.E. Setzer, and Carlos Cortéz Koyokuikatl. It also includes blocks from significant publications, such as mastheads from the Industrial Worker and other newspapers, the cover of the songbook for “We Have Fed You All for a Thousand Years,” and material published by the class-war prisoners incarcerated in Cook County Jail, Illinois (1917).

Currently, I have around 150 original blocks; of these, most I have never seen printed. I believe there are another 400–500 in the larger collection.

TA: How did these blocks come into your hands?

DM: You could say that I came across these blocks while collaborating with my aanikoobijiganag, a word that signifies both ancestors and descendants.

Through this intimate collaboration with my ancestors, as well as with the land, I stayed in conversation with Jon. He put me in touch with Bryan, who is a collector of rare books with an interest in radical, left, and working-class histories. A few years ago, a book dealer in Chicago had approached Bryan with these blocks and he purchased them. They have been sitting in cardboard boxes since then. Although I don’t know their full provenance – others will help fill this in – they came to Ontario from Chicago [the founding city of the IWW in 1905, and where the main office was located until 1990 and again since 2010]. It is likely that these blocks were in the basement of Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, two artists, activists, and publishers who were involved in Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., the oldest publisher of socialist and labour issues in North America.

Jon drove down from Ontario to Michigan with some of the blocks, and over the past few months, I have begun to print them. I am trying to get one impression of each image and then digitize them. Once I have printed and scanned this first group of 150 images, and with some funding for the next stage, I hope to print all of the blocks and then create a database of the images. From this larger body, we hope to curate a touring exhibition of a representative selection of the prints, and publish a book that includes new essays on the IWW.

TA: What’s your own relationship with the IWW?

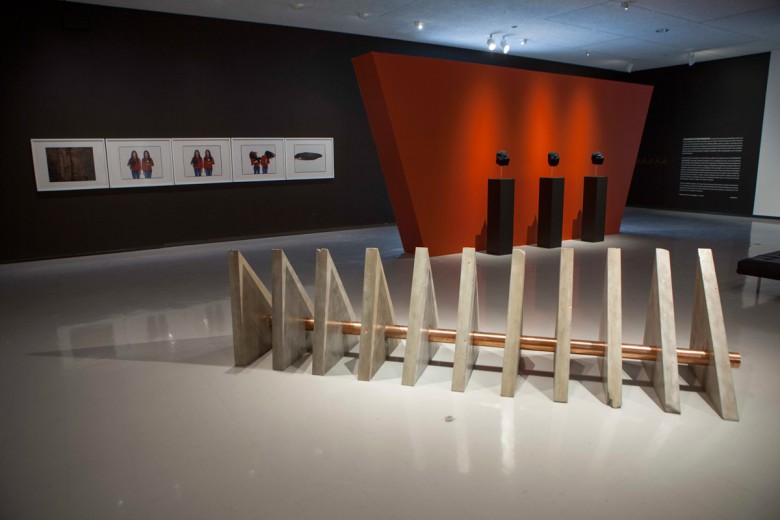

DM: During the 1990s and 2000s, I was an active member of the IWW. For the 100th anniversary of the IWW, I made a series of prints based on songs written by Wobbly martyr Joe Hill. I also published a small catalogue that was printed by IWW labour, and I contributed to Wobblies!: A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World. In 2006, I had work in “Frybread and Roses: Art of Native American Labor,” curated by Cherokee Nation painter America Meredith. This summer, I hung an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit engaging with Wobbly histories in that city.

From my perspective, the IWW is one of the most important working-class organizations on Turtle Island. The IWW had members with anarchist and socialist tendencies, but as a union, it operated (and still operates) from a heterodox and generally anti-capitalist position. Throughout the early 20th century and during the Cold War, unlike many of the craft unions, the IWW was vehemently anti-capitalist and, to some extent, pro-Indigenous. Its membership was anarchist and socialist and Marxist and syndicalist and non-partisan and anti-nationalist and anti-war.

In the early 20th century, the IWW was connected to the One Big Union and the Winnipeg General Strike. In Mexico, it was linked to the anarchist organization Partido Liberal Mexicano. The union was decimated in the 1910s when the U.S. government raided anarchist and socialist organizations in what was known as the Palmer Raids. One fallout of the raids was the destruction of much of the material culture of the Wobblies. Luckily, IWW locals documented all of the materials confiscated and destroyed by the U.S. government, so at least we know what was lost. Despite the attacks, Wobblies are still around today – they’re currently organizing workers at Whole Foods, Jimmy John’s, and Starbucks.

TA: How does art feature in the IWW and labour radicalism?

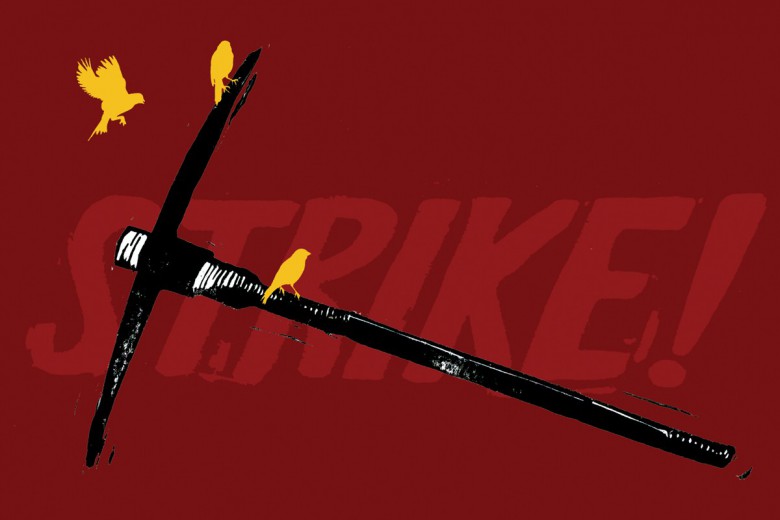

DM: Art has always been crucial for the labour movement, especially for its most radical and emancipatory sector. The Wobblies are known for using song, poetry, and the printed image to create a culture outside the control of the dominant, capitalist society. IWW graphic art would both serve as stand-alone artwork or would illustrate stories. Artworks printed as small stamps or stickers were known as “silent agitators.”

Art has always been crucial for the labour movement, especially for its most radical and emancipatory sector.

Wobbly artwork circulated in the pages of the various IWW publications, like the Industrial Worker and Solidarity. The Finnish-language publication Industrialisti was published in Duluth, MN, the same location as the Work People’s College. Chicago alone was home to 38 different IWW publications in 15 languages.

Although it’s familiar within certain communities, Wobbly art is not widely known, so the hope is that this project will make IWW art more accessible.

TA: Can you discuss some of the compelling symbolism or imagery in these blocks?

DM: Iconographically, this collection includes lots of images of humans and animals, and clear characterizations of bosses, politicians, and elites. The prints include critiques of militarism and images of groups of people working together. Setzer would often carve images of humans and animals and then put words or images on them to direct the reader toward specific readings of the image. One of his images illustrates a rattlesnake clutching an American flag near its rattle. The snake’s tongue is carved to read “politics” and “bigotry,” and the words “Dies Committee” are carved into the snake’s body, referencing the House Un-American Activities Committee that red-baited people and organizations between 1938 and 1975.

Overall, the images are anti-capitalist and pro-worker; they are anti-war and anti-hierarchy. Some were intended to be used in multiple contexts so they are a bit ambiguous. Collectively, the prints are internationalist and anti-nationalist; many are anti-government and anti-AFL-CIO [American Federation of Labor – Congress of Industrial Organizations].

What I find telling about these images is that nearly all of them contain both text and image. Even though the Wobblies were organizing precarious workers, the IWW had a culture of literacy, both in its strictest and most open sense. Wobblies critically read (and co-developed) the visual language of their own community.

TA: Can you describe the relationship between Indigenous sovereignty and the IWW? How does the IWW organize around anti-colonialism?

DM: In and around the Great Lakes and prairies, these issues commonly blend into one another. In fact, I’ve been told that Louis Riel, the great Métis revolutionary who was hanged by the Canadian settler-nation-state, met with Chicago anarchists while exiled from the prairies. In 1886, eight Chicago anarchists were convicted of conspiracy – and Albert Parsons was one of four people hanged – following the Haymarket affair. Parson’s wife was Lucía González de Parsons – commonly known as Lucy Parsons – and she was involved in founding the IWW. Although not much is known of her early life, she had Black and Indigenous ancestry, was possibly from Texas, and was a staunch proponent of Indigenous, Black, and womxn’s issues. Unlike most craft unions, the IWW always welcomed Indigenous, Black, immigrant, and womxn members.

TA: How is your practice influenced by other IWW artists?

DM: Although we only met a handful of times before his passing, I consider Carlos Cortéz Koyokuikatl my mentor – politically and aesthetically, and in the way he merged Indigenous, Latinx, and working-class issues. When I visited Chicago in my late teens and 20s, I would meet him at the Café Jumping Bean in Pilsen, the Mexican barrio in the city. After the passing of his partner, Mariana, I visited him a few times at his home. He would ask if I wanted to “make art for a living” or “make a life of art.” This way of thinking had a profound impact on me. Moreover, Carlos taught me not to make limited-edition prints. He didn’t want them to turn his artwork into “fine art” that would become inaccessible to those in his neighbourhood. Since then, as a general rule of thumb, I don’t number my work. In fact, I do not sell much of what I make; rather, I gift much of it. This also comes to me from conversations with Anishinaabeg Elders.

Visually, you can see that the work of C.E. Setzer (X13) impacted Carlos’ aesthetic practice. I have always found Setzer’s work important to my own, although before coming into this archive of Wobbly blocks I had only seen a handful of his images. So, as I print more of his work, I become more and more astonished by how impactful his style was on Carlos’ printmaking and, in turn, on my own. There is a lineage or kinship network emerging from within the history of Wobbly printmaking.

TA: Can you speak about why it’s important to you to digitize the art? How do you want this work to be used for labour organizing today?

DM: Personally, I see the Wobbly Print Project as one of collaborating with my political ancestors. As such, I want these images back in the hands of those who can use them. The Paris-based radical group Atelier Populaire saw their posters as “weapons in the service of the struggle and […] an inseparable part of it. Their rightful place is in the centers of conflict, that is to say, in the streets and on the walls of the factories.” It is likewise my hope that by printing these images again and making them accessible, they will continue to live in meaningful and transformative ways. These artworks are weapons in the service of the struggle.

TA: How can people see these blocks and support your work?

DM: As I print the images, I will begin tracing some themes. I hope that anyone – individuals or archives – with old copies of IWW publications will get in contact with me. Without knowing when each image initially appeared in print, it is hard to date most of the blocks.

People can contact me or Jonathan Lockyer about this project. I am in the process of establishing the website WobblyArt.org. We hope to get a small sample of images on the website and then acquire funding to allow us to move forward with the work. We hope that there will be interest in touring the work and doing community-based workshops, once we get to that point. I also recently started a land reclamation project and would love support in acquiring land for traditional harvesting and Indigenous knowledge-sharing.