Jacques Sauvé was the first to go down.

“It all happened so quickly and so violently that you can’t believe that such things could happen to you,” he would later tell the Montréal-matin newspaper.

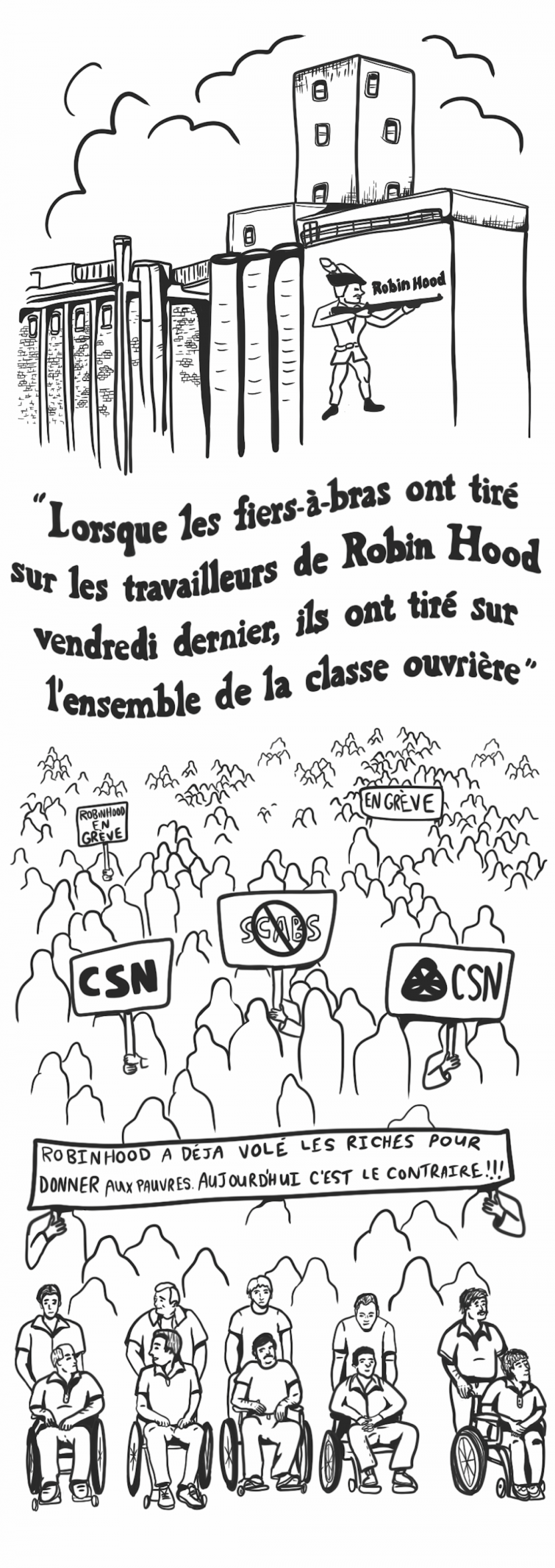

On July 22, 1977, hired security armed with shotguns opened fire on striking workers at Montreal’s Robin Hood flour mill, injuring eight workers, including Sauvé. It was the climax of a contentious strike, where the company used scab workers and private security to undermine the strikers. The public’s reaction to the violence and the outrage of the labour movement pressured the Parti Québécois (PQ) government to ban the use of scab labour in Quebec.

Today, Quebec and British Columbia are the only two jurisdictions in Canada that have anti-scab legislation. In the recent deal between the Liberals and the NDP, the NDP agreed to support the Liberals on confidence and budget matters – on the condition that the federal government would introduce anti-scab legislation. But the tale of these millers reminds us that the electoral avenue alone won’t secure gains for workers. The left and trade unions must fight to ensure this necessary protection is extended federally and isn’t cast aside by the Liberals.

Labour at a turning point

Compared to English Canada, Quebec’s labour movement has high union density and militancy. The Quiet Revolution of the 1960s emboldened Quebec’s workers and labour unions with a sort of social-democratic nationalism. As former premier Jean Lesage’s election slogan put it, the goal was to be “maîtres chez nous” – masters in our own house. In 1974, union membership in Quebec reached 41 per cent, ahead of the rest of Canada at 36 per cent.

This emboldened labour movement flexed its muscles during the 1971 La Presse strike and the 1972 Front commun general strike of public sector workers. Both strikes saw mass participation of workers and extensive use of riot police to suppress them.

The combined might of workers from different unions forced governments and employers to concede to most of the demands of the Front commun.

In the Front commun strike, 210,000 workers across Quebec walked off the job for a 10-day general strike. After the strike was declared illegal by the government, the leaders of the three major union centres were imprisoned for encouraging their members to defy the government’s decree and keep picket lines up. The combined might of workers from different unions forced governments and employers to concede to most of the demands of the Front commun.

In the 1970s, the Quebec labour movement was strong, but it was also at a turning point. How long could unions keep up this fight against governments and employers who were ready to use every tool at their disposal to stop them?

The strike begins

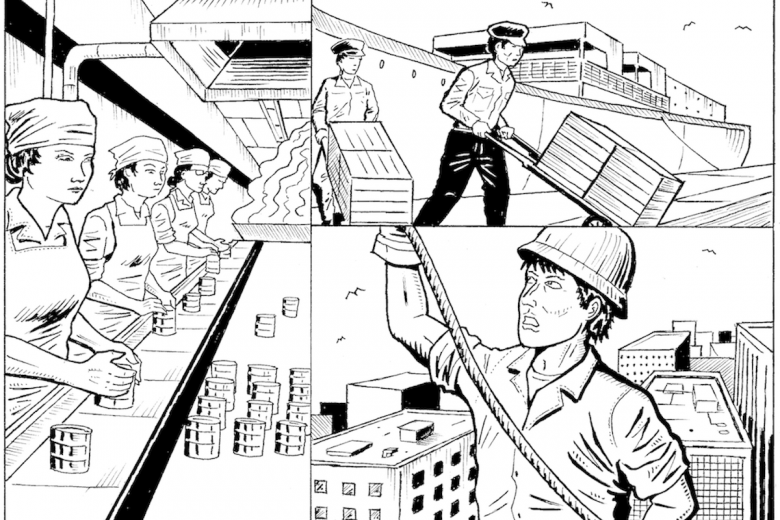

The federal Anti-Inflation Board ruled that the wage increases in the previous collective agreement between the CSN and the mills were invalid and instead demanded a 40 cent per hour wage rollback. The mills were all too happy to accept the ruling, but the CSN decided to fight back against government interference in an already settled collective agreement.

With the Trudeau government eager to prove the effectiveness of the unpopular wage controls and the public’s fears of a bread shortage, the following eight-month strike would not be easy.

They would be fighting not just the employers, but also the federal government. In a 1980 interview, CSN organizer Pierre Mercille noted that the fight was especially difficult “because we were taking on the government.” With the Trudeau government eager to prove the effectiveness of the unpopular wage controls and the public’s fears of a bread shortage, the following eight-month strike would not be easy.

Nevertheless, the millers flexed their muscles. Eighty per cent of Quebec’s flour milling capacity was disrupted by this strike.

Some Montreal grocery stores saw runs on bread in the early days of the strike: “I saw one guy walk out of here with 15 loaves of frozen bread,” Michel Durivage, assistant manager of a grocery store in the West Island, told the Montreal Gazette.

By July, the Phoenix, Ogilvie, and Maple Leaf mills reached a compromise with the CSN. Workers would take the 40 cent per hour pay rollback. However, rather than the savings being simply absorbed by the company, the funds would be invested in workers’ pensions or otherwise put in escrow until their retirement. But Robin Hood refused to compromise, keeping their mill open with the use of scab labour and firing the striking workers from their jobs.

Bringing in the scabs

Scabs – or, as they are euphemistically referred to, “replacement workers” – do the jobs of those on strike. They keep profit rolling in and undermine the strikers’ efforts, making them one of the most powerful tools in a union-buster’s kit. This is why the picket line exists: to dissuade and often physically block scabs from going to work.

Companies often employ private security both to escort scab workers into the workplace and to intimidate and harass striking workers. Robin Hood hired the Bureau des détectives industriels, a security firm run by a former wrestler named Paul Leduc. His men are described as wearing a uniform of Bermuda shorts, T-shirts, riot gear, and truncheons.

“There was no one in our gang who thought that the rifles were really loaded.”

“Well, they [private security and scabs] came through in [a] box car, three or four box cars and an engine,” says Ted Moreman, a worker at the neighbouring Stelco plant, recounting the arrival of Leduc’s men to historian Steven High. “There was one [boxcar] that was at least 20 different police on, on top of the engine with guns and machine guns and every[thing] … It was like the Old West: hanging off the cars with guns to get into the plant.”

Paul Cataldi, a replacement worker himself, recounted the picket line violence to High: “I mean, one guy [a scab] came in and he got beat up. So, [the managers] said we’re gonna get the security guys in to pick you up and drive you home. These are, you know, wrestlers, and these guys were wearing, like, leather gloves with the fingers missing, you know. And they weren’t just regular leather gloves, they were padded with lead.”

To attempt to force Robin Hood to take the same compromise the other mills had made and to hire back the strikers, the CSN leadership planned for a demonstration outside of the mill at noon on July 22, 1977. This would be the strike’s breaking point.

“Robin-Hood will pay for the bloodshed”

“There was no one in our gang who thought that the rifles were really loaded,” mill worker Sarto Emard told Maclean’s.

Two hundred workers and supporters arrived at the mill for the demonstration. The company had insisted that work continue, so they called in their private security to clear a path for trucks full of scabs. Police were on the scene but hung back, ostensibly to avoid provoking further confrontation.

Striking workers climbed the mill’s fence and threw rocks onto parked cars. To deter the strikers from approaching the mill, the security fired their shotguns at the pavement in front of the strikers. The pellets ricocheted and hit eight strikers, including Emard. He and the others were rushed to hospital.

“They didn’t use the plastic bullets, no warning shots. They just took the guns."

“I’ll never forget that fat white guy in shorts,” worker Roger Paquette told Montréal-matin. “I will always see him pointing his rifle at us. I heard several shots, maybe 15 or 20, while I was picking up my comrade off the pavement. At no time did I think of running away. I simply wanted to help a friend because he would have done the same if I had been in his place.”

Cataldi described hearing the violence from inside the mill: “They didn’t use the plastic bullets, no warning shots. They just took the guns, and these guys are hillbillies, well, shouldn’t say hillbillies, but you know, they’re wrestlers. I was inside, you know, measuring flower [sic] on the little scale and hear shooting outside and said, ‘that’s it, I’m not working anymore.’”

The labour movement’s reaction to the violence was immediate.

A Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ) bulletin titled “Robin-Hood will pay for the bloodshed” denounced the private security as “Paul Leduc’s gang of killers.”

The violence pushed the balance of power toward the union. Robin Hood had crossed a line and was forced to save face by settling, eventually reaching a new collective agreement on September 19. Even so, 55 of the 92 strikers were not rehired, 114 other jobs were cut, and some operations were transferred away from the Little Burgundy mill. The mill remains in operation today.

The legislation itself

The labour movement was unequivocal: the bloodshed demanded legislative change. As Robert Guimond put it in Vie ouvrière, a publication of the Christian labour movement, “The acts of violence of July 22, committed by private security on Robin Hood’s payroll, clearly demonstrates the insufficiencies of the current Labour Code. The employment of scabs and private security continues to limit the right to strike and will considerably reduce its exercise.”

While Robin Hood might have been the straw that broke the camel’s back, it was preceded by picket line violence at Longueuil’s United Aircraft from 1974–75 and the rioting of the Murray Hill taxi dispute of 1968–69.

The resulting legislation, Bill 45, not only included an anti-scab provision but also mandated the use of a secret ballot for union elections; guaranteed that striking workers can keep their jobs after striking; and introduced a dues check-off, which allowed unions to collect dues from all workers covered by a collective agreement.

During its rise in the 1970s, the PQ was a social-democratic party, and their leader René Lévesque’s status as a progressive firebrand propelled them to office in 1976. The PQ, with connections to the trade union movement, supported anti-scab legislation during the millers’ strike, with party members endorsing it at their May 1977 convention. The public outrage over the violence at Robin Hood gave the government the political capital to enact it.

In the words of a PQ staffer quoted in Maclean’s, “My goodness, that’s going to make people receptive to the law.”

PQ labour minister Pierre-Marc Johnson said to the Assemblée nationale, “Where there are ‘scabs,’ there is violence.”

The resulting legislation, Bill 45, not only included an anti-scab provision but also mandated the use of a secret ballot for union elections; guaranteed that striking workers can keep their jobs after striking; and introduced a dues check-off, which allowed unions to collect dues from all workers covered by a collective agreement. At the time, this was one of the largest and most worker-friendly labour law reforms in North America.

Why we need anti-scab legislation now

The enactment of anti-scab legislation in Quebec might seem like the product of a perfect storm. Workers were organized and fought like hell. A social-democratic government was in power. The public was sick of violent labour struggles. The company’s use of force backfired.

But there are striking similarities today. Inflation is approaching double digits, making life more expensive for the working class, just as it was in 1977. The Bank of Canada governor recently urged businesses not to raise wages, couching his reasoning in a wage-price spiral argument eerily similar to the justification for the elder Trudeau’s wage and price controls.

The use of scabs to break strikes persists to this day. In Edmonton, Cessco boilermakers were locked out for two years, during which time a van of scabs attempted to drive through the picket line. Without scabs, such violence would have never occurred and a collective agreement would likely have been reached much sooner. During the lockout, the Kenney government’s anti-protest legislation, Bill 32, made it illegal for picketers to block anyone from crossing a picket line.

We can’t rely on the electoral arena alone to secure gains for workers. In English Canada, only in B.C. and Ontario did NDP governments pass anti-scab legislation, and only in B.C. does it remain on the books. In Ontario, the legislation was repealed during Mike Harris’ neoliberal reforms. Today, some provincial NDP governments are hesitant to support anti-scab legislation despite being the party of labour. Even when scabs were used in the high-profile 2020 strike at Regina’s Co-op Refinery Complex, the Saskatchewan NDP waffled on supporting an anti-scab bill, with their then-Labour critic David Forbes warning against “unintended consequences.”

If anti-scab legislation is to be extended across Canada, the NDP’s best efforts and the Liberals’ reluctant co-operation might not be enough.

It’s worth noting that a federal anti-scab law would only protect federal employees and private sector workers in the few federally regulated industries like banking and railways. However, a federal law could pressure more provinces to adopt similar legislation, which would cover all other workers.

In Quebec, the reason the policy stays on the books is not because of the benevolence of successive right-wing and centrist governments, but because labour unions are organized and fight to extend and maintain it.

Over the past decade, the CSN has advocated for the Quebec Labour Code’s definition of an employer’s “establishment” to be broadened, so scabs who work remotely are banned as well. In 2021, the Tribunal administratif du travail ruled that a company’s use of remote scabs violated the Labour Code during a strike at a Joliette cement plant. While the decision is being appealed, Québec solidaire MNA Alexandre Leduc introduced a private members’ bill to the Assemblée nationale in May to codify the ruling in legislation before the appeal.

If anti-scab legislation is to be extended across Canada, the NDP’s best efforts and the Liberals’ reluctant co-operation might not be enough. This necessary law won’t be instituted or maintained unless trade unions and the left as a whole are prepared to fight for it.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)