On September 8, 2010, more than 500 people marched through Dakelh Territory in downtown Prince George, British Columbia, in a protest led by the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council against the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline project. The protest represented but one of a series of escalating actions in opposition to the proposed $5.5 billion pipeline and tanker port, which would transport bitumen from Alberta’s tar sands to the British Columbia coast at Kitimat for shipment to Pacific markets.

While the Calgary-based company has described the project as a linkage of “national strategic importance” First Nations opposing Enbridge are increasingly vocal about the threat the pipeline poses to the environments that underlie both their survival and that of all northern residents.

The Northern Gateway project consists of a proposed 1170-kilometre twin pipeline, crossing dozens of First Nations’ traditional territories as well as 785 watercourses. A smaller 20” line would ship condensate — a kerosene-like liquid used to thin heavy oil for transport — east, while a larger 36” line would transport approximately 500,000 barrels of crude bitumen to port daily.

At the Kitimat marine terminal, the pipeline would supply an estimated 225 tankers yearly. These tankers would range from the sizable Aframax vessels, carrying up to 700,000 barrels of oil, to the super-sized VLCC tankers (literally, “Very Large Crude Carrier”) carrying up to 2.3 million barrels of oil. Before reaching open waters or foreign ports, these boats would be required to navigate the treacherous Douglas Channel before heading through the Hecate Strait — the world’s fourth most dangerous watercourse, according to Environment Canada.

Treacherous watercourses

Coastal First Nations know the unpredictable violence of these watercourses from both personal experience and multi-generational oral history. The memory and effects of the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill, which dumped 257,000 to 750,000 barrels of crude oil just north in Alaska, also linger in the region after over two decades. That spill occurred in Prince William Sound, which U.S. Coast Guard Admiral Paul Yost described at the time of the spill as “not a treacherous area.” In contrast, the malevolent waters of the Douglas Channel and Hecate Strait are difficult to navigate and even harder to clean if an accident were to occur.

Leaders of Coastal First Nations, a coalition of nine First Nations from the north and central coast, travelled to Louisiana after the BP spill into the Gulf last summer to witness the new technologies developed to handle a spill in a marine environment. Gerald Amos, president of Coastal First Nations, reported that “despite massive investments in new technologies to extract oil from the earth, there appears to be no advance in our capacity to cleanly remove oil from water.”

Although much of the oil had visually disappeared by summer’s end, an August report from five oceanographic experts concluded that 79 per cent of the oil released by the BP disaster remained present in the ecosystem and a serious threat.

While thousands of dead fish and birds — as well as economic losses to spill-impacted fisheries measuring in the billions of dollars — continue to accumulate, we are still learning the long-term impacts of oil spills in marine environments. But the clearest lesson is one from grade school: oil and water do not mix. With this in mind, Coastal First Nations declared a moratorium on oil tanker traffic in their traditional territories in March 2010.

“The dinner plate of the people”

Gerald Amos, an elected councillor with the Haisla First Nation and traditional name holder as well as the president of Coastal First Nations, spoke to Briarpatch from his home in the Haisla village of Kitamaat. Living four or five kilometres from the proposed oil terminal, he described his concerns about the introduction of tankers to the area.

Holding the name Gaadakhak within the Beaver Clan, Amos recounted his people’s long-standing connection to their territories. To his people, Hatlalisna, the place where the lower reaches of the Kitimat River meet the ocean in Douglas Channel, mixing fresh and salt water, is not a convenient place to load oil onto tankers. “In the old days this was the dinner plate of the people. It sustained us for thousands of years.”

Industrial development, however, has endangered both the environment and traditions of the Haisla First Nation. The development of Kitimat over the last 60 years, driven by Alcan’s aluminum smelter (now owned by Rio Tinto) and Eurocan’s pulp mill, has decimated local food resources. According to Amos, “there has been an advisory warning on local crabs for 25 years. People don’t eat crab now because they are polluted and dangerous to your health.”

Although Eurocan has now closed and the smelting plant is modernizing, a new oil pipeline and tanker port threatens to undermine the prospects for ecological restoration and cultural revitalization. According to Amos, “additional [tanker] traffic, even without a spill, would impact resources.”

Thus, the Coastal First Nations, alongside and in coordination with their member communities, have been working on a number of fronts to protect their territories. This includes making their case before the Joint Review Panel and working with legal counsel to ensure their rights and title are respected, and extends to direct action. Amos was clear: “people will do whatever it takes to see their interest in the lands and seas respected.” While some may refer to this as civil disobedience, Amos prefers to call it “civil obedience” or “following the Nuyem.”

“The Nuyem are our traditional laws, and people standing on the line are simply being obedient to how they have been taught” Amos explained. “Nuyem, in its simplest terms, teaches us that we are all culpable for where the earth is at. We need to take responsibility for our activities, for climate change. As children, the first part of the Nuyem we learned was about respecting the weakest creatures. We were taught that you are not separate from your environment, and that you need to respect that.”

A vital connection

Living several hundred kilometres inland, the communities of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council possess a deep relationship to their own storied landscape. In their own language, the Carrier refer to themselves as Dakelh, meaning “people who travel upon water.” Bounded to the east by the Rocky Mountains, to the north by the Omineca Mountains, and to the west by the Coast Mountains, their territories are spotted with numerous natural lakes and wetlands, as well as man-made reservoirs. Their lakes and streams host an abundance of fish, including resident trout, char, sturgeon and whitefish, as well as the cyclic returns of the anadromous salmon to spawn in the waters of their birth.

Approximately 340 kilometres of Carrier Sekani lands would be bisected by the Northern Gateway pipeline route, roughly 30 per cent of the total length of the proposed pipeline. In the Carrier Sekani Declaration, issued on April 15, 1982, they proclaimed “we of the Carrier and Sekani Tribes have been, since time immemorial, the original owners, occupants and users of the north central part of what is now called the province of British Columbia. [” ] [I]n addition to the original ownership, occupancy and use, we have exercised jurisdiction as a sovereign people over the said lands.” Enbridge’s pipeline threatens the vital connection between Carrier Sekani people and their territories.

Like the Haisla, the impacts of development are not unknown to the Carrier Sekani. In fact, Dakelh and Haisla communities have already been linked by the devastating impacts of a major energy project. The construction of the Kenney Dam in the 1950s fundamentally altered the geography of Carrier Sekani territories, strangling the Nechako’s eastward flow and redirecting the majority of its water backwards through a 16-kilometre tunnel in the Coast Mountains to provide power for the Alcan smelter at Kitimat.

Originally developing from its headwaters in the Coast Mountains and flowing east, the Nechako was once the most important tributary of the Fraser River. The name of the Nechako River is taken from the Dakelh word, Necha-Koh, meaning “river in the distance.” However, the dam not only led to extensive flooding of Dakelh lands, but also ensured the majority of the “˜distant’ waters never arrived as it reduced the Nechako’s eastward flow by 75 per cent.

The reduction in flow made the Nechako River far more susceptible to fluctuations in river temperatures, altering the viability of fish in the river. Salmon stocks are down, and the Nechako white sturgeon, a genetically unique species to the area, is seriously endangered. According to David Luggi, Tribal Chief of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, “only 400 are left today, down from roughly 4,000 in the sixties.”

While the Carrier Sekani traditionally harvested fish for food, social, and ceremonial uses throughout the year, they have self-imposed restrictions to attempt to conserve particular salmon stocks and the white sturgeon. But they fear the potential impacts of the proposed pipeline on vulnerable fish stocks.

Even the relatively minor impacts of water temperature increases from clearing vegetation at pipeline river crossings could further endanger the survival of these fish, although the biggest concern surrounds the potential for a spill. As pipelines are not invincible, Luggi states, “it is only a matter of time before a rupture occurs.” According to a National Energy Board report, there is an average of one rupture every 16 years for every 1,000 kilometres of pipeline in Canada.

Serving to punctuate this point, just prior to the beginning of the Joint Review Panel process for the Northern Gateway proposal, a breach in another Enbridge pipeline in Michigan’s Kalamazoo county released an estimated three million litres of oil. Despite Enbridge’s claims to instantaneous response and infallible monitoring, it took 18 hours after the alarms were first triggered for the spill to be located — not by Enbridge employees, but by locals.

Compared to much of the proposed Northern Gateway route, Michigan is relatively even terrain and far more populous. What happens when the break is in a remote, mountainous region, where the pipeline could be buried beneath five feet of snow? Mountainous terrain makes the line not only inaccessible, but also raises the risk of a landslide rupturing the line. The environmental and cultural consequences of such a spill would be devastating.

After the Northern Gateway project was first proposed in 2005, the Carrier Sekani conducted research with elders in their communities to discuss the potential impacts. “It’s our culture right there” explains elder Donald Prince from the Dakelh community of Nak’azdli in their published study. “Our history, way of life, culture and traditions is going to go floating down that river with the oil. We can’t just stop and say “˜I guess we’ll try a different way of life now.’ We’ve been doing this for centuries.”

Rubber stamp approval

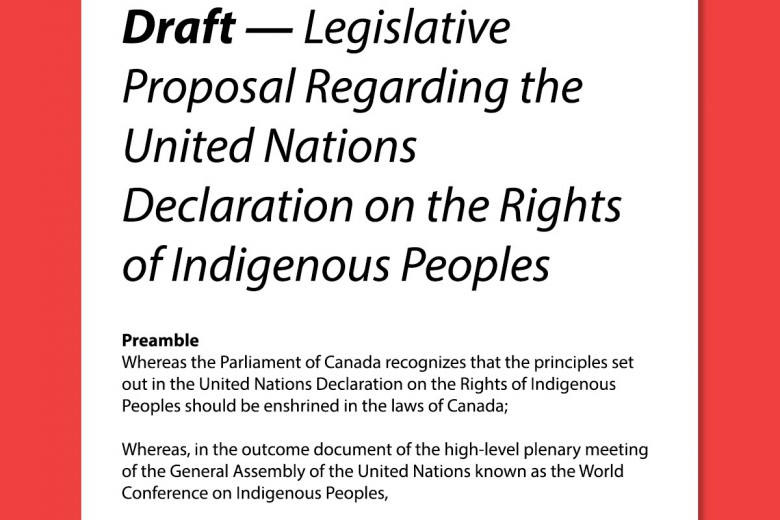

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples speaks of the necessity of attaining free, prior and informed consent from First Nations for a project that significantly impacts their rights and title. Beyond simply suggesting mitigation strategies, the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council wants the government to recognize their right to say no to developments that undermine their territories and culture. Canada recently endorsed the declaration, but added the proviso that they only endorsed it so far as it coincided with their policies and law. As Carrier Sekani Vice Chief, Terry Tegee, describes, “basically, they act like their processes trump international law.”

But the Carrier Sekani assert otherwise, vehemently defending the terms of the UN Declaration and asserting their power to determine what happens on their territories. The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council and its member communities are boycotting the federal Joint Review Panel process, refusing to participate in what Tribal Chief Luggi asserts is a “rubber stamp approval process.” On the basis that the federally appointed Joint Review Panel “has no mandate to address Aboriginal title and rights and fails to meet international standards” Vice Chief Tegee argues the federal regulators need to conduct a community-led review process grounded in internationally recognized Indigenous rights.

They also press that the review process must address the broader cumulative impacts of development, another key gap in the governing federal process. Currently, the government review of the pipeline is disconnected from an examination of the legacy of earlier energy developments, such as the Kenny Dam and Alcan smelter.

The federal review also fails to ask crucial questions about the expansion of the climatic catastrophe that is the Alberta tar sands. A recent Pembina Institute report indicates that approval of the Northern Gateway and Keystone pipelines would create the infrastructure for a 41 per cent increase in the tar sands, one of the world’s dirtiest energy sources. But for the government, these upstream impacts and climatic concerns are out of scope, as are the downstream watershed impacts. Instead, the focus is limited to impacts along the pipeline corridor.

Impacted communities, however, are making connections. Carrier Sekani communities are working in concert with First Nations directly impacted by the tar sands. They are also making linkages with First Nations communities downstream from the pipeline and along the coast who would be impacted by potential leaks. On December 2, 2010, 61 First Nations, including the majority of the First Nations in the Fraser watershed, cosigned a declaration that the Northern Gateway pipeline is not allowed in their territories according to their ancestral laws.

“Our lands and waters are not for sale, not at any price” said Chief Larry Nooski of Nadleh Whut’en First Nation, a Dakelh community signatory to the declaration. When his community gathered in April 2008, Nooski described the outcome as a consensus: “We don’t want to have anything to do with the Enbridge pipeline through our territory.” Nadleh Whut’en concerns about the salmon resonated with other communities, and the common need to protect the waters transcended cultural differences and old rivalries as communities banded together against “the risk of oil spills for decades to come.”

Dakelh communities are forging alliances to develop a multi-pronged approach to defending their lands. Their declaration served as but one in a series of actions designed to place pressure on Enbridge and its shareholders, and demonstrate that without First Nations’ consent this project is not viable. First Nations are also linking with networks of environmental activists to take the fight to banks like RBC that are underwriting tar sands and pipeline development. “We have not relinquished our powers to protect our lands for future generations,” said Carrier Sekani Tribal Chief David Luggi. “We will continue to fight and stop this project.”