July 17 at the Unist’ot’en Settlement Camp 60 kilometres south of Houston, B.C. started as a normal day up until the moment that the alarm at the bridge sounded. We had gathered for morning circle, said a prayer to bless the food, and were just in the process of sitting down to eat. I immediately got up and headed towards the bridge. Moments later I found myself face-face with Sargeant Rose, head of the Houston RCMP detachment.

More about that in a bit. First let’s catch you up a bit on the context.

For the past five years the Unist’ot’en have maintained a camp on their traditional territory in order to protect it from pipeline development. In that time the Unist’ot’en Camp has grown from a single cabin to a community of interconnected structures including a traditional pithouse, permaculuture garden, a bunkhouse for supporters, and a Healing Centre currently under construction. It has become the full-time home of Freda Huson, spokesperson for her clan, and is visited often by her chiefs and family members.

The camp is located on the bank of the Wedzin Kwa, known to colonial society as the Morice River. The bridge that crosses over to the camp is the only road access into or out of the territory, a bottleneck for would be trespassers. To enter the territory, visitors undergo a Free, Prior, and Informed Consent protocol with the Unist’ot’en. Most people who come with respect and friendship are admitted. Even the forestry industry has been required to send their bosses out and modify their practices in order to continue work on the territory. Pipeline workers who have tried to sneak into the territory have been intercepted and evicted.

Beyond the issue of pipelines, the Unist’ot’en project is about re-occupying the lands they were forcibly evicted from by the colonial Canadian state. Keeping up with their cultural practices is just as important as stopping the pipelines. The Unist’ot’en have never stopped hunting, fishing, trapping, and picking berries on their territories. Many of the Elders cannot stay out for long periods of time, but they visit frequently and tell stories about the land. In particular they refer to the message they were given by their grandmother, the late chief Christine Holland, who taught them their culture and made them promise to protect the land and never sell it.

Back to the present story. Toe to toe with Sgt. Rose. He’s telling me he needs to speak with Freda. I’m telling him he needs to wait and do protocol. This conversation loops for a while, until thankfully Freda arrives and tactfully leads the police officers back to the middle of the bridge. The conversation that followed was recorded and made into a video that went viral, once again bringing world-wide attention to the camp.

Days later, on July 23, four representatives from Chevron arrived at the bridge with an obviously staged attempt to ask permission to access the territory. In a mechanical, rehearsed speech, the Chevron agents asked to be allowed on to the territory to work. They were denied. Their “offering” of a case of Nestlé bottled water, perhaps the most bizarre element of the whole affair, was also rejected.

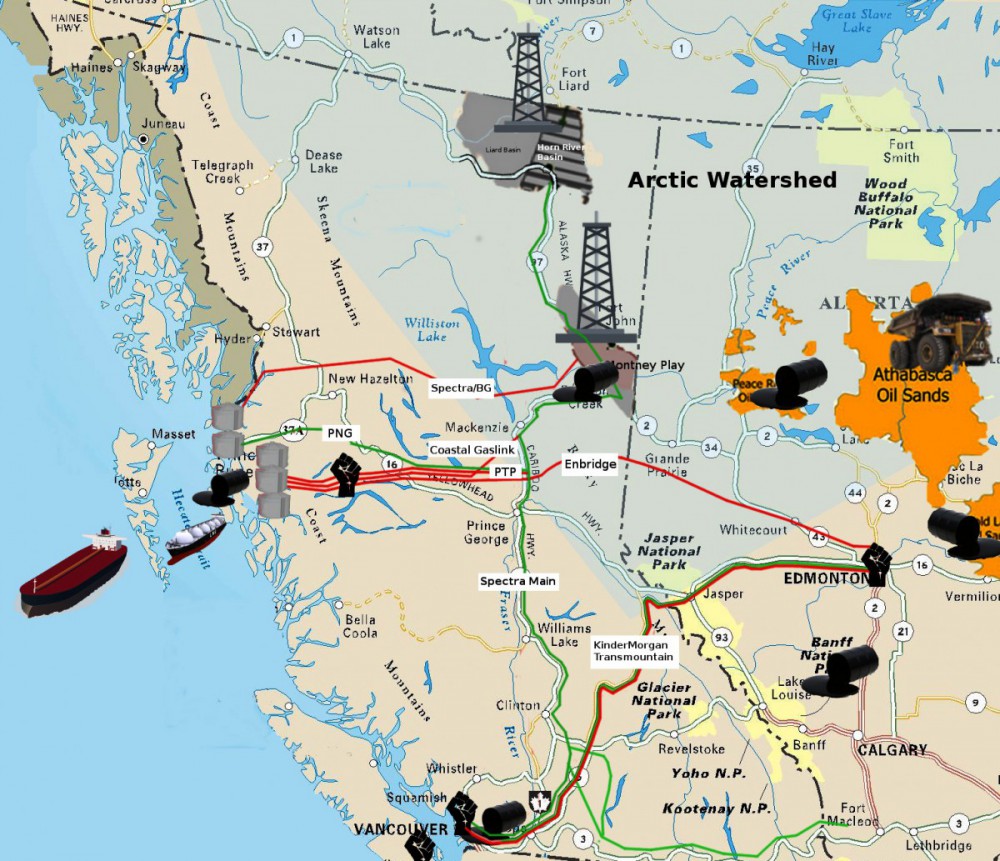

Since then, Chevron continues to work in the area, preying on the territories of neighbouring clans who have also not consented to any pipeline, but who have been unable to occupy their territory in order to protect it as the Unist’ot’en have. It is uncertain what the next move will be. The GoPro-style cameras worn by Chevron’s representatives at the bridge suggests the purpose of their visit may have been to collect video evidence for a possible injunction against the camp.

Undaunted by the encroaching threats, life at the Unist’ot’en Camp remains busier and more productive than ever. Work continues on Phase One of the Healing Centre, the root cellar is being renovated, the garden continues to grow, and berries are being harvested. Security is maintained by dedicated volunteers who are managing 24/7 shifts at the bridge as well as keeping a presence at several satellite camps throughout the territory. There is still time for celebration too, most recently on August 1, when the clan gathered for a feast to celebrate the current and two previous Knedebeas (Unist’ot’en head chief).

The grandmothers, mothers, nieces and daughters who form the core leadership of their matrilineal clan, remain resilient. They have made the choice to do what is necessary to protect the lands of their ancestors. They are not intimidated by the RCMP, Chevron, or the Canadian government. They know that they have never ceded or surrendered their land, and as plaintiffs in the Dalgamuuk Court case they paved the way for recent victories such as the Tsilhqotin Decison. This position is summarized in the Unist’ot’en Declaration, released August 6. If forced back into the colonial court systems, the Unist’ot’en’s could make a case for an area of land amounting to tens of thousands of square kilometres in the heart of so-called “British Columbia.”

Even so, the threat to Unist’ot’en Camp should not be downplayed or underestimated. By opposing pipelines, the Unist’ot’en are standing in the way of fossil fuel export development that is the core of the Canadian government’s industrial engine. It makes them a prime target for new legislation such as Bill C-51 and its vague clauses referencing “critical infrastructure.” As in generations past, the RCMP remain the enforcers of colonization. The RCMP officers who visited the bridge clearly revealed they do not respect the sovereignty of Unist’ot’en territory and alluded to the possibility of using the Motor Vehicle Act to force their way in if they desired to. Action against Unist’ot’en Camp could come directly from the RCMP and not even require Chevron to file for an injunction.

A call for support has been put out. Front-line able persons are encouraged to join the Unist’ot’en at their camp. Those who cannot physically be there can send material or financial support. Solidarity actions against Chevron and their investors are also welcomed. Disrupting business-as-usual at their offices is an opportunity to relay the message that Chevron’s proposed PTP pipeline does not have Unist’ot’en consent and should be abandoned. A victory against Chevron could spell doom for other proposed projects such as TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink and Enbridge’s Northern Gateway. It will show once again that alliances between Indigenous people and grassroots supporters are a powerful combination capable of stopping large-scale fossil fuel development.