On March 5, 2023, activists gathered inside the Metro Toronto Convention Centre holding banners rippling with messages: “WATER IS LIFE #Wet’suwet’enStrong,” “LIFE OVER PROFIT.” Entrances were obstructed by long rolls of blue cloth painted with fish. This action, orchestrated by Mining Injustice Solidarity Network (MISN), took place at the world’s largest annual mining event: the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) convention. From my computer in Kitchener, some 100 kilometres away, I read detailed accounts of the event. A joint press release by MISN and MiningWatch Canada reported that protest organizers were forcefully ejected by security. Even after being kicked out, protesters spilled onto the sidewalk, urging convention-goers and the public not to sacrifice our watersheds, lakes, and oceans for critical minerals and capital. The protest and MISN’s campaign made me think of Anna Badkhen’s writing about how our world is “tunneled and pierced by water yet at once held together by it.” On March 7, the last evening of the convention, faith-based groups held a vigil outside the centre for victims and resisters of mining, holding space for grief and prayers as prophetic disruption.

In her 2018 book A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, Kathryn Yusoff names Canada as one of the biggest extraterritorial mining countries in the world and the “largest national global mining corporation.” While it’s true that modern mining is multinational, Canada is still home to over half of the world’s mining companies and is implicated in over 75 per cent of all mining operations globally. These profiteers flock to Toronto, the belly of the beast, to attend PDAC’s annual convention and sidle up to industry players and government officials. Last year, Canada’s national resources minister Jonathan Wilkinson made an appearance to announce a $344 million investment toward “the development of a dynamic and competitive critical minerals sector,” a slice of the $3.8 billion the federal government has earmarked for future mining projects.

Between 2020 to 2023, approximately 2,375 people were reported as killed, injured, or missing due to mining-related incidents globally.

Four days after the PDAC convention concluded, eight miners in Tanzania’s Geita region drowned in an unsanctioned mine pit that was suddenly flooded with rainwater. In the middle of March, a coal mine explosion led to 21 fatalities in Sutatausa, Colombia, a region predominantly inhabited by Afro-Colombians and Indigenous labourers. And on March 30, in Sudan’s Northern state, heavy machinery use in a gold mine caused a tunnel collapse, killing 14 miners and injuring over 20. In the month of March 2023 alone, at least 55 people died and dozens more were injured as a result of their direct involvement in mining operations. These incidents speak to the death and destruction that always follow mining and mines, a fact glossed over at PDAC as an acceptable cost of doing business. The incidents also collectively highlight the disproportionate impact of mining: 95 per cent of the global mining incidents reported that month occurred in Afro-Black territories and communities.

***

In 2021, I wrote an investigation for The Breach exposing the influx of Canadian mining activity in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region while a bloody civil war raged. During that investigation, I found out that my cousin was working in a mine in Tigray and that my extended family had lost contact with her since the fighting started. Distressingly, Amnesty International had recently released a report on the forceful displacement and extensive mass rape happening during the Tigray war. To this day, I have no idea where my cousin is or if she’s even alive.

Learning about all the mining activity in Tigray brought into sharp relief how states and corporations see war as an opportunity to advance their own interests in land expropriation and resource extraction. For example, in Ethiopia, land is inherited through blood or kinship ties. Through rape, beatings, and murder, the Ethiopian government has seized land families have held for generations, and granted mining companies increased access to those lands.

Canada is home to over half of the world’s mining companies and is implicated in over 75 per cent of all mining operations globally.

Mining is inherently violent. Canada has a long history of extracting capitalist value from the Earth, breaking people and communities in the process; a brutal splitting of relations between land, humans, and non-human life forms. I’m drawn to stories of resistance against state violence and corporate exploitation, particularly resistance to mining and especially in the Horn of Africa. My parents, after all, were refugees who fled war in Ethiopia and Eritrea in the late 1980s. I was born in Canada, far removed from my parents’ experiences, but aware of the long shadows of war that have followed them. The gaps in my knowledge about my family and our histories drive me to write this article. It’s like what Saidiya Hartman writes about unknown histories: “The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them.” So, while this article will likely be read as a form of resistance to the exploitation and destruction of mining, for me it is also a yearning for stories, like that of my cousin who has disappeared in Tigray’s mines. This work is my way of connecting with my family’s past and contributing to the fight against mining and all resource extraction industries.

***

According to news stories listed on Wikipedia’s current events portal, between 2020 to 2023 there were approximately 2,375 people reported as either killed, injured, or missing due to mining-related incidents globally. This represents only a fragment of the broader picture, as many incidents go unreported or underreported, particularly in regions with limited media coverage. As most stories omitted details about the ethnicities of those killed or injured, I considered instead the impact of mining in Afro-Black communities, which I classified as countries in Africa, the Caribbean, and South American countries with high numbers of Afro-descendant populations (based on the stories included in the analysis, these countries were Brazil, Colombia, Suriname, and Venezuela). Over that four-year period, Afro-Black communities, accounting for 52.5 per cent (32 out of 61) of the total affected areas, experienced a disproportionately high frequency of mining incidents, compared to the combined 47.5 per cent (29 out of 61) in non-Afro-Black communities – Asia (18), Europe (6), North America (2), and South America (2). The number of dead, injured, and missing from these incidents barely scratches the surface of the total harm of mining, as the industry contributes significantly to a range of health issues and environmental pollution.

Modern mining forces debilitating migratory and labour patterns that overwhelmingly devastate Afro-Black and Indigenous communities.

All these harms stem from a modern extractive geography Martín Arboleda calls the “planetary mine,” which is dictated by systems of capital and global supply chains. Modern mining is characterized by transnational corporations and territorial infrastructures, advanced technologies that scan and bore the subsurface for mineral deposits, and automated machines that fragment the Earth around the clock and without needing to stop – and all of it, cumulatively, forcing debilitating migratory and labour patterns that overwhelmingly devastate Afro-Black and Indigenous communities.

One of Canada’s many roles in the creation of the planetary mine can be seen in the government’s investments to modernize other countries’ mining sectors; for instance, Canada helped build the Ethiopian National Mining Cadastre System (ENMCS), a digital platform made possible with funding from Global Affairs Canada through the Supporting the Ministry of Mines (SUMM) in Ethiopia Project. Launched officially in April 2016, one primary objective of SUMM was to establish an effective licensing system in Ethiopia. The ENMCS portal serves as an accessible online database of Ethiopia’s geological resources, a spatial technology streamlining the permit application process for foreign and domestic mining companies, including several Canadian firms.

My cursory review of the cadastre system revealed that, as of late 2023, over half of the mining licences in Tigray were for gold and base metals, with the value of these deposits estimated from hundreds of millions to billions in Canadian dollars. Many people have been drawn to Tigray’s mythical reserves of gold for hundreds of years. In fact, historians trace mining practices in Tigray back to at least the 17th century. Today, rural youth will wander Tigray’s lowlands like the Weri’i River valley to search for placer gold alongside industrial-scale operations, the majority of them Canadian-owned.

In 2020-2021, Canadian mining assets in Northern Africa and the Caribbean soared by 43.2 per cent and 9.5 per cent, respectively.

I asked Jamie Kneen, an Ottawa-based researcher with MiningWatch whom I had also interviewed for my 2021 investigation into Tigray, about the current state of Canadian mining activities in the Caribbean and other regions in Africa. Kneen was only aware of a handful of Canadian mining projects in Cuba and Jamaica, and what he referred to as “problematic installations in Suriname and Guyana, Maroon and Indigenous communities especially.” That’s not to say there are no Canadian mining interests on the islands; almost two months after our interview, C3 Metals, a Canadian mining firm, reported their discovery of copper and gold in Jamaica’s Provost area after investing millions and drilling holes hundreds of metres underground.

As Owen Schalk highlighted in an article for Canadian Dimension, Canada’s global mining investments have skyrocketed in recent decades. According to data from Natural Resources Canada, in 2022, all Canadian-owned mining operations were worth $273.4 billion, but an astounding 70 per cent ($188 billion) of that value were listed as foreign assets, $36.5 billion of which were in Africa. In 2020-2021, Canadian mining assets in Northern Africa and the Caribbean soared by 43.2 per cent and 9.5 per cent, respectively. Côte d’Ivoire’s assets almost tripled, with increases also prominent in Colombia (19.5 per cent) and Ghana (12.4 per cent), reflecting a strategic shift toward these Afro-Black communities.

***

Similar to my findings in my investigation on mining in Tigray, Kneen confirms Canadian mining companies’ mine development and production interests, whether the companies operate internationally or in Canada, “seems to be now in gold.” Whether in Burkina, Mali, Senegal, Mauritania, or Tigray, Kneen describes how mining companies looking for gold typically start by mapping areas where locals already mine gold, as many communities are only able to make a living from “combining agriculture and small-scale mining.”

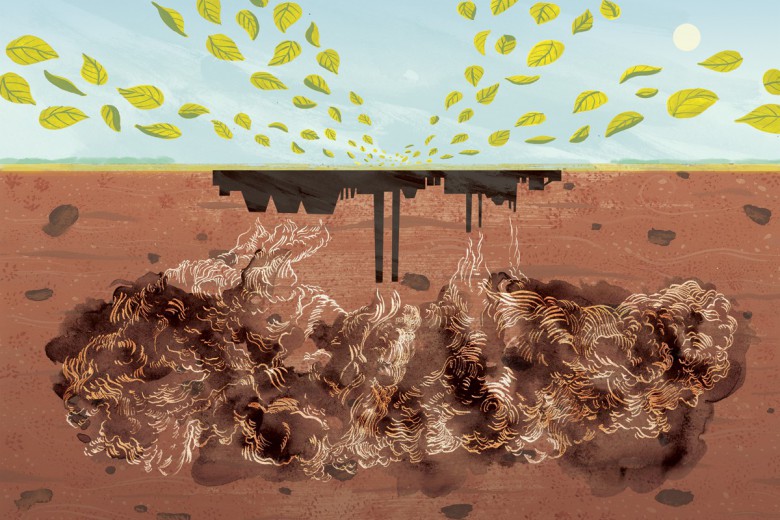

Mining companies remove water from these areas, continuously emptying out local reservoirs until “suddenly, there’s no water for anybody.”

These companies then swoop in with industrial mines that dig exactly where small-scale miners are working and living, effectively displacing them. To reach deposits below the water table, whether by shaft or open pit, mining companies have to remove water from these areas, continuously emptying out local reservoirs until “suddenly, there’s no water for anybody.”

A recent onslaught of news articles suggests a massive shift in mining focus is now occurring, an inorganic fever dream spurred on by the “green economy.” In December 2022, Canada launched its Critical Minerals Strategy, targeting 31 minerals key to the green and digital economy, including cobalt, gallium, lithium, and other rare earth minerals needed for technologies from EV batteries to defence systems. Despite this strategic shift toward “critical minerals,” Kneen states that in Afro-Black communities, he sees many more Canadian mining companies, especially junior firms, remaining focused on gold despite its limited utility for technologies or weapons manufacturing. This is largely because gold mining can offer companies massive returns on relatively small investments. In other words, Kneen states dryly, these mining firms pursue whatever minerals the market is interested in, and it’s purely profit seeking.

***

Despite the relentless hunger for gold on the part of most Canadian companies, Afro-Black communities in the Caribbean, South America, and Africa will continue to see more corporate and state actors look to Afro-Black homelands to satiate the global demand for critical minerals. This demand, driven not just by a surge in tech but also by capitalism’s response to ecological crises and climate activism, shifts focus to “green” technologies reliant on minerals like lithium, furthering extractivism and exploitation. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), for example, holds 60 to 70 per cent of the world’s coltan reserves, a highly sought after mineral in the high-tech industry, and roughly three-quarters of the world’s supply of cobalt, a crucial mineral used in renewable energy technologies like electric vehicle batteries. However, coltan and cobalt mining in the DRC is a brutal affair – there have been many documented reports of child labourers who face harassment, sexual abuse, and exposure to lung cancer–linked substances like radon.

The violent racialization of Blackness and the colonial logics of extraction transform Africans into “living minerals” marked for domination and exploitation.

At its essence, the Canadian mining sector is one monstrous, cyclical neo-colonial project. This approach dovetails with Canada’s broader strategy of backing the forced removal of Indigenous people from their land – even removals verging on war crimes in places like Ethiopia – under the rationale that fewer Indigenous voices equate to diminished resistance against its widespread extraction endeavours. But, of course, this isn’t exactly new. Canada was created with wealth accumulated through the transatlantic slave trade and mining regimes. Black bodies existed outside the category of human and were commodified like mined gold and ore. The violent racialization of Blackness and the colonial logics of extraction are mutually constitutive processes that, as Achille Mbembe describes, transformed Africans into “living minerals” marked for domination and exploitation.

***

Global mining activity has been met with fierce opposition. As recently as November 2023, mass mobilizations and protests against the largest open-pit copper project in Central America cost First Quantum Minerals, a Canadian mining company headquartered in Vancouver, over $6 billion, or 52 per cent of its value, in a matter of days. On November 28, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the 20-year contract granted to First Quantum was unconstitutional.

My original plan for this story was to locate and highlight Black folks in Canada who were also mounting similar or related forms of resistance to Canadian mining. I could find many examples of Indigenous communities in so-called Canada pushing back on mining projects. Especially encouraging were Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson who, in their book Rehearsals for Living, centred the harms of Canadian mining alongside their calls for Black and Indigenous “constellations of co-resistance.” I contacted the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project (JCAP), a legal clinic aiding communities affected by resource extraction, and KAIROS, an initiative uniting Canadian churches for ecological justice, to see if they could point me toward Black-led organizing in Canada strategically resisting mining.

Mass protests against the largest open-pit copper project in Central America cost Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals over $6 billion, or 52 per cent of its value, in a matter of days.

Both groups responded, but only JCAP was able to refer me to someone – Dr. Sara Ghebremusse, an assistant professor at Western University’s faculty of law who researches mining governance, law and development, and African legal studies and human rights. When we connected on Zoom in late October, I slipped into an easy familiarity with Ghebremusse; we are both Eritrean, both born in Canada. My first thought was that she looked like she could be family, like a distant relative. Responding to my queries from her office in London, Ontario, Ghebremusse explained that Black-led resistance to mining in Canada primarily takes the form of scholarship in academic spaces and legal actions against mining companies in Canadian courts. The most famous example of this legal resistance is a 2014 human rights lawsuit against Nevsun Resources Ltd. brought by three Eritrean refugees and former mine workers, Gize Yebeyo Araya, Kesete Tekle Fshazion, and Mihretab Yemane Tekle. Headquartered in Vancouver, Nevsun enslaved, tortured, and committed other abuses against its workers at its Eritrea mine. Nevsun ended up agreeing to pay the workers a confidential settlement.

“The same lawyers that took on that Nevsun case,” Ghebremusse tells me, “just last year filed a lawsuit against Barrick Gold, related to mining affairs in Tanzania.” Ghebremusse notes that this specific gold mine has been subject to litigation in the U.K., but this was the first time Barrick Gold has faced these kinds of accusations in Canadian courts. Ghebremusse also referred to some other legal battles against Canadian mining companies in Canadian courts, including a case in Quebec against Anvil Mining, a Montreal-based firm accused of using rebel forces in the DRC to incite more conflict as cover for mining companies’ expanded operations.

In Ghana, women are challenging China’s neo-colonial mining exploits by documenting corruption, disputing wage gaps, and refusing to sell land.

However, legal challenges are limited in what they can accomplish, particularly against companies operating in Africa. Ghebremusse explains that these cases often hinge on procedural grounds, meaning Canadian courts first determine whether they should hear cases involving harm in another jurisdiction, as in the Nevsun and Anvil cases. This includes dealing with defence strategies that challenge the court’s authority or the validity of the lawsuit, which is a frequent issue in international legal cases in Canada. This means that it is incredibly difficult to hold Canadian companies accountable for injustice, injury, and death faced by mine workers in countries such as Ethiopia. The Nevsun case ended in a rare settlement and, at the time of writing, the outcome of the Barrick lawsuit is still uncertain.

Beyond legal actions that reflect a kind of “functional resistance,” Ghebremusse says she’s yet to come across widespread examples of grassroots Black resistance to mining in Canada. “From the perspective of Black resistance in the diaspora, especially in Canada … I’ve not quite seen it.” Reflecting on her own Eritrean heritage, she comments on how even though the Nevsun litigation was a precedent-setting human rights win, she didn’t really see the legal victory taken up or celebrated within the Eritrean diaspora. And neither did I. We discussed how strange that is, considering that the Eritrean community in Canada is deeply invested in what happens back home, as we’ve both witnessed in our communities. This muted response, she suggests, might stem from the complexities of Eritrean politics and the resulting divides.

What role should the wider Black diaspora in Canada play in resisting mining? How do I ensure my own organizing is non-extractive?

There is, however, Black resistance to mining happening elsewhere. In South Africa, Black communities are actively opposing the expansion of a heavily industrialized mining sector that increasingly produces toxic waste and wastelands for gold and uranium, continuing a legacy of resistance to racial hierarchies of apartheid-era mining regimes. In Ghana, women have been challenging China’s neo-colonial mining exploits by documenting corruption, disputing wage gaps, and refusing to sell land. Many Ghanaian women also defy orders not to work in mines while menstruating, an outright refusal of patriarchal taboos that their blood might contaminate the gold. Jamaican Accompong Maroons, descendants of formerly enslaved Africans, are pursuing legal action against the Jamaican government for granting Canadian mining corporation Noranda a lease to expand their bauxite mine dangerously close to their ancestral territory of Cockpit Country. Nestled in Jamaica’s interior, Cockpit Country is a biodiverse region home to the island’s largest contiguous rainforest and roughly 40 per cent of Jamaica’s freshwater. Bauxite ore is what aluminum is made from, and decades of bauxite mining and aluminum refineries have resulted in lands that can no longer be farmed and contaminated water supplies elsewhere on the island.

There are a handful of African, Caribbean, and Black scholars in Canada who are willing and able to challenge the Canadian mining sector’s governance practices and operational negligence, but this pushback is fragmented and it is rarely spearheaded by Black individuals or groups. Canadian non-governmental organizations, like MiningWatch, are active in this space, but there’s a notable absence of Black-led advocacy. “That’s always something that I’ve been curious about,” Ghebremusse remarks, leaning back in her seat. “Where are Black people in the diaspora who care? I don’t know,” she says, looking at me intently through her screen. “I assume a lot of us care about what’s going on, but where are we in those spaces?” As our call comes to a close, Ghebremusse poses one last question: “does the Black diaspora protest differently, perhaps less visibly?” She ventures a possible answer: perhaps a sense of insecurity or desire for safety nudges us toward quieter, less public forms of resistance, like academic scholarship. We paused here, letting the question hang in the air for a beat, and then signed off.

***

Effective resistance to mining must be planetary and translocal while also grounded in specific places. It is increasingly evident that we carry a moral responsibility, as folks living inside the heart of this imperial nation, to address and confront Canadian mining violence. Perhaps we need different entry points into this work, such as Christina Sharpe’s “provocation and [...] invitation to think, imagine, be, and do differently in the spaces where we find ourselves.” Sharpe challenges assumptions that renewable energy is clean and harmless by pointing to the rare earth elements needed to produce it. Her thinking against renewal brings forth questions relevant for strategic mining resistance:

Who is doing that work of extracting the minerals? Who is risking their lives in order to try to live? Who is at risk of being trapped, dying, or being murdered? Whose lives are at risk for the renewables that are not available to them and the mining of which also means the polluting of water sources and the Earth, and the creation of cancer clusters and more? The languages of livability often produce more unlivability; the logics of renewal produce renewed devastation and ongoing exhaustion.

It’s easy to become overwhelmed when coming to terms with how the violence of Canadian mining is part of a much larger system, obscured by the sheer massiveness of these conglomerates of states and transnational corporations driving new forms of capitalism, neo-colonialism, and imperialism. I’m inspired by activists from Tigray Advocacy Canada who have attended rallies outside of PDAC to speak alongside Indigenous land defenders and others whose communities/lands have been impacted by Canadian mining. We can look to movements like the Palestinian call to boycott, divest from, and sanction (BDS) Israel until it complies with international law to ignite a similarly global stand against mining, centred on Black liberation. Much talk and money is turning to the influx of mining projects in Canada, like the Ring of Fire in Treaty 9 territory; the tone is hopeful, techno-optimist, and there’s a feeling of inevitability about the massive undertaking. However, we already know the collateral damages accrued by Canadian mining companies in the Global South, where they have displaced and destroyed Afro-Black communities with al-most total impunity, operating at a dizzying pace with devastating ecological and social impacts.

I yearn for Black folks in Canada to think together about our futurities in the face of multiple, unfolding catastrophes; we need projects designed for the Anthropocene, anchored in an imagination and ethic that is capable of bridging us to the afterlives of mining.

At an MISN orientation last October, something one of the organizers said about their principles resonated with me: the extractivism they seek to dismantle must not be replicated in their modes of relation and organizing. This careful, intentional approach is vital. Returning to reflect on my conversation with Ghebremusse, I find myself asking a series of questions: what role should the wider Black diaspora in Canada play in resisting mining? How do I ensure my own organizing is non-extractive? I ponder these questions, haunted by all the topographies – people’s specific homeplaces – that may be razed, gutted, torn asunder in the coming decades under global “green economy” pressures. I sit with the desire for more people to be critical of Canadian mining. But perhaps even stronger than that is my yearning for Black folks in Canada to think together about our futurities in the face of multiple, unfolding catastrophes; we need projects designed for the Anthropocene, anchored in an imagination and ethic that is capable of bridging us to the afterlives of mining.

*Sincere gratitude to Damian Mikhail and Craig Sloss for their excellent analysis of what limited data exists on the Canadian government’s mining investments.

**Correction, April 5, 2024: This article has been corrected to specify that coltan mining is linked to high-technology, whereas cobalt is a critical mineral used in "green" technologies.