The Ring of Fire is the name given to a region of northern Ontario by Noront Resources founder and former president Richard Nemis. It’s reported that he was a fan of Johnny Cash, the famous “Man in Black” whose tune is considered one of the greatest country songs of all time by the likes of Rolling Stone. In it, Cash falls into a fiery ring over and over again. It’s an ear worm, but it’s also a symptom of insanity.

Nemis’s Ring of Fire isn’t really a ring at all, but a crescent-shaped blip on a map in the James Bay lowlands of northern Ontario. It is an area marked by coniferous forests and coated with peatlands. Waters spill from bogs into streams, rivers, and lakes before meandering into James Bay. Under the surface is some $60–$120 billion worth of copper, nickel, and chromite, among other desirable materials. For the Anishinaabayg, these materials are simply known as money rock.

The stakeholders, like Cash, are “bound by wild desire.”

The Ring of Fire has become a neologism for a not-yet-realized but unprecedented proposal to mine the land and transform First Nations communities. In exchange, government and corporate interests have promised that the project – and the billions of dollars of private investment they hope it will attract – will help free the Anishinaabayg in the region’s far north from their isolation and poverty for the next 100 years. The stakeholders, like Cash, are “bound by wild desire.”

Sacred responsibility

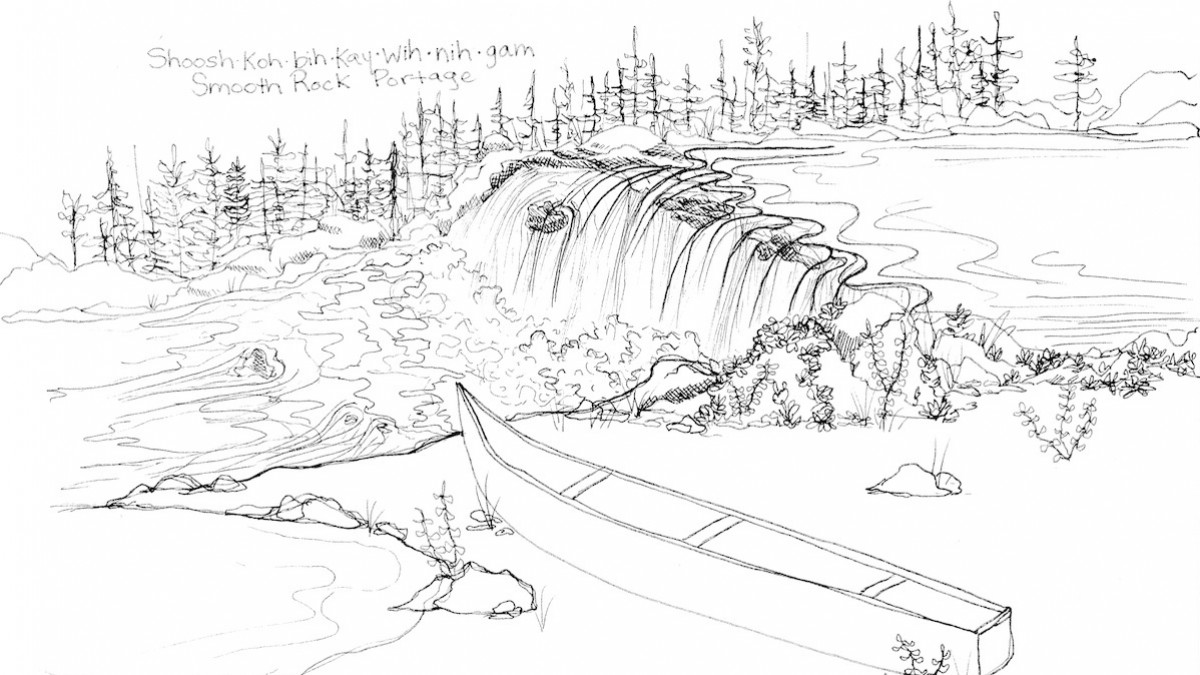

Existing literature on the Ring of Fire is plagued by missing or overlooked information. Let’s begin with the language of the Ojibway, one of the Anishinaabayg Peoples of the region. The immemorial history of the Ojibway People, their Pah-git-tin-nih-gay-win-nun (Laws) – the Laws of Creation, the Laws of the Land, the Laws of the People – and their shared knowledge of science, governance, economics, justice, and medicine, are encoded in the language itself. There is little mention of Anishinaabay epistemology in the literature on the Ring of Fire because it is overlooked, deemed worthless, or, as the history of residential schools shows us, the language was liquidated from the people by force.

Indigenous languages can establish legal precedent for stewardship of the land, since the rules of law embedded within the language precede the colonial laws of the Canadian government. At one time, treaties were signed by Ojibway ancestors using pipe and tobacco, not the English or French language, and the legal documents of Indigenous Peoples were authenticated by two-row Wampum Belts. To some this may seem peculiar, but it was equally alien for Indigenous people to use paper and pen. When signing documents with government representatives, the Ojibway language Anishinaabaymowin was used, together with spiritual ceremonies, to prepare agreements that Indigenous people still regard as sacred. Those agreements – among them, historical treaties like Treaty 9, which covers the Ring of Fire – have been ignored and broken repeatedly by Canadian governments. Their atrophy represents both a breach of Canadian law and a fissure of spiritual protocols.

Indigenous languages can establish legal precedent for stewardship of the land, since the rules of law embedded within the language precede the colonial laws of the Canadian government.

The Anishinaabayg are a spiritual people. In Anishinaabay prayer and thought, a-say-ma (tobacco) is used to offer mee-gwaych (thanks) for the aki (land) and nih-bih (water), for it harbours the stuff of life. The land is spoken to in ceremonies, and it is referred to as a being who lives and breathes. In their prayers, the Anishinaabayg made promises to protect the land and water for all time. These days it seems the Anishinaabayg need a lot of tobacco.

Original languages also elucidate why there exists a need to protect the land, water, and air for the good of the whole – for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. The Anishinaabay language cannot remove itself from spiritual discourse, for it is universally accepted that everything has a spiritual connection. Take, for instance, the etymology of the Anishinaabaymowin for “my little sister”: the word, nih-shee-mayns, is closely related to nih-bih (water) – so much so that they are nearly synonymous with each other. For the Anishinaabayg, water is family and family members are water. This is precisely the reason why most Anishinaabayg who speak the original language fluently do not venture to sell water as a commodity – to do so would be like selling our little sister.

The collective safeguarding of natural resources in northern Ontario for the coming Seven Generations is an ancient responsibility, a sacred and moral responsibility. Yet Marten Falls First Nation near James Bay, ground zero for the Ring of Fire, has been on a boil-water advisory for over 15 years. The water is unsafe to drink, the water treatment facility is defective, and bottled water must be flown in by the tonne. In some ways, oaths to ancestors have already been broken.

Far North sovereignty

Government officials, corporate representatives, and intermediaries regularly invoke the 2010 Far North Act to navigate how to mine the Ring of Fire. The act introduced a set of regulations for land use planning in the far north of Ontario – its stated aim was to protect 50 per cent of the boreal landscape while centrally involving First Nations communities in decision-making and revenue sharing. But in a brief for the Yellowhead Institute, environmental justice scholar Dayna Scott writes that the act was a colonial response to crisis: after members from Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation were convicted of contempt of court “for protecting their homelands from platinum mining as required under their own Indigenous laws,” the Court of Appeal for Ontario found their sentences excessive and released them from prison, and the province had to spend millions of dollars buying out two mining companies’ claims in the territory. Two years later, after rushed consultations, the Far North Act was introduced over the objections of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation. While Indigenous communities were allowed to map their lands and designate areas as open or closed to development, the act still gave the provincial government “ultimate and unilateral authority to approve mining developments, or roads and other infrastructure, even if those decisions run contrary to community land use plans whenever the ‘social and economic interests of Ontario’ are engaged,” Scott writes.

When Indigenous laws are degraded by Canadian law, so too is the language in which these laws are embedded. The Anishinaabay language was not implemented in the formation of the Far North Act, which means that the act is utterly irrelevant in Treaty 9 territory. The Far North Act is a mechanism for supressing Indigenous stewardship over the land. In this, the act is little more than the 1876 Indian Act masquerading under a different name.

The “weaponization of the health crisis,” Eabametoong First Nation member Riley Yesno tells CBC, “is a way to get their desired projects put through.”

Doug Ford’s provincial government first attempted to repeal the Far North Act in 2019 and is now dedicated to revising it, citing a desire to streamline economic development and remove red tape. The comment period for the proposed revision closed on January 14, 2021 – at the height of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This may not be a coincidence. Indigenous people living on reserve are 40 per cent more likely to be infected by COVID-19 than the rest of the population in Canada. It’s yet another disproportionate crisis that First Nations communities must manage. The “weaponization of the health crisis,” Eabametoong First Nation member Riley Yesno tells CBC, “is a way to get their desired projects put through.”

The Matawa Chiefs Council, which oversees nine First Nations communities in northern Ontario, also rejects the imposed deadline. As Eabametoong Chief Harvey Yesno stated in a press release, “Ontario has been unashamed in its aggressive approach to prepare to access the wealth and resources of the James Bay Treaty No. 9 territory,” adding, “our rights are of a higher priority than the interests of government, general stakeholders and industry investors.”

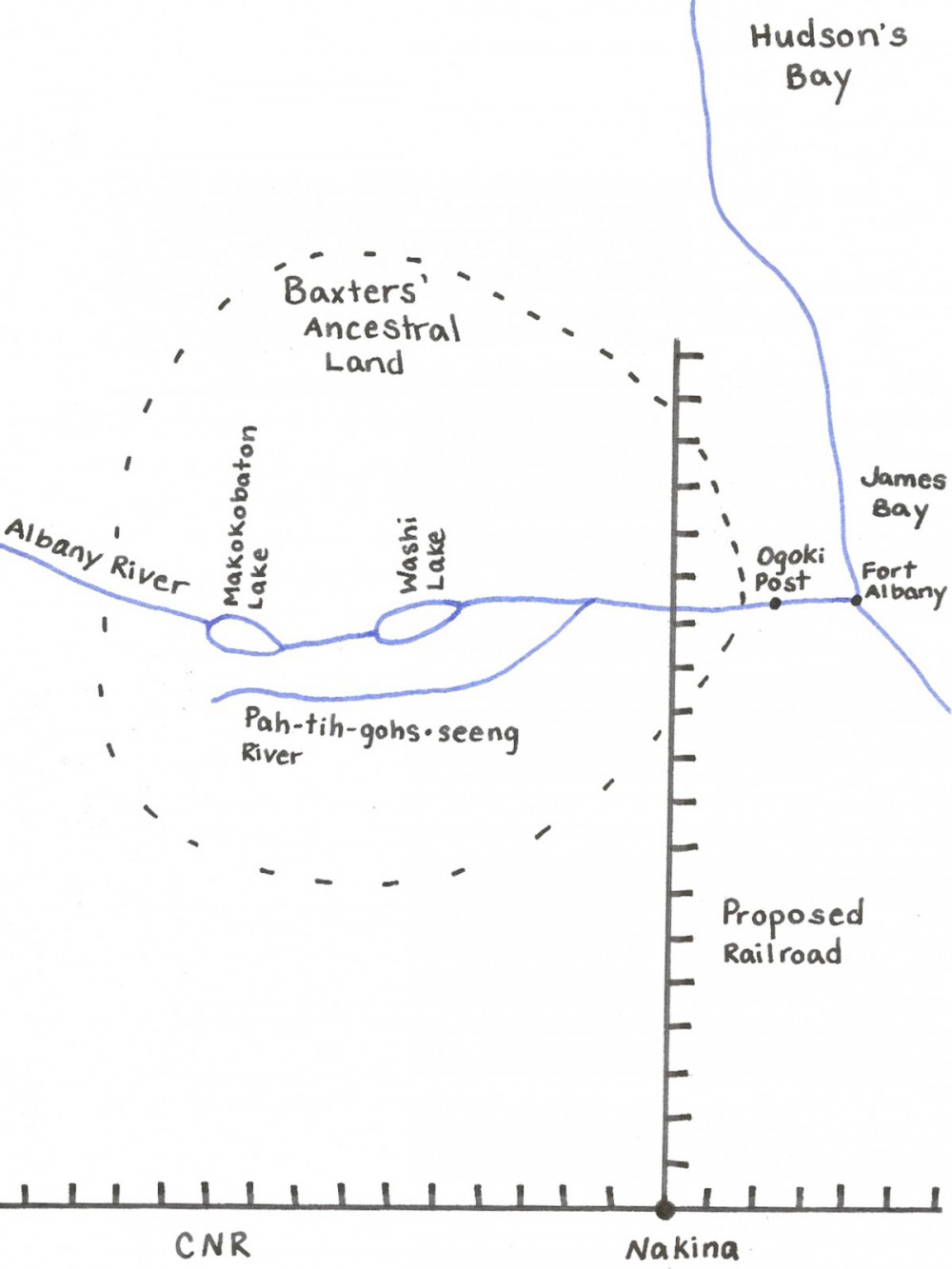

In spite of this, on February 7, 2021, the Sudbury Star reported that Canada Chrome Corporation is moving ahead with plans to construct 330 kilometres of rail from Nakina to the Ring of Fire, to be used for transporting ore south. Canada Chrome is a subsidiary of Toronto-based KWG Resources, which holds a partnership stake with China Railway First Survey & Design Institute Group (FSDI), headquartered in Xi’an, China. China consumes approximately 60 per cent of the world’s chromite, giving it a sizable interest in the political affairs of northern Ontario. Within the last few years, China’s publication of a new Arctic policy, proclamation of itself as a “near-Arctic state,” construction of a drift-ice camp in the Arctic Ocean, and bid to purchase a gold mine near the Northwest Passage are enough to raise questions over the Far North’s sovereignty.

For Seven Generations

It is worth paying attention to how resource extraction corporations and their proponents talk about the Ring of Fire. Stan Sudol is a freelance mining consultant who, in an op-ed for the Sudbury Star, writes that Canada’s “mining sector follows one of the highest environmental standards in the world and many of the metals that have been found in the vast region of relatively low biodiversity are essential for the green transition.” These talking points are widely parroted but largely false. Marten Falls First Nation rests on the second-largest peatland on Earth and is inside a great swath of Canada’s permafrost. Reports estimate that these soft lands sequester 35 billion tonnes of carbon – equivalent to the yearly emissions of seven billion cars. There is a good reason why Indigenous Elders call these the “breathing lands.”

What will the Far North look like in 2121? This does not seem like the “green transition” Sudol writes of, but instead a grey future.

Mining activities and their accompanying infrastructure, like the railway that Canada Chrome intends to traverse the Albany and Attawapiskat rivers, will unsettle areas of floating peat called muskeg. This will release carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change. A 2010 report by the Far North Science Advisory Panel warns that by “2050 […] it is projected that average temperatures and precipitation in the Far North will have increased enough to alter plant communities, degrade permafrost, lower water levels in lakes, rivers and wetlands, reduce ice cover on land and sea, and affect fish, wildlife and forests.” What will the Far North look like in 2121? This does not seem like the “green transition” Sudol writes of, but instead a grey future.

For a case study, we need only look to the De Beers Canada’s Victor diamond mine and its relations with the nearby Attawapiskat First Nation. De Beers is accused of failing to report mercury and methylmercury levels at its water monitoring stations; it pressured regulators for a third landfill site atop wetlands and paid a meagre $226 in royalties in 2014. The government likewise failed to train and support First Nations workers, and a promised college program to train local diamond-cutters never materialized. In 2016, while the mine was still in operation, a state of emergency was declared after 11 individuals from Attawapiskat attempted suicide in one night. Three years later, and two months after the mine closed, a second state of emergency was declared after tap water was found to be toxic. The outlook for the Victor diamond mine was once pretty – Mining Magazine voted it “mine of the year” in 2009.

In their prayers, the Anishinaabayg made promises to protect the land and water for all time. These days it seems the Anishinaabayg need a lot of tobacco.

In just a few generations, the Anishinaabay hunting and gathering society experienced a transformation – from living off the good of the land to negotiating huge land settlements with powerful mining corporations and occupying powers. At one point, there was hope that all First Nation communities would achieve economic prosperity, that companies and governments would make good on their promises of employment, health care, electricity, clean water, cheaper food, strong infrastructure, and safe homes. But promises made by thieves are not to be trusted. Angus Baxter, a Matawa community member, told mining company representatives after a general meeting that they will likely get their mines but the Anishinaabayg will get the shaft. Tay-bway! (He might be right!) Many years ago, a Choomis (Grandfather) dreamed that his traditional lands near James Bay were barren, devoid of all life. Anishinaabay people believe their Elders.

Ultimately, industrial resource extraction is unsustainable for the Anishinaabayg. There needs to be a different model – one that safeguards the land, water, and air; one that puts people first.

And the name is false. Naa-bin-gee-pih-zohn Ish-koh-tay is the Ojibway term for the Ring of Fire.