“water has a syntax / i am still learning / a middle voice”

—Rita Wong, “Pacific Flow”

“Do you speak Chinese?” an elderly Chinese couple asked me as I stood at the edge of a blockade at Clark and Hastings in Vancouver. It was the second day of solidarity actions with the Wet’suwet’en after the RCMP invaded the Gidimt’en checkpoint near the Unist’ot’en Camp on February 6. The sun had come out after a day of rain.

Oh shoot, I thought. How do you say “north” in Mandarin again? Okay, Beijing is to the north, so “bei” means north, and if I point up … uh, uh…

I had half a second to collect my thoughts: “So the cops went into – First Nations’ lands up north … the government – is stealing – Indigenous lands – and stealing their children … so we’re here, saying that’s not okay…”

In that moment, I didn’t have the vocabulary to explain that we were shutting down Canada in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en people’s peaceful defence of their homelands – against Coastal GasLink’s unlawful pipeline construction, against RCMP invasion, and against Canada’s colonial violence. I had no words – in any language, really – to convey the grief and loss that Indigenous communities face because of man camps full of pipeline workers and the violence they inflict upon Indigenous women and Two-Spirited people; the destruction of habitat of other-than-human relatives; and the razing of medicine patches, trapping grounds, and sacred sites.

In that moment, I didn’t have the vocabulary to explain that we were shutting down Canada in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en people’s peaceful defence of their homelands.

And yet the couple understood, nodding. I pretended to understand what they said back to me. After they walked away, I went back to being part of the blockade.

Making conversation with Chinese-speaking strangers, especially seniors, is a common experience for me. Despite not being able to read a Chinese menu or memorize routes of city buses, my ability to speak Mandarin and my youthful gait will often wash me to the shores of these elders’ lives. It’s not quite so common, though, that this shoreline would wind its way into the crowded throngs of civil disobedience, as I help stop traffic at the Port of Vancouver.

Later that night, I created a Google Doc: “How to explain what’s happening to the Wet’suwet’en people in Chinese.” My intention was to help other heritage speakers – and me – expand our vocabulary in order to explain current events to our Chinese-speaking family members, relatives, and neighbours. I asked people I knew on Twitter and locally if they could translate words like “hereditary chiefs,” “RCMP,” and “Indigenous sovereignty,” as well as slogans like “Consultation is not consent,” “Respect Indigenous law,” and “Reconciliation is dead.”

What has always been a source of grief – my lack of fluency and connection to family and culture – became my motivation.

Pockets filled with beach pebbles are all I’ve got for language as a 1.5th-generation Chinese settler and heritage Mandarin speaker. Creating this document was my way of asking my diasporic community to offer their skills and ingenuity in a moment when our participation is crucial. What has always been a source of grief – my lack of fluency and connection to family and culture – became my motivation.

I wrote “Respect Indigenous law” in Chinese on a sign and arrived at the blockade the next day.

A history of migrant-Indigenous solidarity

When Wet’suwet’en solidarity actions stopped traffic and blocked railway lines in February, OMNI Television was the only Chinese-language network covering blockades across the country. They aired a Cantonese interview with Bill Chu, founder of the Canadians for Reconciliation Society. Chu is one of several Chinese settlers unearthing the relationships between Indigenous peoples and the 15,000 Chinese migrants who built the railway that helped cement the fledgling Canadian state.

During the 1880s in the interior of what we would come to call British Columbia, Indigenous people and Chinese workers sometimes teamed up against the violence and discrimination they faced from white workers and foremen. The Nlaka’pamux recall stories of reciprocal care – like the times when Indigenous people nursed railway workers, who were left to die along the tracks, back to health. Remnants of Nlaka’pamux pit houses can still be found intermingled with abandoned Chinese residences, some of which mimic the Nlaka’pamux’s traditional pit houses. The Sto:lo also remember the Chinese railway workers who died of the flu at Sxwóxwiymelh and the miners who died of a blasting incident at Lexwpopeleqwith’aim.

Today, I see similar echoes of the Hong Kong protests of summer 2019 in the 2020 Wet’suwet’en rail blockades.

One haunting detail of Chu’s research is the parallel that he draws between the Tiananmen Square Massacre of 1989 – when hundreds of protesters were massacred by the Chinese military – and the so-called “Oka Crisis,” the fight to protect a Kanien’kéhaka burial ground from being desecrated by a golf course in 1990. Today, I see similar echoes of the Hong Kong protests of summer 2019 in the 2020 Wet’suwet’en rail blockades. Telegram, an encrypted chat app used to organize protests in Hong Kong, became a key source of updates during the weeks-long Indigenous youth-led occupation of the B.C. legislature steps.

In these moments of mass mobilization, we have opportunities to share strategies and wisdom between our communities. But such sharing cannot happen without translation, which helps us build reciprocal relationships while exposing similar experiences of state violence.

Translating the grassroots

Grassroots translation work has a history longer than my own short involvement.

When Strathcona’s immigrant enclave was partially bulldozed in the 1960s to prepare for the city’s attempt at building a freeway through Vancouver’s Chinatown, Shirley Chan translated for her mother, Mary Lee Chan, who organized the first protests against the freeway.

Similar intergenerational translations would prove pivotal in the public hearings about 105 Keefer Street in 2017, when residents of Vancouver’s Chinatown fought against a rezoning that would allow a developer to build three additional storeys of penthouse condominiums. During the hearings, low-income Chinese seniors’ speeches were cut in half because the city bylaws failed to account for translators in their speaking times.

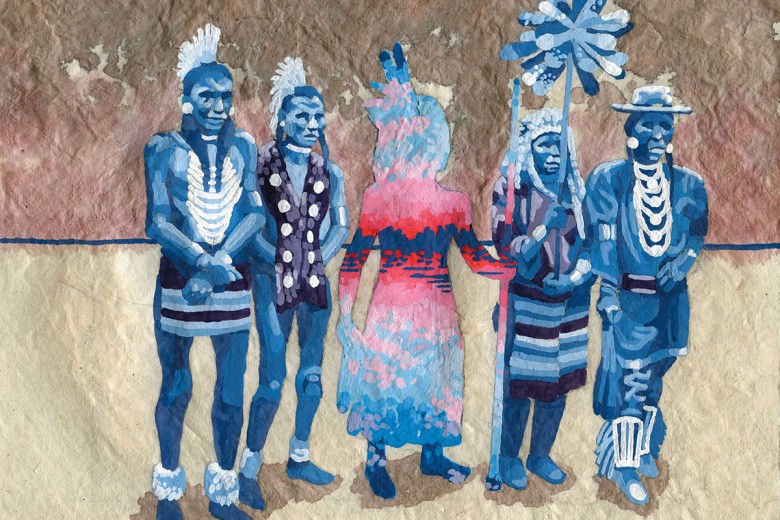

In 2014, leading up to raising the Survivors Totem Pole in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside in 2016 – a symbol honouring survivors of colonialism, poverty, and racism – I attended a First Nations and Chinese seniors’ meet and greet. There, elders who rarely interact because of language barriers but who have long lived alongside one another exchanged stories for the first time. Hearing each line of their stories repeated in English, Cantonese, and Mandarin made me realize just how powerful translation can be for bringing communities together.

In 2016, during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, people began translating statements about racial justice, police violence, and anti-Blackness into their mother tongues – Arabic, Bengali, Farsi, Tagalog.

Last summer, Lausan – an online leftist publication responding to the Hong Kong protests – translated stories of Hong Kong’s Southeast Asian migrant workers from English into Indonesian, and translated sex workers’ stories from Traditional Chinese into English. In 2007, grassroots migrant justice group No One Is Illegal translated a Nisga’a Elder’s welcome speech to a Punjabi refugee from English into Punjabi. In 2016, during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, people began translating statements about racial justice, police violence, and anti-Blackness into their mother tongues – Arabic, Bengali, Farsi, Tagalog – and so “Letters for Black Lives” began.

This year, Asians in Support of Wet’suwet’en – a group formed shortly after I created my document – wrote a statement of support for the Wet’suwet’en people, and translated it into 15 languages.

One week after the blockade at Clark and Hastings, organizers Kimberley Wong and Rachel Cheang hosted an intergenerational banner-making party in Vancouver’s Chinatown. There, several seniors I had met through my work on a Chinese seniors’ art and storytelling project busied themselves painting the characters for “Respect Indigenous sovereignty” and “Shame on the RCMP” in Traditional Chinese. Around them, others created colourful signs in Burmese, Asi, Tagalog, Spanish, Vietnamese, and Korean.

When several of us arrived at the Renfrew rail blockade later that night, the small blockade stirred and shifted towards us. We shared with the women and Elders of the gathering what we had written on our banners and signs. I thought of the Chinese ancestors who built both the railway that displaced Indigenous people, and early relationships of solidarity with them. When the Vancouver police served an injunction a few minutes after we arrived, I wondered if our show of support for the Wet’suwet’en land defenders posed a threat to Canada, just like Chinese migrant workers’ relationships with Indigenous people did many generations ago.

Who we bring along

Though racialized settlers benefit from – and thus are complicit in – Indigenous peoples’ dispossession, February showed us that there is a clear path to transforming our roles here on stolen lands.

In “Being with the land, protects the land,” Leanne Betasamosake Simpson observes that “[t]he practices of life-giving land protection of the Wet’suwet’en reminds me that blockades are like beaver dams. One can stand beside the pile of sticks blocking the flow of the river, and complain about inconveniences, or one can sit beside the pond and witness the beavers’ life-giving brilliance – deep pools that don’t freeze for their fish relatives, making wetlands full of moose, deer and elk food and cooling spots, places to hide calves and muck to keep the flies away, open spaces in the canopy so sunlight increases creating warm and shallow aquatic habitat around the edges of the pond for amphibians and insects, plunge pools on the downstream side of dams for juvenile fish, gravel for spawning, home and food for birds. Blockades are both a negation [of] destruction and an affirmation of life.”

In those deep pools and wetlands, Indigenous land defenders generously created the conditions for im/migrant solidarity to thrive – the conditions for the revolution to be translated.

When the Vancouver police served an injunction a few minutes after we arrived, I wondered if our show of support for the Wet’suwet’en land defenders posed a threat to Canada, just like Chinese migrant workers’ relationships with Indigenous people did many generations ago.

While at the blockades, I poured hot chocolate for little ones; ate an oven-hot sweet potato; and witnessed Indigenous reclamation of land, language, song, and ceremony. I felt welcome where I often do not in mainstream activist spaces. This warmth and intergenerational care was in sharp contrast to the violence of the police, who would bar media and witnesses from filming arrests as they unfolded; forbid lawyers from speaking with arrested Indigenous youth; and separate those arrested into different paddy wagons despite hours of negotiation. Days after, I felt sick remembering their uniforms and guns.

If that sickness is a sliver of what Indigenous people feel, dispossessed from their lands and criminalized for defending them, then the warmth and hope of the blockade is a glimmer of the future that Indigenous people are fighting for.

When Wet’suwet’en language speakers translate their stories, law, and system of governance into English for the settler world to understand, they generously share themselves in the same breath as they experience Canada’s colonial violence and erasure.

The larger the audience, and the louder our dissent to the Canadian state’s theft and violence, the more likely it is that the state will back down. When we bring our ancestors, elders, aunties, and young ones along, there’s a fighting chance that we will win.

Until the RCMP and Coastal GasLink leave Wet’suwe’ten lands, and until Indigenous sovereignty is fully respected, let there be flyers all over the streets of Chinatown, mailboxes filled with zines about Wet’suwet’en, and Telegram dinging continuously. Let these messages be waves.