In March 2017, El Salvador banned all metal mining. At that time, 90 per cent of the country’s water was undrinkable, and it was the second most environmentally degraded country in the Americas. The historically unprecedented victory was the result of a decades-long struggle against Canadian mining company Pacific Rim. Supported by 240 civil society organizations from around the world, impacted communities gave accounts of their experiences with Pacific Rim’s parent company and exposed the unsavoury truths behind the company’s promises of “responsible mining.” After blockades, international delegations, and relentless organizing, the company’s credibility was undermined, and legislators across the political spectrum voted in favour of the ban.

This is one of many stories of collective action against the mining industry that Joan Kuyek, a long-time community organizer and anti-mining advocate, uses in her most recent book. Kuyek calls Unearthing Justice “a personal story, in which I want to share what I have learned through decades of experience working to limit the damage caused by the mining industry in Canada.”

Kuyek has been a political activist since her involvement with the New Left in the 1960s, and she has spent her career working with mining-impacted communities in various capacities, including as the co-founder of MiningWatch Canada. Unearthing Justice has been in the making since 2011, when Kuyek published Community Organizing, a guide to Canadian activism that lays out paths and tactics for grassroots mobilization.

Her newest book is divided into five sections. Each tackles different angles of the mining industry, illustrates them through narratives from mining-impacted communities, and dissects them to shed light on a deliberately obscure industry. The first section is an introduction to the science and geology of mining; the second describes the social and environmental impacts of the industry; the third outlines the economic structure of the industry; the fourth discusses mining regulations and their enforcement; and the fifth, the most substantial, lays out different methods of resistance. A cover-to-cover read will help the reader develop a well-rounded knowledge of an opaque industry, but it may be most useful as a reference book, kept by the desk to help clarify industry jargon as it arises.

This book is not, nor could it have been, an exhaustive or encyclopedic text of everything there is to know about mining. Readers will learn how to interpret some of the information that can be found in corporate documents, but they will only find a few pages about how to gain access to the documents in the first place – a lengthy and bureaucratic process that journalists and lawyers spend years trying to master. Nonetheless, it leaves few stones unturned. The attentive reader will learn about the various toxic materials created by mining and the union-busting tactics used by mining companies. Perhaps most importantly, the book explains Canadian financial markets so that even a lay reader with no business background can begin to unravel the expansive and labyrinthine web of investors, shareholders, and different levels of governance that make mining companies so powerful in the first place.

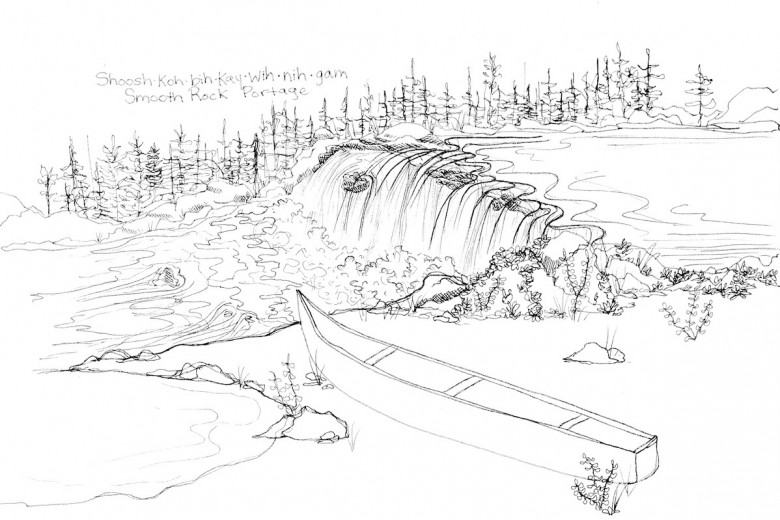

The bulk of the book focuses on mining and its opposition in Canada, which is where Kuyek’s expertise lies. The reader will learn, yes, about the struggle in El Salvador but also about the Robinson-Huron treaty, which the Anishnaabe were coerced into signing in 1850. The treaty allowed settlers to stake mining claims, a process that involved “discovering” ore and concretizing exclusive access to it, usually for a small fee. Yet there was documentation that the Anishnaabe had known about and been using the ore for a very long time, and they had even discussed it with the lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada 15 years before the treaty was signed.

Kuyek herself is a settler. However, her community-focused approach to both writing and organizing foregrounds the experiences of Indigenous people, highlighting their actions and organizing successes. In chapter 4, titled “Mining and Colonialism on Turtle Island,” Kuyek outlines different approaches that Indigenous peoples have taken toward mining, reconciling opposition to environmental exploitation with the fact that Indigenous people often have no choice but to work with mining companies in some capacity. Writing about the early days of MiningWatch, Kuyek stresses the importance of environmental activists (who are often settlers) taking leadership from (often Indigenous) mining-impacted communities. One option that she lays out for people who aren’t on the front lines is to help wade through the endless bureaucracy designed to prevent activists from accessing the information necessary to get mines shut down in different courts. The Canadian Network on Corporate Accountability (CNCA), for instance, is a coalition of civil society organizations that researches corporate wrongdoing and fosters public awareness of it. Groups like these help fight the mining lobby and, like with Pacific Rim in El Salvador, delegitimize companies.

The book also raises the big questions about the philosophy of mining, which Kuyek calls “the ultimate expression of the violence of colonialism.” She spotlights the idea of environmental economics, an alternative to Canada’s traditional understanding of economics, which asks: do we really need more gold and diamonds? Could we recycle them instead, or use different gems? Are the social and environmental costs of mining really worth the ore that we’re extracting? These arguments, put together in collaboration with mining-impacted communities and anti-mining advocacy organizations like MiningWatch, have been successfully brought to court multiple times in British Columbia to shut down various mining projects.

In covering the topic so thoroughly and from many different perspectives, Kuyek masterfully takes apart an all-powerful, larger-than-life industry to highlight the different paths to solidarity and resistance that people living in Canada may take. Unearthing Justice is a textbook, a manifesto, and a labour of love all in one, a volume everyone who is interested in anti-extractivism should keep within arm’s reach.