This article was created as part of a package of writing to accompany Human Capital, an exhibit at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina. View the full package here.

In December 2016, as Donald Trump’s inauguration loomed, migrants living in the U.S. began to flee for their lives on foot. With their infants in their arms they trudged through the waist-deep snow at Roxham Road, a country road turned unofficial border crossing between New York and Quebec. Organizations like Black Lives Matter and Solidarity Across Borders worked double time, sending legal teams, providing food and warm clothing, preventing police brutality, and talking to the media. Canadian headlines were vicious. Words like “line jumpers” and “illegals” were used regularly on the news.

Where are those migrants now? Today, thousands of migrants work in long-term care homes in Quebec, helping to fill the high demand for workers there. But underfunding and privatization in long-term care homes have led to some of the most devastating outbreaks of COVID-19 in the country, accounting for 64 per cent of all COVID deaths in Quebec.

In the first six months of the pandemic, hundreds of Quebec's nurses quit their jobs. When Quebec Premier Francois Legault begged for people to sign up to become "guardian angels" – his term for health care and long-term care home workers – Ze Benedicte Carole, an asylum seeker from Cameroon, began volunteering in a long-term care home. In May, when she contracted COVID from residents at her work, she was told by a provincial health-care worker that she couldn’t get a test because she didn't have a medicare card. "When we die at the front lines, we're called guardian angels," she told the National Observer. "But when we need to be treated on equal footing, we're not guardian angels. We're nobody, we're invisible."

Instead of arming these workers with what they need – permanent residency, fair wages, and labour regulations – we have been clapping for them from our balconies at a scheduled hour, as they march to their deaths.

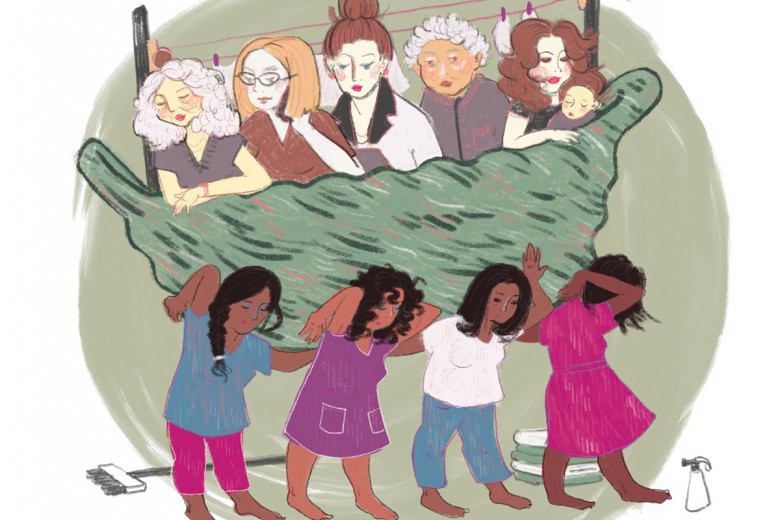

The past year of the pandemic has shown us what kind of work is truly essential to our collective survival: that which is done by nurses, cleaners, produce pickers, grocery store clerks, childcare providers, and teachers. All of this work provides what everyone deserves: food, shelter, education, safety, and health care. But this work is underpaid and undervalued, and as a result many Canadians don’t want to do it. In Canada, as in many wealthy countries, this critical work is disproportionately done by migrant workers, admitted into the country on temporary permits or staying without documentation at all. And instead of arming these workers with what they need – permanent residency, fair wages, and labour regulations – we have been clapping for them from our balconies at a scheduled hour, as they march to their deaths.

It's not a sustainable situation; it never has been. In the coming years, pandemics are predicted to become only more common thanks to humans’ environmental destruction. It’s too late to keep tinkering with the status quo. It’s time to completely overhaul the way we value those who do the most vital, life-giving work.

Who are Canada’s care workers?

There are roughly 25,000 migrant live-in care workers working in Canada today, according to a Migrant Rights Network report released in October 2020. This number doesn’t even include migrants working in long-term care facilities, as personal support workers, nurses, occupational therapists, custodians, educational assistants, or support staff. This number would balloon if those workers were accounted for.

Canada’s agricultural sector, too, is highly dependent on Temporary Foreign Workers (TFWs) because they make up over 20 per cent of the sector’s workforce, according to an April 2020 Statistics Canada report. When COVID hit North America and migrants were barred from re-entering the country to return to work, Canada’s entire agricultural sector fell to its knees overnight. The outcry was so swift and unequivocal that you may not have even caught it in the news when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau quickly reversed his decision.

It takes a massive amount of money and effort to set up and maintain a system that allows Canada to maximize the exploitation of migrant workers’ labour while minimizing the protections that the state must provide them.

If migrant workers are the people keeping us alive through catastrophes like COVID-19, then why are we so quick to exclude and dehumanize them? This exclusion looks like an impossibly complex, punitive, and high-stakes immigration system.

Live-in caregivers, for example, typically come to Canada on closed work permits tied to one employer. To apply for permanent residency, they need two years’ work experience – but if they are fired or quit they cannot work elsewhere. They also live in the homes of their bosses, who hold the fate of their citizenship in the palm of their hands. This makes it incredibly difficult for migrant caregivers to change employers or escape abusive bosses – many have reported wage theft during the pandemic. Migrant farmworkers, too, have their visas tied to their employer, meaning they can’t change farms once in Canada. Many live in horrific conditions, are paid unlivable wages, and extorted for thousands of dollars. Justicia 4 Migrant Workers has reported stories of workers being threatened with deportation for standing up for their labour rights, losing limbs to machinery, and being trapped in cyclical abuse at the hands of people in control of their pathways to safety.

Last year, the Migrant Rights Network reported that police officers across Canada make over 10,000 phone calls a year to immigration enforcement.

These immigration systems aren’t simply archaic or bureaucratic; migrant workers’ exclusion is deliberate. In the 1960s and 1970s, Canada started giving out temporary work permits designed to allow Canadian employers to hire migrants for specific jobs, without giving those workers access to permanent residency. It takes a massive amount of money and effort to set up and maintain a system that allows Canada to maximize the exploitation of migrant workers’ labour while minimizing the protections that the state must provide them. This money goes toward enforcing arbitrary and punitive borders at every point-of-access to public services. Whether it’s transit cops demanding to see your passport, traffic police demanding your work permit, or being asked to prove your permanent residency when reporting a sexual assault, migrants are constantly policed and surveilled. Last year, the Migrant Rights Network reported that police officers across Canada make over 10,000 phone calls a year to immigration enforcement. We spend billions on policing the people who keep our children cared for and our elderly safe, instead of welcoming our community members as full citizens.

Unpacking the extent to which our understanding of borders, policing, and xenophobia have warped the way we value care work, and those who carry it out, is a massive undertaking. But it’s one we must prioritize if we are to un-make the mess we’re in.

Against scarcity, toward abundance

While I was a migrant rights organizer in Tkaronto, the number one training we did was to educate migrants on how to access services like health care – which they have a human right to – without fear. At the same time, the number one question I was asked by the media was, “but do you think these people should get access to services Canadians barely have access to?” These journalists argued that we had no other option than to deport, exploit, incarcerate, and exclude migrants, because Canada doesn’t have enough money to do anything else.

For too long, we’ve been sold a carefully-constructed political narrative of scarcity, and been told that its only logical solution is austerity and policing. This lie has permeated deep into what we believe we’re fighting for and against, but when you follow the money, it starts to dissolve. I’ve already explained to you that Canada’s regime of border policing is incredibly expensive. We know that the money to build a better world exists – it’s just not being put to the right use. Right now, it’s tied up in police budgets and rich people’s tax havens.

For too long, we’ve been sold a carefully-constructed political narrative of scarcity, and been told that its only logical solution is austerity and policing.

Nationwide, we spend roughly $15 billion on all levels of policing – municipal, provincial and federal. This excludes the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and government offices like Immigration and Customs. The average cost of incarceration of a human being in this country between 2015-2016 ranged between $51,830 and $203,670 per person. Most folks in our prisons are non-violent poor people who are struggling to live and can’t afford to make bail.

Canada is also home to the fifth most ultra high net wealth individuals on the planet. Due to and since the beginning of the global pandemic Canada’s 20 top billionaires raked in $37 billion in additional wealth, according to a September 2020 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA).

So how do we free up this money, and put it toward the urgent task of providing life-saving necessities for everyone in Canada? The answer is two-pronged. First, divest from the systems that cause death and destruction, like policing, prisons, and resource extraction.

Second, invest in building a fair and safe world for all: health care, food security, affordable housing.

The CCPA calls for a one-time emergency wealth tax, and recurring annual wealth tax. It’s a clear, ethical, and economically sound solution we should have acted on at the beginning of this crisis. This type of tax is popular with the public – of 1,660 Canadians polled by Abacus Data, 79 per cent supported the idea of a 1 per cent wealth tax on fortunes of $20 million or more – but it is, of course, unpopular with the ultra-rich and the politicians they bankroll.

Migrant workers are building our collective futures

At 3 degrees of global warming, hundreds of millions of people will be displaced as rising seas swallow coastal cities. We are on track for 4 degrees of warming in our lifetime. The debate we are having is no longer about if we can stop global climate change. We are debating who deserves to survive, and the answer must be nothing less than all of us. Migrants are our community members. Always have been, always will be.

The pandemic has helped us see that caring for each other is not just necessary, and not just morally right – it’s also good for the planet. In contrast to higher-paid and -valued jobs like resource extraction or financial speculation, which pursue relentless growth for growth’s sake, care work is low-carbon work that builds the foundation of a new, more sustainable, and more just world.

We have precious few years left to limit global warming and mitigate climate catastrophes. We gutted the social institutions and devalued the migrant labour that could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives in a pandemic – we did this both months before the crisis began, and steadily for decades prior. We cannot afford to make the same mistakes again. The time is now to move toward an economy based on the valorization of care work, public ownership of our social institutions, strong unions, solidarity cities, and status for all. It’s not only what will begin the repair of our disintegrating social fabric; it will prepare us for the looming climate crisis.

In contrast to higher-paid and -valued jobs like resource extraction or financial speculation, which pursue relentless growth for growth’s sake, care work is low-carbon work that builds the foundation of a new, more sustainable, and more just world.

It will take nothing short of a revolution. Sector by sector, in the streets, in our homes, in our hearts and minds, we will breathe life, through sheer force of will, into the world we must build in order to survive. As a favourite community organizer of mine once said of massive social movement wins in times of shock and revolution, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” We deserve a world where police wither away, and are replaced with care workers entrusted with health, well-being, and safety. We deserve a world without billionaires, where all members of society are paid fairly and treated with dignity.

As my comrade Syed Hussan said in another article in Briarpatch, at another moment in our history, “The work of first becoming aware of, and then removing the blockages in our imaginations has to happen in multiple avenues of our lives at once. It is possible; it is certain. Freedom is coming.”

We all rely on lifegiving and live-sustaining care work in one way or another. We deserve a society that values those who provide care work as well as all of us who access it.

It is possible; it is certain. Freedom is coming.