In our most recent reader survey, we asked readers how they first learned about Briarpatch. Whether it is a sign of the loyalty of our readership or the advanced age of the magazine I don’t know, but a whopping 26 per cent checked the box “It’s been so long I can’t remember.”

I’m young enough that I happen to be among the 74 per cent of Briarpatch readers who does remember his first encounter with the magazine. It was a softball tournament, of all places, circa 1985. I don’t remember anyone reading Briarpatch in the stands, but the magazine (and its need for cash) was the reason we’d all gathered that summer day; the tournament was organized as a fundraiser for Briarpatch. My dad’s workplace had entered a team — the Churchill Park Green Thumbs — and I’d tagged along to cheer them on.

I was seven years old — you could say I was thrown into the briarpatch at an early age. Growing up, the magazine was a familiar presence around the house. Five years its junior and admittedly not the most attentive reader for the first several years, I must say I’m poorly equipped to reflect on 35 years of Briarpatch Magazine in this, the 35th anniversary issue. But it’s a story that bears retelling, so I’ll try to do it justice in the limited space available, cautioning that many important details have been left out.

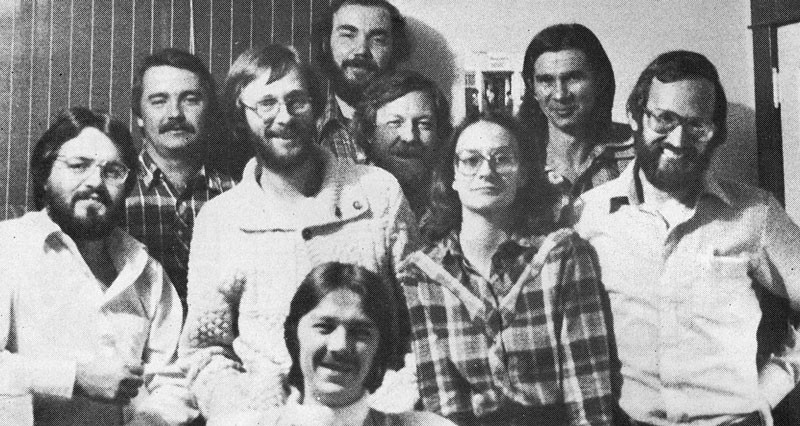

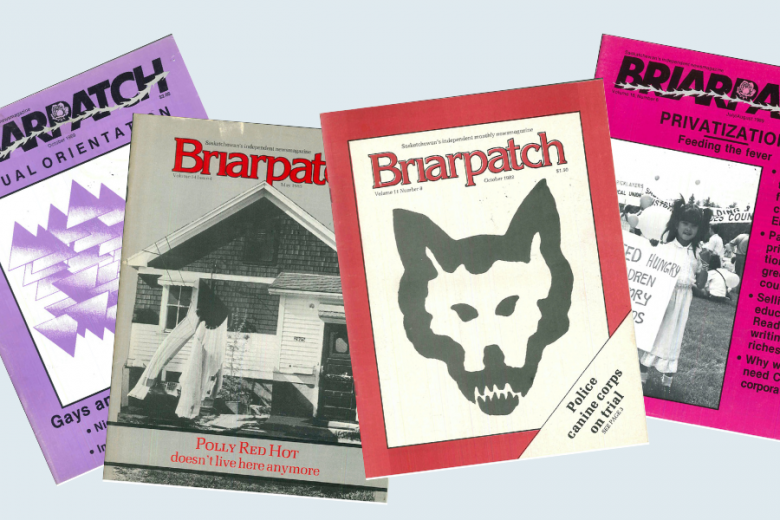

Briarpatch launched in 1973 as a newsletter of the Saskatchewan Coalition of Anti-Poverty Organizations (allegedly derived its name from a grudge with a social services director named Brierley). It was a grassroots effort, constantly on the verge of bankruptcy, and driven by a fierce commitment to popular empowerment. “In those early years, we were mostly concerned with helping people gain self-confidence and become articulate in print and to become conscious of organizing and supporting each other in challenging the status quo,” reminisced founding editor Maria Fischer in a 20th anniversary retrospective. “We would hold back an article written by us if it meant we would have no space for an article that a group needed to circulate on a particular struggle.” The newsletter was born from, and thrived on, the “commitment that the Briar Patch belongs to everyone who struggles against oppression,” said Fischer.

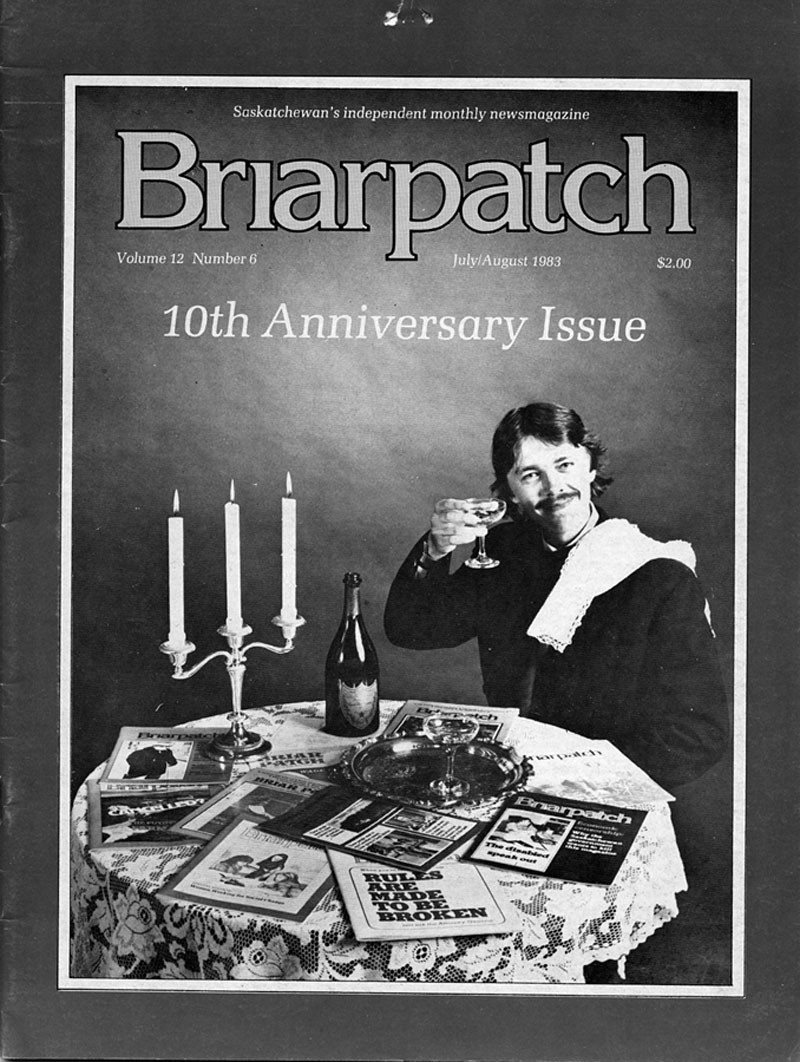

By the late 1970s, Briarpatch had evolved from a “stapled-in-the-corner anti-poverty newsletter” into the independent, subscription-based, insufferably cheeky magazine it is today. Here’s how former editor Marian Gilmour (1977-79) tells it: “We had a vision of an activist publication — one that provided critical, alternative, topical information in a friendly, accessible yet irreverent format.” Billing itself variously as “the voice of Saskatchewan people,” “Saskatchewan’s independent newsmagazine” and — my favourite — “a champagne magazine on a beer budget,” the raging little rag grew to play a vital (albeit marginal) role in Saskatchewan’s social fabric, producing investigative, muckraking, risk-taking journalism and analysis, both reporting on and participating in Saskatchewan’s social movements of the day.

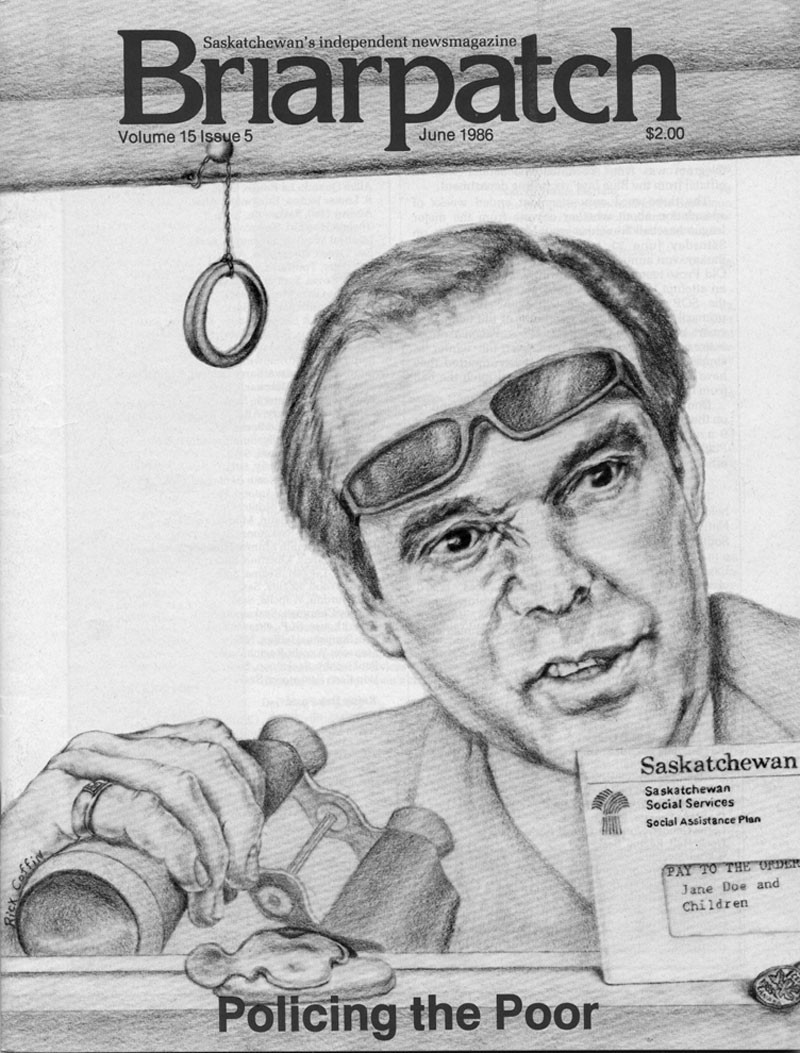

The magazine hit its stride not a moment too soon. When Grant Devine’s Conservatives swept to power provincially in 1982 and launched into their programme of social spending cutbacks and privatization, Briarpatch was there as both a watchdog and a rallying cry, documenting the excesses and galvanizing a grassroots opposition to the assault.

Briarpatch was vital to the growing opposition, playing an important role in the larger movement. But don’t take my word for it. As conservative pundits Paul Jackson and Don Baron would have it, writing in their now-laughably inflammatory 1991 book Battleground: The Socialist Assault on Grant Devine’s Canadian Dream:

“Saskatchewan is home of Brierpatch [sic], one of Canada’s more curious publications, a monthly magazine published as a sort of heartbeat of the socialist cause. . . .

“Anyone who thinks Brierpatch [sic] is simply an aimless outpouring by a few dreamers doesn’t understand today’s world of ideas and the deadly earnest business of influencing the public agenda. This is a flag-ship paper. Its thrust is masterminded and orchestrated for greatest possible effect.”From the sounds of it, mighty Briarpatch had the poor capitalists quaking in their proverbial loafers.

Whatever modicum of influence the magazine may have had while the “socialists” were in opposition, Briarpatch was soon cast adrift in a sea of compromise after Devine and his cronies were thrown overboard in 1991. When the third-way NDP of Roy Romanow returned to power and further slashed spending to deal with the deficit they’d inherited, the provincial Left quietly split into two camps — the work-with-the-NDP crowd and the work-outside-the-NDP’ers.

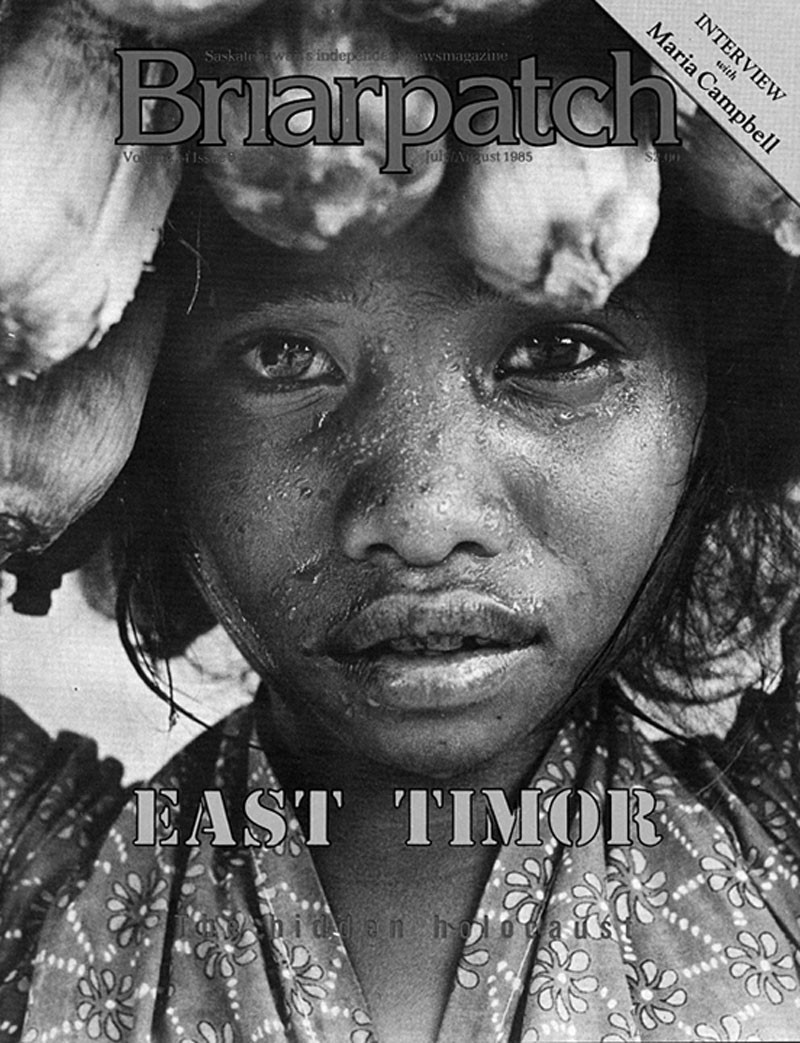

Without the unifying power of a common enemy from which to draw energy and purpose, Briarpatch increasingly began to extend its focus and its readership beyond Saskatchewan’s ruler-straight borders, joining other left-leaning magazines like This and Canadian Dimension in providing an alternative perspective on national and international issues to Canadians from coast to coast, while still endeavouring to speak for, and from, Canada’s wheat heart.

By 2004, the transition was complete: for the first time, there were more Briarpatch readers in B.C. and Ontario combined than in Saskatchewan, a shift that presented a new challenge for the magazine as it spoke increasingly to its national readership while still trying to serve the media needs of its long-time Saskatchewan supporters.

This challenge has grown more pressing since the right-wing Saskatchewan Party defeated the somewhat less right-wing NDP in last November’s provincial election and launched an all-out assault on the rights of workers. In some ways it feels like a return to the climate of the Devine years; Briarpatch’s staff and board are presently exploring how best to harness the organization’s legacy and assets to fill the role it once filled while continuing to serve the magazine’s nationwide readership. Rumours abound that a sister publication to the magazine is in the works — a news tabloid focused on Saskatchewan politics. In many ways, this would be a much-needed resurrection of Briarpatch’s one-time role as “Saskatchewan’s independent newsmagazine.”

For now, suffice it to say that the next 35 years should prove at least as dynamic and interesting for Briarpatch as the last 35 have been. I hope you’ll stick around for the journey.

In closing, would you indulge me a moment and pour yourself a glass of champagne, beer or whatever you’ve got handy? (I’ll wait…. Okay, ready?) Readers, please raise your glasses to Briarpatch at 35. In the words of that traditional Scottish toast:

May the best you’ve ever seen

Be the worst you’ll ever see;

May a mouse ne’er leave yer girnal

Wi’ a teardrop in his e’e.

May ye aye keep hale and hearty

Till ye’re auld enough tae dee,

May ye aye be just as happy

As I wish ye aye tae be.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)