The second-largest chain of newspapers in Canada, Torstar, is set to change hands this month to a new company, Nordstar, owned by a couple Conservative-donor businessmen. No one has put in a higher bid to try to buy Torstar, nor indicated they intend to.

I argue here that someone should. Foundations, unions, progressive pension funds, and wealthy individuals should seriously consider making a bid for Torstar now, given the potentially enormous social impact. And failing that, these institutional players should prepare for the next time an opportunity like this comes around.

For a relatively low price of approximately $60 million, one of the big seven media companies – the second biggest newspaper company – could become a force that disrupts the status quo consensus in Canada.

For the last month, I’ve been talking to media experts and a few investors, looking closely at Torstar’s finances and business model, and trying to drum up interest in buying Torstar. While there have been some promising conversations, nothing concrete has coalesced. If someone wants to make a bid, it needs to be before the Torstar shareholder vote on the deal on July 21, 2020. (Disclosure: I own $2,480 in Torstar stock as of writing.)

In this article, I’ll first look at the potential dangers in the Nordstar sale. Then I’ll examine why Torstar, one of the seven major media players in English Canada, is so important to how we consume information and talk to each other from local to national levels. Next I’ll argue that while Torstar is not very progressive or left-wing now, it could be. Finally, I’ll look at how and why Torstar could be a good investment – despite the skepticism from the business community – if you’re not looking for huge profits.

From Torstar to the unknown Nordstar

Torstar’s flagship Toronto Star newspaper (with thestar.com online editions for seven major cities across the country), along with the Hamilton Spectator, Waterloo Region Record, St. Catharines Standard, Niagara Falls Review, Welland Tribune, Peterborough Examiner, around 50 per cent ownership in Canadian publication of the Sing Tao Daily, around 70 community papers, and all Torstar’s investments, assets, and liabilities are being sold for $52 million. The buyer is Nordstar, a new company owned by two Conservative donors, Jordan Bitove and Paul Rivett. The owners are Ontario residents, but they incorporated Nordstar in Manitoba. Their bid is fully financed through a loan from Canso, the same lender who owns about $95 million of debt in Postmedia, the country’s largest newspaper chain.

These facts raise two immediate concerns. One is whether Nordstar and Canso are considering more mergers between Torstar and Postmedia. In 2017, the two giants traded a total of 41 papers, and quickly shut down 36 of them. A similar move could mean a significant loss to local news. Nordstar maintains they intend to keep the daily papers like the Toronto Star, but are less clear about the 70 or so community papers, with the Globe and Mail reporting Nordstar plans to sell off non-core assets.

Once they own the paper, Nordstar has the power to change its mandate and install a new publisher and by extension a new editor-in-chief who could take the paper to the right.

The second concern is whether we’ll see editorial changes under the new ownership. The buyers say they’ll follow the existing Atkinson Principles, a set of progressive editorial principles meant to guide the paper, and that they see a market for a liberal paper. This is a nice enough statement, but coming from Conservative donors it should be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism. And buyer Paul Rivett’s donations to Doug Ford in 2018 and far-right xenophobe Maxime Bernier in 2017 and 2018 don’t inspire confidence.

Once they own the paper, Nordstar has the power to change its mandate and install a new publisher and by extension a new editor-in-chief who could take the paper to the right. Or they could try selling the Toronto Star to Postmedia; if that were to happen, the new Star would likely run Postmedia’s conservative editorial line, as is the case with Postmedia’s papers in most major cities across the country.

We can try to pressure the Conservative-supporting owners to not take these kinds of actions once they own the paper, but that raises the question: why accept Conservative-supporting owners of a supposedly progressive newspaper in the first place?

Torstar is important – very important

Torstar, because it is so large and established, is a very important institution in shaping what we talk about in Canada, and how.

There are, by my count, seven major media players in English Canada, and, measured by revenue, they are all hundreds or a thousand times larger than most independent media in the country. Torstar is one of these seven which produce enough news and have enough readers that they consistently shape conversations at the national, provincial, and local levels.

There are three newspaper companies among the seven majors in English Canada: Postmedia, Globe and Mail, Torstar. Then there are four TV and radio companies: CBC, Bell (CTV & iHeart), Corus/Shaw (Global), and Rogers (CityTV, OMNI, radio stations). To a large degree, newspapers do original investigations, and then those are repackaged and commented on in radio and TV, thereby setting the mass media conversation. Today, the radio stations and TV channels increasingly do investigations and original reporting, and produce text reporting for online consumption, but the old divisions persist whereby newspapers often break big news. Think of the Globe and Mail breaking news of the Trudeau government’s SNC-Lavalin scandal.

When people get and talk about “the news” – like what a politician said, what good or bad action a company took, what a court decided in a case – it is usually from these seven.

Torstar is in the middle of the paper companies by size, with $479 million in revenue in 2019. Postmedia, meanwhile, had $620 million in revenue, and the Globe and Mail’s finances aren’t made public, but its revenues are likely significantly smaller than Torstar’s.

(You could argue that the Canadian Press is an eighth major player, as all seven buy stories written by the Canadian Press every day. But the Canadian Press is owned by three newspaper companies Torstar, the Globe and Mail, and major Quebec paper La Presse. There are a few other big players, like FP Newspapers ($63 million revenues in 2019) which publishes the Winnipeg Free Press among others, TVO ($67 million revenues in 2019), and APTN ($50 million revenues in 2019). The latter two get the bulk of their funding from government and because of government regulations, respectively. And while all three do crucial work, their budgets and reach are much smaller than the seven majors.)

The big seven shape mainstream discourse in Canada. When people get and talk about “the news” – like what a politician said, what good or bad action a company took, what a court decided in a case – it is usually from these seven. And these seven decide who gets a big platform to comment on the news. When we hear five white people comment on whether there is racism in Canada on the evening news, that is the result of choices made by the media majors.

In most instances, news is framed in a way that assumes the maintenance of the current status quo. Canada’s jurisdiction over the land, despite its violation of Indigenous treaties or in absence of treaty, is rarely questioned. Despite Canada’s land claims being based on the racist Doctrine of Discovery and Papal Bulls, mainstream media by default treat Canada as the rightful authority over these lands. But when Indigenous Peoples assert their claims to their land, mainstream media question those claims, while assuming Canada’s are valid.

These media companies take an editorial position whereby “neutrality” and “objectivity” are equated to a defense of the status quo. This style of coverage, of course, favours the already powerful.

Likewise, major media tend to maintain consensus for an economy where investors and an executive class make millions, while workers labour for much smaller share of the wealth, with minimal protections. When people question the capitalist system, they are questioned by media. The media rarely question capitalism itself, especially not in day-to-day coverage of the news.

These media companies take an editorial position whereby “neutrality” and “objectivity” are equated to a defense of the status quo. This style of coverage, of course, favours the already powerful. It favours the colonial power, Canada, over First Nations; it favours investors over workers; it favours white people in positions of power over BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour); it favours cis over trans people; and it favours men over women.

Through dozens of articles and TV and radio segments every day, these media companies, Torstar included, reinforce these power relations. In some cases, it is part of their mandate, like with Postmedia, which was formed to disseminate conservative ideas and views. For others like Torstar, while claiming to be progressive, they too often wind up taking the side of colonial, pro-business, anti-environment interests. Take, for example, the time the Toronto Star editorial board repeatedly came out in favour of the Coastal GasLink fracked gas pipeline, which is being built without Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs’ consent, and at RCMP gunpoint.

Torstar is big – really big

This mainstream media consensus has for decades been challenged by independent media like Briarpatch, the Media Co-op, rabble.ca, now-defunct Redwire, and more recently by a newer generation of digital players, including the National Observer, Rank & File, WindSpeaker.com, The Narwhal, and many others.

As exciting as the new generations of media organizations are, and though they do fantastic investigative reporting at times, they operate at nowhere near the scale of Torstar.

While social media has changed the nature of (breaking) news, commentary, gossip, and so on from a race to publish tomorrow to a race to publish instantly, the seven mass media companies are still the ones who take the breaking news and communicate it more widely.

Why? Because they have subscribers, which means revenue, and because they are still relatively widely trusted.

Torstar, despite contracting in recent years, is still absolutely massive compared to any independent media in English Canada.

This is not to deny the crucial importance of independent media, which fills so many gaps in coverage and analysis left by these mainstream outlets. Trust me, I worked as publisher of Briarpatch for three years and write mainly for small, independent outlets willing to challenge the status quo; I get it.

But Torstar, despite contracting in recent years, is still absolutely massive compared to any independent media in English Canada. In 2019, not a great year for Torstar, it had annual revenues of $479 million dollars. Briarpatch breaks $200 thousand in a good year. I hear The Tyee, one of (if not the most) successful independent outlet in English Canada, has annual revenues around $1 million. Canadaland, one of the most popular podcast sites, which also has text articles, may get close to $400 thousand in subscriber revenue annually, and has a similar quantity of advertising revenue on top of that, but probably hasn’t broken $1 million. rabble.ca, at one time the leading online labour-friendly publication in the country, had annual revenues of $352 thousand last year. Torstar revenues were over 1,350 times that.

By my rough math, the annual revenues of all the somewhat-to-actually left independent media in Canada probably wouldn’t break $10 million. And due to conflicts between them (some petty, some justified) and because they’re sometimes vying for the same subscribers, the independents rarely pool their resources or collaborate. Meanwhile, Torstar brings in $119 million from subscription sales to its daily papers alone.

It is one of the very few media companies in English Canada to consistently – every single day – set which important issues we talk about, and how they’re framed.

Building up to that level is not something independent media organizations have been able to do yet. (Though, to be fair, no one has invested $52 million in an independent media company in Canada.)

This is not to disparage independent outlets, but to point out that Torstar has the size and capacity to do things smaller players can’t. Who has a reporter assigned to each of the municipal, provincial, and federal governments, to cover meetings, announcements, and do investigations? The majors, and very few of the independents. Who has a courthouse reporter? The majors. Who follows government officials on overseas trips for conferences and diplomatic meetings? The majors, though this is becoming less and less common. Who invests in long-term investigations into corporate and government negligence, malpractice, etc.? The majors consistently, and independents when they can find the resources.

More than 20 years into the shift to the internet, Torstar still has the size and visibility the independents don’t, at least not yet anyway. It is one of the very few media companies in English Canada to consistently – every single day – set which important issues we talk about, and how they’re framed.

Torstar is hardly a progressive paper – but it definitely could be

Are there problems with Torstar as it currently exists? Of course.

As briefly mentioned earlier, the majors are consistently pro-business and anti-worker, are deeply colonial and anti-Indigenous, are often anti-Black and racist, gloss over environmental issues, and engage in poor-bashing. (So are some of the independents, to be honest). Despite having many stellar reporters and editors on staff, Torstar too often takes these stances. In addition, ownership, management, and those in positions of power remain overwhelmingly white.

The editorial problems stem mainly from the old Torstar business model, and from management.

Torstar papers used to make most of their money from advertising, and the smaller community papers (not the big dailies) still do. In the past and still today to a degree, sections of the paper read like fluff pieces for advertisers. As former Toronto Star reporter Walter Stewart wrote in his 1980 book, Canadian Newspapers: The Inside Story, the Star’s Real Estate section was notoriously guilty of this, with stories critical of developers almost never making it to print – and when they did, the reporters and editors would be reprimanded by management for putting advertiser relationships in jeopardy.

But by setting a new direction, funding the right bureaus, making new hires, and making some smart but tough choices about cuts, Torstar’s papers could shift their focus and analysis.

There have been issues with Torstar’s management and ownership over the years, who have overseen a precipitous decline in value and revenues and made millions for themselves in the process. But that story could fill a book, and is too long to get into here.

The important thing is that the paper, with a change in ownership, could be significantly more progressive and representative of the communities it is in.

But by setting a new direction, funding the right bureaus, making new hires, and making some smart but tough choices about cuts, Torstar’s papers could shift their focus and analysis.

Workers’ papers have existed in the past, distinct from union newspapers or newsletters, but are now a distant memory. The core idea is that the paper is from the perspective of workers, not big businesses and the governments which govern for them. A modern version of a worker’s paper, which truly comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable, is possible. There are so many people in Canada who are not benefiting from the status quo, and none of the major media reflect their interests and perspectives. There is an opportunity.

A modern version of a worker’s paper, which truly comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable, is possible.

Torstar was valued at $1 billion in early 2011, a legitimately out of reach price for most left-leaning institutions and coalitions. Now it is being sold for $52 million (and the buyers are borrowing the money, not even putting up their own). At that price, Torstar is within reach for numerous organizations and individuals or groups of individuals. For example, the Atkinson Foundation, which was started with money from Joseph Atkinson, former editor and publisher of the Toronto Star, has $90 million in investments. And that’s a small-to-medium sized foundation. The Ontario Teacher’s Pension Fund (OTPP) has around $200 billion in investments. There are also over 10,000 individuals in Canada with over $30 million.

Torstar is a decent investment – or at least better than you’ve heard

If you agree the current deal is troubling, and that Torstar is important and has potential, the remaining question is whether Torstar is a good investment at this price.

Really getting into the finances is beyond the scope of this piece, but I have prepared a financial summary based on publicly-available data, available here. For the most accurate picture, a serious potential investor should contact Torstar, say they are considering putting in a bid, and ask to see the internal, up-to-date finances.

In brief, based on available info, the answer is that Torstar has elements of both a good and bad financial investment.

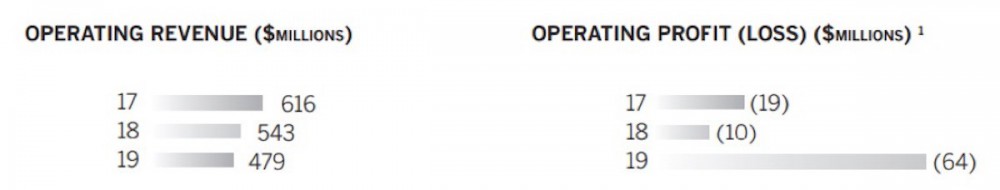

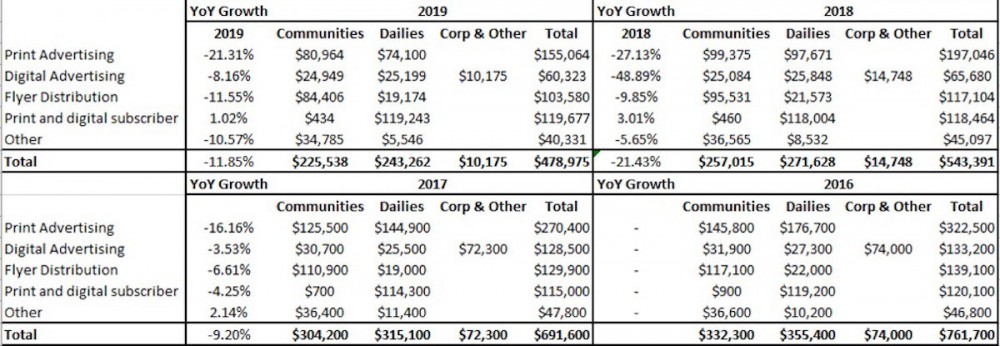

First, the bad news. Revenues keep going down, mainly a result of declines in advertising revenues of tens of millions of dollars a year, and the company operates at a loss. Revenues went from $616 million in 2017, to $514 in 2018, to $479 in 2019. Operating losses were $19 million in 2017 (the last year of the disastrous Star Touch project), $10 million in 2018, and $64 million in 2019.

To cover these losses, they’ve sold assets, like the Hamilton Spectator building for $25.5 million this winter. There is also a pension liability of $54 million. So, while revenues are going down, assets are being sold off. If the trend continues, the company will need to keep selling assets, and then go into debt to keep operating.

The good news is that Torstar has no debt, appears to be cash rich, still has valuable assets, has had stable subscriber revenue the last few years, and the selling price is relatively low.

All that cash ($69.5 million plus $100 million plus $22.9 million) comes out to $192.4 million, on top of full control of the daily papers and their assets.

Unlike Postmedia, Torstar has no debt on its books, which means no interest payments. Also, taking Torstar private can mean no dividend payments. Even though Torstar was losing millions a year, it was still paying out around $8 million a year in dividends to shareholders, until fall 2019.

And, as of March 31, 2020, Torstar had $69.5 million in unrestricted cash sitting around, according to a report by Blair Franklin Capital Partners, commissioned by Torstar.

The Nordstar plan, according to a recent Globe and Mail story, is to sell off non-core assets for $100 million. This includes the 56 per cent stake in VerticalScope, a digital media company which “operates more than 1,500 user forums and premium content sites,” according to Torstar. Torstar bought their stake in VerticalScope for $200 million in 2015.

In addition, Torstar is waiting on $22.9 million in tax credits. All that cash ($69.5 million plus $100 million plus $22.9 million) comes out to $192.4 million, on top of full control of the daily papers and their assets. From there, Nordstar can put $42.6 million aside to cover the company’s existing pension liability (or not, if they think they can cover the yearly pension cost from operating revenues); use another $23.3 million to cover a planned restructuring; pay themselves back for the purchase price of $52 million; and still have $74.5 million in cash to invest in the papers, to cover budget shortfalls, or to take for themselves as owners.

Put another way, if that all goes according to plan, Nordstar can pay off the $52 million it borrowed, and have $74.5 million in cash to play with. Not a bad deal.

Torstar is unlikely to be generating huge profits in the near term, but neither is it the financial lost cause some claim it to be.

The other good news for Torstar is its subscriber revenue. Ad revenue is likely to keep declining by tens of millions until it reaches a stable level, though what that level is will be affected by whether the Canadian government starts regulating Facebook, Google, Twitter, and others. But print and digital subscriber revenue has been mostly stable the last four years, and even growing. From $119 million in 2016, to $114 million in 2017, to $118 in 2018, to $119 in 2019.

If Torstar focuses on subscriber revenue, and not chasing ad revenue, it has a chance to grow subscriber revenue, which can – in part or in full – make up for declining ad revenue. Chasing ad revenue, though, may be tempting in the short term. But as seen with media like Postmedia, VICE, NOW Toronto and the Georgia Straight, chasing ad revenue often leads the company into advertorial territory, and the blurring of editorial and advertising. Media Central Corp, the new owner of NOW Toronto and the Georgia Straight, recently announced it was blending advertising and editorial departments. This sort of approach doesn’t work for maintaining and growing a subscriber base.

So, with stable and possibly growing subscriber revenue, cash on hand, and assets, Torstar has some ability to weather what it is going through, namely watching its old base of advertising revenue dry up. Torstar may operate on smaller revenues in the future (or it could grow). But even at a level of around $100 million in subscriber revenue, that is nothing small, and provides resources to work with. In sum, Torstar is unlikely to be generating huge profits in the near term, but neither is it the financial lost cause some claim it to be.

Why now? And if not now, when?

From all of this, two things are apparent.

One is that even with millions of dollars of investment, it would be very hard to build something new that could have the reach and revenue streams that Torstar already has. It’s possible, certainly, and worth doing regardless of what happens with Torstar, but building up to that scale is very hard.

The second is that, for a relatively low price of approximately $60 million, one of the big seven media companies – the second biggest newspaper company – could become a force that disrupts the status quo consensus in Canada, and fundamentally change the conversations we are having.

Think of what Postmedia did for the right and you can see some of the possibilities for the left. Postmedia holds a consistently right-wing, often racist, line, and pulls the whole country and every political party with it to the right. Every single day. Imagine if Torstar did that, not for pro-business liberals, but for workers, for Indigenous rights, for environmental issues, and more.

The big seven companies rarely get sold. Several of them are privately controlled, like the Globe and Mail (Thompson family) and Rogers (Rogers family), so they may never be sold off. The CBC, being the public broadcaster, will also likely not get sold off. This is a very rare opportunity. One of the majors is being sold, and it also happens to be the only one that has an explicitly progressive mandate.

Postmedia holds a consistently right-wing, often racist, line, and pulls the whole country and every political party with it to the right. Every single day. Imagine if Torstar did that, not for pro-business liberals, but for workers, for Indigenous rights, for environmental issues, and more.

In the ideal scenario, a buyer would treat this more as a donation than an investment by turning the organization into one non-profit or a network of non-profit papers, and taking a loss for tax purposes. The Desmarais family did this recently with La Presse. It could be done in such a way that the board or boards of directors are representative of the communities they operate in, rather than reproducing enclaves of the rich and powerful.

To summarize, we can watch Torstar go to a couple conservative donors, financed by the same lender as Postmedia, and cross our fingers that (at best) Torstar will stay the same, and that it won’t be merged with Postmedia or otherwise become a chain of right-wing rags. Or one or more people or organizations can make a bid, quickly, for Torstar.

And if Torstar goes to Nordstar, hopefully progressives will pay attention to the future of media, and be ready when the next opportunities arise, in order to play a role in the future of media. Otherwise, capitalists and conservatives will keep running the show.