With protests erupting across the United States, Canada, and around the world in response to police killings of Black and Indigenous people, Canadian labour unions released a series of strong statements this month against anti-Black racism, racial injustice, and police violence. But we also need to have an urgent conversation about police in the labour movement.

If we are seriously committed to protecting Black and Indigenous lives, policing can’t just be tweaked, it must be abolished and replaced with a new approach to community safety. The role of the police in our society is fundamentally anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, and anti-worker. As trade unionists, our efforts to dismantle systemic racism must include abolishing police unions and the police from our own unions.

Shouldn’t all workers have the right to unionize?

Yes, all workers should have the right to organize a union, and many do not because it is illegal or impractical under current labour laws. For example, migrant farm workers and domestic workers are denied the right to form a union in Ontario. We organize against these racist exclusions because they are unfair, divide workers, and weaken the labour movement.

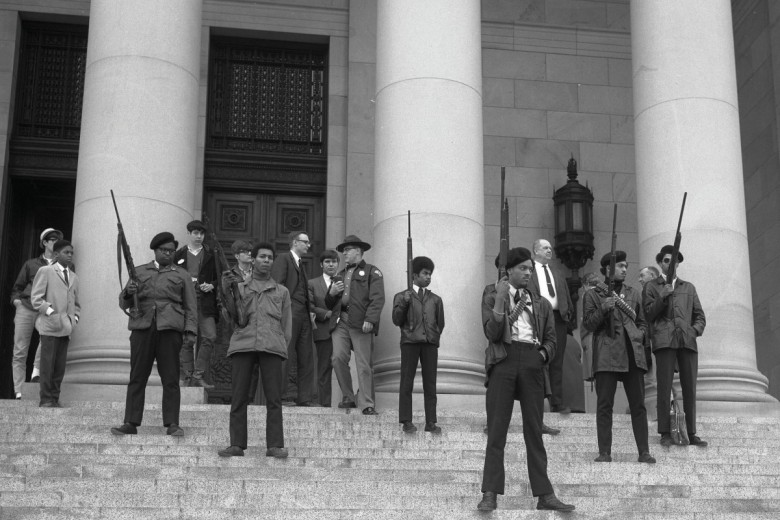

But police are not workers, not in the way that matters most. Workers are members of the working class, while the police were founded to serve and protect the interests of the ruling class: putting down strikes by workers, capturing runaway slaves, and pushing Indigenous people off their lands.

Police perform the same function today. Black and Indigenous people continue to be killed by the police at extremely disproportionate rates. A study by the Ontario Human Rights Commission found that a Black person in Toronto is 20 times more likely to be fatally shot by the police than a white person. In the past two months, at least nine Indigenous people have been killed by Canadian police or died while alone in their presence.

Workers are members of the working class, while the police were founded to serve and protect the interests of the ruling class: putting down strikes by workers, capturing runaway slaves, and pushing Indigenous people off their lands.

In February, RCMP officers raided Wet’suwet’en territory to arrest Indigenous land defenders for protecting their unceded land from Coastal GasLink’s pipeline project. Even after being exposed, the RCMP continues to collude with the energy sector to surveil Indigenous activists.

When the Co-op Refinery Complex obtained an injunction to prevent locked-out members of Unifor Local 594 from picketing in Regina, the Regina Police Service were sent in to enforce the ruling by fining and arresting workers. Outside of Regina, the RCMP enforced the likely unconstitutional injunction with such gusto that they even threatened to arrest picketers at locations not included in the order.

Up until 2015, the RCMP were ineligible to unionize, unlike the rest of their police counterparts in Canada, who are able to form unions and collectively bargain, but not go on strike. The Canadian Police Association, along with the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC), intervened in a Supreme Court of Canada case to argue in favour of RCMP officers gaining the right to form a union.

The Government of Canada argued that having the right to unionize could impair the “stability” and “neutrality” of the RCMP. In its ruling, the Supreme Court found no merit in the government’s argument that the right to unionize would weaken the police’s allegiance to the ruling class. If the Supreme Court could see this, it begs the question: What did the CLC and PSAC think the labour movement stood to gain from Mounties winning the right to unionize?

Why we need to abolish the police in our unions

As a result of the Supreme Court’s January 2015 decision, 20,000 RCMP officers and 10,000 civilian employees became eligible to unionize. In 2018, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) announced that they had successfully organized a unit of nearly 1,300 RCMP telecom operators and intercept monitor analysts, an effort that started in 2016.

This organizing “victory” prompted a backlash from CUPE’s existing membership. A group called Cops out of CUPE formed and brought motions to the union’s provincial conventions in 2018 and 2019, and to their national convention in 2019, asking CUPE to reject the inclusion of state security forces in the Canadian labour movement. The national motion asserted that CUPE’s unionization of state security forces was at odds with the union’s opposition to the Bill C-51 and C-59 spy bills and its solidarity statements with the Wet’suwet’en Nation and Movement for Black Lives. It also noted that these forces “have surveilled and repressed worker and justice movements including but not limited to current and previous members of CUPE.”

"My family and I have experienced a lot of harm at the hands of the police. We can't let this issue go. The statements by our unions need to be complimented by concrete action."

This grassroots effort by rank-and-file activists forced an important conversation about the ethics of organizing the RCMP. Cops out of CUPE was started by Indigenous CUPE members, and gathered endorsements from a number of locals, the provincial Young Workers Committee, and the Ottawa CUPE District Council. So far, their motions have received a cool response from the leadership and did not garner enough support to pass.

Gizem Çakmak attended the national convention as a delegate with CUPE 3903, one of the locals that endorsed the campaign. She recalled a member of CUPE's national executive speaking against the motion by emphasizing that "all workers have the right to unionize" and making an emotional appeal to the sexual violence faced by women workers in state security forces. But Çakmak asks what organizing the RCMP means for people like herself who come to unions as a refuge from state violence and a site for organizing against it. "As an immigrant worker from Turkey, I'm not Black and I don't experience anti-Black racism in the way that other CUPE members do, but my family and I have experienced a lot of harm at the hands of the police," she told Briarpatch. "We can't let this issue go. The statements by our unions need to be complimented by concrete action."

Now is the time to renew the call to remove police and all state security forces from the labour movement – but doing so will require a groundswell of pressure from below. In the United States, amid brave acts of solidarity with protestors by unionized bus drivers and dockworkers, the leadership of America’s largest federation of unions is resisting calls to expel police unions from their ranks. In Canada, police associations are not part of our central labour body, the CLC, but unions affiliated with the CLC have members involved in many aspects of policing and the prison industrial complex – from the RCMP to jail guards, and immigration enforcement agents to transit cops.

Union members deserve to have a say in the organizing priorities of their unions. Bold statements about our commitment to racial justice must be put into action. Cops out of CUPE provides a helpful starting point for this conversation with their call to revoke the charter of the RCMP local and discontinue organizing efforts with any civilian or non-civilian elements of state security forces.

“No amount of education is going to change the fundamental function of policing: to watch, control, and attack Black and Indigenous lives and other people undervalued in our society, including union members.”

On June 10, the Canadian Labour Congress hosted a webinar called “What Are Unions Doing About Anti-Black Racism?” The CLC representatives did not raise the topic of police unions or police in unions, but guest speaker Sandy Hudson, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto, called on unions with police in their memberships to rethink their approach. “If labour unions want to be in solidarity with Black people, they can’t be working with state security forces, which are constructed at their very core to be anti-Black,” she said.

Briarpatch asked Hudson for her thoughts on the argument that “it’s better to keep state security forces in our unions so we can educate them.”

“No amount of education is going to change the fundamental function of policing: to watch, control, and attack Black and Indigenous lives and other people undervalued in our society, including union members,” she said.

Indeed, the reason “teaching out” racism doesn’t work in police forces isn’t because we haven’t thrown enough time or money at the problem, it’s because anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism is a structural feature of policing in Canadian society. As Black Lives Matter activists have said time and time again: the system isn’t broken – it was built this way.

Why we must defund the police and police unions

Hudson also urged trade unionists to support the growing movement to defund the police, on which the CLC does not yet have a position. Making such a transformative shift in the allocation of social spending will obviously be met with resistance from some quarters, not least from police associations.

Police associations have an inordinate amount of power, and they wield it to help shield their members from accountability measures, to deny the existence of systemic racism, portray themselves as victims, and keep their political opponents in check. In Toronto, the police association has enough sway to influence who is chosen as police chief, spiking a more reform-minded candidate in the last hiring process.

The charge of “overpowered” unions is a familiar one, as it is often disingenuously levelled against real workers’ organizations. It is true that we can build power when we organize collectively – in fact, it is the only real power that we have – but workers fight asymmetrical battles against opponents with far greater wealth, and militarized police forces to back them up. Rather than fighting for the common good, police associations are narrowly focused on protecting their own ability to operate with impunity.

Every successful effort to redirect funding from the police reduces their ranks, and in turn, the resources of police associations.

It is not enough to simply denounce and maintain critical distance from police unions. In order to defend our communities we must challenge their base of power. In the United States, along with the call to expel police unions from the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), policy analysts have made the case for barring police associations from the right to collectively bargain. Others have called for limiting the scope of their bargaining to strictly wages and benefits.

The first problem with these approaches is that they aim to reform police associations when it is clear that the institution of policing cannot be fixed. The second issue is that they require getting the state to strengthen, rather than dismantle, existing constraints within its labour laws in order to protect us from their own security forces.

Instead, we might adopt the same direct approach advocated by the broader Movement for Black Lives: defund the police. Every successful effort to redirect funding from the police reduces their ranks, and in turn, the resources of police associations.

How we can prioritize life and decent work for all

To be clear, the call to defund the police is a radical demand, in the sense articulated by Angela Davis: “Radical simply means grasping things at the root.” Defunding is not a call to reform or scale down policing, which only authorizes further Black and Indigenous death at their hands, but to replace it with a completely different approach.

Well-meaning reformists in the labour movement argue that some members of state security forces are also marginalized and deserve representation, even though they are complicit in perpetuating harm, such as prison guards who are working-class people of colour. Yes, prison guards do face difficult working conditions, and prisoners feel the repercussions of this.

An abolitionist approach to “decent work for all” ensures that work is socially meaningful and life-affirming, rather than being contingent on suffering and premature death at home or abroad. The money for a just transition is already on the table, including $15 billion per year for policing in Canada. Right-wing governments have normalized the defunding of public services for decades while police budgets have ballooned. Unions shouldn’t be pushing to build new jails. We need to redirect our money from police, prisons, and pipelines to people and communities.

An abolitionist approach to “decent work for all” ensures that work is socially meaningful and life-affirming, rather than being contingent on suffering and premature death at home or abroad.

As Rinaldo Walcott writes, we can invest in “communities in distress, giving them access to better housing, health care and transportation, and ownership over how conflict is managed in their communities.” Correctional Service Canada is the largest employer of Indigenous people in the federal public service. Is that a win for employment equity or a tragic waste of human potential? Abolition is a framework that advances better futures for Black and Indigenous people than guarding jail cells or residing in them.

At its heart, trade unionism is an emancipatory working-class movement that is necessarily anti-racist, just as it is feminist, queer, anti-ableist, anti-colonial, anti-war, and anti-capitalist. We can’t justify our collusion with state security forces by uncritically parroting the slogan “all workers have the right to organize.” This blurring of lines depoliticizes what it means to be a worker.

Rather than drooling over employment growth within the prison industrial complex, our job is to end it. We must imagine, organize, and build alternatives in a spirit of abolition that will make our labour movement ancestors and descendants proud.

Say it with me: organize workers, not cops. Build communities, not prisons. Defund the police, invest in people.