In the summer of 2019, street evangelists descended upon a Pride festival in Hamilton, Ontario. Not content to jeer and heckle about damnation, white supremacists showed up with weapons and body armour along with their usual Jesus signs. Expecting their presence, community members erected a reinforced banner, shielding celebrants from the vitriol. Thwarted in their original plans, the preachers devolved into brute violence, but Pride defenders and nearby attendees who joined the fray held their ground. Meanwhile, police officers stood by watching, reminding a bystander, “Don’t you remember that we weren’t invited to Pride?” Despite injuries, the community emerged victorious, ultimately succeeding in driving off the attackers.

Though the Pride defenders unequivocally rejected calls for police intervention, the events sparked widespread outcry for state action against hate in Canada. Politicians, Pride organizers, and non-profit civic leaders denounced hate and violence, calling for arrests and new “zero-tolerance” policies to address the city’s standing as “the hate crime capital of Canada.” The police commissioned a $600,000 independent review that recommended the Hamilton Police Service expand the new role of their LGBTQ liaison officer. Nearly five years after the attack on Hamilton Pride, that officer sits as the festival’s official security coordinator.

The defenders’ undeniable triumph over reactionary violence at Hamilton Pride and the state’s subsequent instrumentalization of the “rise in hate” are instructive in the current moment. For queer, trans, and racialized people, fears of everyday violence from racists and queer-bashers are a constant backdrop to our lives. Simultaneously, politicians smear us and our comrades as hateful for taking action to halt Israel’s genocide of Palestinians, with police cracking down on protests and postering in the name of “zero tolerance for hate.” The state’s cynical use of hate investigations to repress dissent reveals the real function of “anti-hate” as a counter-insurgency strategy.

Repression against us

Amid an increase in anti-Palestinian and anti-Muslim racism, “anti-hate” infrastructure has mobilized to criminalize solidarity with Palestinians. In January 2024 alone, Toronto Police Service (TPS) laid at least four charges against Arab protesters in relation to hate investigations. TPS announced that one of these arrests was allegedly “for displaying [a] terrorist flag” – the flag of the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – an act they themselves have previously stated is legal. Instead, they charged the arrestee with the rarely-used offence of “public incitement of hatred.”

Following up a month later on a December 2023 incident where demonstrators say a Zionist instigated a confrontation with them in the Eaton Centre, the TPS Hate Crime Unit (HCU) pursued a search warrant against two alleged participants instead, accusing them of unlawful assembly and several other offences. Two days after the Eaton Centre arrests, the HCU executed another search warrant and charged someone with mischief. This was for their alleged connection to a blockade of the Gardiner Expressway in November 2023, which had lasted an entire four minutes.

The Calgary Police Service accused Palestinian organizer Wesam Khaled of a “hate-motivated” offence last November for chanting “from the river to the sea.” Public pressure, however, forced the Crown to stay the charge. HCUs investigated posters and paint at metro stations in Montreal and an Indigo bookstore and a Starbucks in Toronto. After early-morning house raids, the Peace 11, for their alleged participation in the action against Indigo, are facing conspiracy, mischief, and criminal harassment charges reminiscent of the G20 crackdown. Though none of the charges are for hate offences, mainstream reporting has widely disseminated TPS’s claims that the posters condemning Indigo CEO Heather Reisman’s support for the Israeli occupation forces were “hate-motivated.” Some media outlets and police have collaborated to turn the 11 arrestees, long-time community organizers now contending with professional consequences and harassment, into faces of “the rise of hate.”

Amidst an exponential surge in anti-Palestinian and anti-Muslim racism, “anti-hate” infrastructure has mobilized to criminalize Palestine solidarity.

The public smear campaign against Palestine solidarity relies in part on the fact that Canada’s hate laws are complex. There are few actual “hate crimes.” The Criminal Code has two categories of hate offences: “hate propaganda” and “mischief to religious property, educational institutions, etc.” Hate propaganda consists of “advocat[ing] or promot[ing] genocide,” “incit[ing] hatred against any identifiable group where such incitement is likely to lead to a breach of the peace,” and wilfully promoting “hatred against any identifiable group” or “antisemitism by condoning, denying or downplaying the Holocaust.”

If an accused person pleads or is found guilty of a criminal offence, a judge will decide their sentence. At this sentencing stage, hate motivation is the first of a long list of aggravating and mitigating circumstances. If the court finds that a person committed a crime motivated by “bias, prejudice or hate,” it hands down a more severe sentence. The Crown prosecutor may seek “hate-motivated” sentencing against an accused person. Officially, police have no say in this decision. Despite that, police statements sometimes refer to charges that do not allege hate offences as “hate-motivated,” referencing the possibility of sentencing enhancements.

Even if the law did not define “hate” so poorly, state repression against the left in Canada largely does not involve findings of guilt or jail sentences.

The Criminal Code defines an “identifiable group” as “any section of the public distinguished by colour, race, religion, national or ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or mental or physical disability.” It does not define “hate,” but the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R v Keegstra set out interpretive guidance for lower courts and law enforcement. R v Keegstra says that “‘hatred’ connotes emotion of an intense and extreme nature that is clearly associated with vilification and detestation” which, “if exercised against members of an identifiable group, implies that those individuals are to be despised, scorned, denied respect and made subject to ill treatment on the basis of group affiliation.” Conspicuously, nowhere in these definitions does power enter into the equation.

Neither hate offences nor “hate motivation” sentencing require actual oppression to be defined as such. HCUs across Ontario regularly report a small number of “anti-white” incidents. Moreover, courts have sentenced Black and Indigenous people for “hate-motivated” crimes against white people and Christianity.

But even if the law did not define “hate” so poorly, state repression against the left in Canada largely does not involve findings of guilt or jail sentences. Police have enormous discretion in conducting surveillance up until they lay charges, if they lay charges at all. The average person has no way of knowing what information the state has about them unless it ends up before them in a disclosure, a compilation of all potentially relevant evidence that the Crown must share with an accused person.

Hate crime units across the country routinely take on leading roles in criminalizing left movements, like in the Toronto G20 conspiracy case and even farther back.

The frequency and disproportionality of repression against the Palestine solidarity movement is unparalleled in recent memory, but police in Canada have been weaponizing “anti-hate” against the left long before Israel’s latest genocidal assault on Gaza in October 2023. In the fallout from Hamilton Pride in 2019, the first arrest was of a trans woman anarchist, Cedar Hopperton. Hopperton had not attended Pride; she spoke in support of queer self-defence at a public meeting afterward. For that, she spent nearly a month in jail. Court documents show that a plainclothes HCU member had taken detailed notes, the main basis for revoking her parole. Police would go on to arrest four more members of the LGBTQ community and one member of the anti-Pride contigent, as the defenders had warned would happen, the last of their charges dragging on into 2021.

Local HCUs have similarly targeted demonstrators supporting 2SLGBTQ+ communities in Calgary. In June 2023, the HCU investigated and charged Taylor McNallie and Adora Nwofor with assault and other “hate-motivated” offences over an altercation between the two Black women organizers and white anti-trans protesters. Officers had initially charged Nwofor with mischief to Catholic school property for reasons of racial hatred; the Crown later withdrew that charge, claiming it was a “clerical error.”

During #ShutDownCanada protests in 2020, a hate crime unit tracked Wet’suwet’en solidarity organizers in Southern Ontario.

Allegations of hate crimes victimizing the far right, while far from commonplace, cannot be dismissed as one-off flukes. In 2022, weeks after the end of the Freedom Convoy, Ottawa’s HCU investigated spray paint saying “fuck off fascists” as hate-motivated mischief against a pro-convoy church. Halton Police made international headlines in 2020 for launching a hate crime investigation after a Waffen-SS memorial was graffitied with “Nazi war monument.” While the police hastily apologized and retracted their initial statement, similar investigations by other police forces have received far less attention. Reports by Hamilton’s HCU from the late 2000s list “police” as a victimized group alongside identities such as “Jewish” and “Black.” One of their key recommendations for addressing “hate-bias incidents,” a category that included anti-police graffiti, was for the HCU to participate in graffiti prevention strategy by offering intelligence on anarchist groups.

Indeed, HCUs across the country routinely take on leading roles in criminalizing left movements, like in the Toronto G20 conspiracy case and even farther back. The public inquiry into the use of the Emergencies Act in 2022 inadvertently revealed the existence and origins of Project Hendon, a joint intelligence project sharing regular reports with municipal, provincial, and federal police agencies across Canada. While repurposed during the Ottawa convoy, the Ontario Provincial Police’s (OPP) Provincial Operations Intelligence Bureau (POIB), which includes its HCU within its anti-terrorism section, initially created the project in February 2020 to surveil the Tyendinaga solidarity rail blockade and 1492 Land Back Lane. Hendon’s case manager during the convoy, Brian Barclay, simultaneously managed the OPP’s anti-terrorism section and HCU.

An RCMP hate crime unit assisted in monitoring 2016 Black Lives Matter Vancouver protests; their internal communications were preoccupied with any anti-police sentiments from organizers.

During #ShutDownCanada protests in 2020, an HCU tracked Wet’suwet’en solidarity organizers in Southern Ontario. In response to chalk messages about free tuition and decolonizing education at McMaster University in 2019, special constables shared surveillance footage with the Hamilton Police Service’s HCU to ask for their assistance in identifying a suspect. A HCU within the RCMP assisted in monitoring 2016 Black Lives Matter Vancouver protests; their internal communications were again preoccupied with any anti-police sentiments from organizers. Older Hamilton HCU reports laid out investigative priorities that included, on top of the G20, opposition to the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, anarchist anti-police activity, and Indigenous land reclamation.

Some of the same players reappear in these various agencies and operations across decades. The head of the POIB and Project Hendon’s director since its inception, Patrick J. Morris, specializes in protest intelligence for the OPP’s HCU. His resume boasts of his involvement in policing the 2002 G8 summit in Kananaskis, the 2006 Kanonhstaton reclamation, the 2010 Vancouver Olympics protests, Idle No More, 1492 Land Back Lane, and the Tyendinaga rail blockade, as well as his handling of undercover operators. Tying it all together, Morris served as co-lead of the Primary Intelligence Investigative Team dedicated to monitoring and infiltrating the 2010 G8/G20 protests.

Reports by Hamilton’s hate crime unit from the late 2000s list “police” as a victimized group alongside identities such as “Jewish” and “Black.”

In addition to the criminal law (a federal matter), provinces and municipalities can pass their own laws about discrimination and hate. Some provincial human rights codes, under which people may obtain financial compensation and other orders to remedy discrimination in services and public life, include hate speech prohibitions. Hamilton bylaw enforcement ordered the removal of a circle-A sign (a symbol of anarchism) in 2018, calling it “hate material,” before the public embarrassed the city into walking it back. Municipal bylaws may also prohibit behaviour such as “hateful” harassment on city property under penalty of fines. In 2023, Calgary bylaw officers charged a teenager under an anti-street harassment bylaw for attending a counter-demonstration in support of trans-inclusive change room policies. After a public petition, the city declined to proceed with the charge.

In response to Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow’s motion “Keeping Toronto Safe from Hate” from October 11, 2023, the Toronto Police Services Board (TPSB) published a public letter about TPS and its HCU’s work on the issue. The letter revealed that the HCU has attended “all-related protests and demonstrations” since October 7 and is taking charge of every related investigation, regardless of whether a hate crime is suspected. Not only that, but Toronto’s HCU is a member of provincial and national hate crime teams that share intelligence and analytical support. The letter also confirms that, post-convoy, the focus of Project Hendon’s regular intelligence briefings and multi-agency calls has shifted onto Palestine solidarity. Under the pretext of a “response to hate crime,” TPS has reassigned significant resources from other operations to bolster the HCU’s capacity for surveillance.

Establishing anti-dissent infrastructure

In 1993, the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) established the country’s first dedicated HCU, 23 years after Parliament passed the country’s first hate propaganda provisions. Since then, similar specialized units or individual officers have cropped up in many more major cities. But hate prohibitions and designated police resources to enforce them have not always been popular. A time before hate laws remains within living memory in Canada. Many members of oppressed communities, seeking safety from real and pressing threats of violence, continue to advocate for more resources for HCUs, better training for investigators, and additional laws to fill perceived gaps.

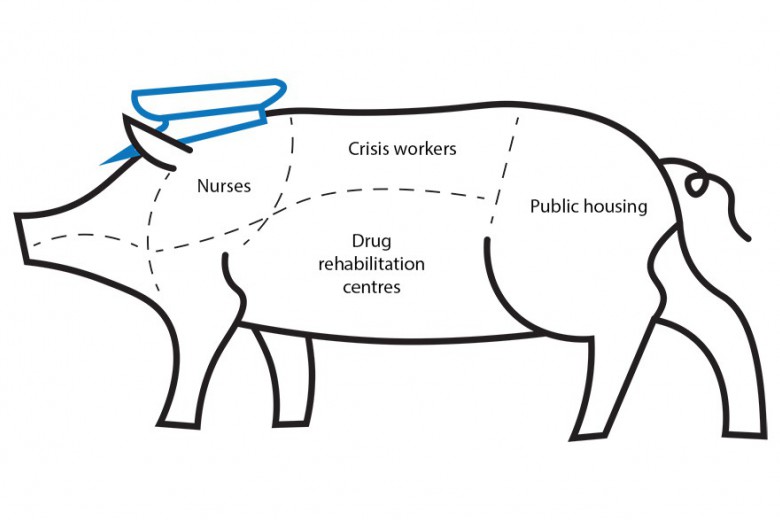

The problem with this is that non-abolitionist reforms only expand the state’s capacity for violence. Anti-hate projects are no exception. It is no coincidence that in the U.S., “Stop Asian Hate” gained institutional traction in the wake of the 2020 uprisings against anti-Black state violence. While the uprisings demanded an end to policing, the state instead embraced “Stop Asian Hate” for its compatibility with “anti-racist” tough-on-crime policy. The increase in racism against East Asians at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic coalesced with those communities’ often-unchallenged assimilationist politics to produce anti-Black hysteria with a progressive veneer. In San Francisco, reactionary Chinese Americans fear-mongered about an epidemic of Black-on-Asian crime, blaming and ultimately successfully removing prosecutor Chesa Boudin, elected on a platform of decarceration and police accountability, from his position.

Anti-hate is, therefore, both a counter-insurgent logic and the increasingly expansive state infrastructure that operationalizes it.

Echoes play out north of the border, as reactionary Chinese Canadians team up with politicians and NIMBY property owners to invoke their communities’ safety in support of the drug war. The campaign that elected Vancouver’s first Chinese-Canadian mayor, Ken Sim, centred on his love for the police and rhetorically pitted Chinatown residents against criminalized drug users. The framing of “hate,” which demands protection from the law, inherently precludes a holistic understanding of how the state itself produces white supremacist violence. That fatal flaw makes public indignation about the “rise of hate” into a convenient wedge against genuinely liberatory demands.

Anti-hate is, therefore, both a counter-insurgent logic and the increasingly expansive state infrastructure that operationalizes it. Hate crime response increasingly means provincial, national, and international coordination between different state agencies. In addition to naming Project Hendon, the Toronto Police Services Board letter announces the HCU’s participation in a National Hate Crime Working Group, details of which are sparse. It reveals that TPS is launching

a “Global Shield Initiative” in Toronto, a counter-terrorism intelligence-sharing network spanning law enforcement and private sector actors internationally. The inclusion of the latter brings to mind the RCMP’s Integrated Security Unit and Joint Intelligence Group’s enmeshing of private security into its “war room” during the Toronto G20, as well as the Community-Industry Response Group’s collusion with private security and resource extraction companies against Wet’suwet’en land defenders. Local HCUs are thus entangled with sprawling international surveillance apparatuses that the state, domestically, deploys primarily against oppressed communities and the left. All this gives away that anti-hate infrastructure does not actually exist to protect potential targets of reactionary violence from street-level harassment and assault, or even from far-right mass murderers.

Rather, the centrality of HCUs to political repression in Ontario underscores a core part of their purpose: targeting us. Police themselves admit it. The Hate Crime and Extremism Investigative Team (“HCEIT”) is a network of 18 Ontario police agencies that collaborate on their operations. It boasts of initiatives such as a “Right- and Left-Wing Extremism Seminar,” overviewing “left wing groups,” “right-wing groups,” “symbols,” “rhetoric,” and “recent local case examples.” The addition of “extremism,” a term that conflates Indigenous land defenders with white supremacist mass shooters, makes political repression an official part of HCEIT’s mandate.

Anti-hate infrastructure does not actually exist to protect potential targets of reactionary violence from street-level harassment and assault, or even from far-right mass murderers.

The Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police calls “hate” and “extremism” “close cousins;” police across the country often treat the concepts as interchangeable. Every year, TPS states outright that HCUs monitor “demonstrations with political or ideological overtones where the involved groups were strongly opposed to one another.” This rhetorical slippage reveals again how the logic of “hate” serves the state even without any hate crime charges or sentence enhancements. In other words, the Criminal Code is only a small part of the problem; the entire conceptual framework is a Trojan horse for carceral expansionism.

Though it was the first in Canada to pilot a specialized unit, the OPS unceremoniously disbanded its HCU in the mid-2010s – and then reintroduced it in 2020, immediately before the pandemic’s arrival. HCEIT has grown from five member agencies in 2003, to 13 in 2011, and 18 as of 2022. All this takes place within a larger trend toward streamlining policing and national security operations across jurisdictions. In support of Bill C-19 before the House of Commons, a budget bill that also added Holocaust denial to the Criminal Code, Liberal Member of Parliament Chandra Arya called for “a unified approach between all government departments to seamlessly share the information for a unified response” to threats such as “ideological extremism.” He suggested a new, comprehensive national security strategy wherein the RCMP, CSIS, and local law enforcement share their responsibilities with the armed forces, cryptologic agency, public health, and others. The left must unambiguously reject any notion that such proliferation of “anti-hate” policing is at all a victory for our communities.

Rejecting the logic of “hate”

As oppressed peoples, “hate” tells us that reactionary violence is about bad feelings. The individual perpetrator, full of ignorance and hate, acts it out against a helpless victim. Hate crime legislation, supposedly, enables the state to protect the victim and their community by locking away the perpetrator. The sentence, along with thoughts and prayers from politicians, sends the message that “hate has no home here.”

But our lives are not threatened by bad feelings alone; our enemies are structures of power and the genocidal state itself. The frame of “hate” deliberately obscures that Canada exists only through displacement and domination. After a viral rant where former high-ranking U.S. government official Stuart Seldowitz threatened an Egyptian food vendor with torture and deportation, Manhattan prosecutors pressed charges. But for every Seldowitz charged for terrorizing someone on the street, a thousand more continue to set foreign and domestic policy.

It is all the more urgent, then, to understand that “anti-hate” is counter-insurgency. Hate laws, hate crime units, and the very frame of “hate” itself are state ploys for our trust, promising protection in exchange for assimilation. But, though cliché, our liberation is bound up together. Our safety can only come from collective struggle against settler colonialism and white supremacy.