Étienne Belair remembers the disappointment he felt after police in Sept-Îles, Quebec, left him and his twin brother, Samuel, at the side of the road on an early morning in January. Samuel had begun showing signs of another psychotic episode earlier that night while they were at a chalet with friends, and they were driving back home when he ripped open the car door and jumped out. “I could tell he was losing grip with reality,” said Étienne. “I was driving at 40 to 50 kilometres per hour.”

After Samuel headed off into the forest without a jacket on, Étienne reached to call 911 in the hope someone could bring his brother to a psychiatric ward. Police found Samuel a short distance away, hitchhiking, but refused to transport him to hospital, saying they didn’t believe he was a danger to himself or others.

“I wish police would have interned me or at least forced me to take a trip to the hospital to get psychologically evaluated. All they did was call a social worker and then they let me go back home in a full psychosis,” says Samuel Belair. He remained in a psychosis for weeks after the incident, which led to police getting called in again – something he believes might have been prevented if he had received rapid treatment that night.

At least 10 people in Canada have died this year after being shot or tasered by police as a result of police being summoned for a mental health-related call.

This sense of frustration with how police handle distress calls is common among those living with mental illnesses and their families as well as among those who provide services for the houseless and those coping with drug addiction.

In 2014 – the last year for which data is available – 256,000 Canadians reported that they had come into contact with police in the last year because of problems with their emotions, mental health, or alcohol or drug use. The end result can be fatal. At least 10 people in Canada have died this year after being shot or tasered by police as a result of police being summoned for a mental health-related call.

Calls to remove police from situations involving people in distress have been growing louder ever since a slew of deaths involving police responding to mental health calls rocked the Greater Toronto Area over April and June. Twenty-nine-year-old Regis Korchinski-Paquet fell to her death from her high-rise balcony after Toronto police were called to bring her to a psychiatric hospital, while 26-year-old D’Andre Campbell, of Brampton, and 62-year-old Ejaz Choudry, of Mississauga, were fatally shot by Peel police at their homes.

Police interventions in Canada have led to the deaths of 555 people since 2000, a recent CBC investigation found, and 2020 is looking like it could be the deadliest year on record so far, with 30 deaths already counted in the first half of the year. The majority of the deaths this year resulted from police responding to mental health-related calls or drug use, and Black and Indigenous people are overrepresented among those killed.

“They make the situation worse”

That violence will continue as long as police continue to be the first on scene in situations involving those in crisis, says Rachel Bromberg, who’s worked at crisis support phone lines for the past several years and provides de-escalation training at Toronto’s largest psychiatric hospital, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). The way police operate will always be at odds with what people in distress need.

She wants to see crisis workers with de-escalation training take on this work instead.

“What’s really important with the mobile crisis team is to have a lot of time to really be patient with someone, really hear their story, figure out what they need, and figure out how you can help them. Whereas with police it’s all about clearing the call as soon as possible,” she says. Their next priority is determining whether there’s been a crime, Bromberg explains; providing police with additional training or allowing a mental health professional to stand by won’t change that.

“That’s how they deal with people. There’s no talking to them – they tie you up and throw you in a car,” he says. “They make the situation worse.”

Provincial mental health acts in Canada also restrict the viability of dispatching crisis workers as an alternate to police. At present, only police have the authority to transport someone to hospital if they’re unwilling to go voluntarily, and provincial legislation would need to be adjusted to allow crisis teams to restrain people and bring them to the hospital involuntarily. A psychiatrist or physician can only force an involuntary stay once someone has already arrived at the hospital.

“I think what they [people in crisis] really need is a sit-down therapy session,” Étienne told Briarpatch.

Charlie Williams feels the same. He’s called 911 several times over suicidal thoughts and drug-induced psychosis, and he says he’s been handcuffed each time he’s dealt with police. “That’s how they deal with people. There’s no talking to them – they tie you up and throw you in a car,” he says. “They make the situation worse.”

“No one in the hospital ever offered me rehab, no one offered any way to get off drugs. They just tied me down to a bed, gave me liquids, sobered me up, and kicked me out of the hospital in the morning.”

A fourth emergency service

After gathering like-minded people and co-founding the Reach Out Response Network this June, Bromberg has been in talks with the City of Toronto in the hopes the city will contract them for a new emergency service. Her hope is that it would remove police from the majority of mental health-related calls.

On June 29, the city council agreed they would begin researching the implementation of an emergency service based on the CAHOOTS model out of Eugene, Oregon.

CAHOOTS, or Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets, has been operating in Eugene since 1989 and has since been expanded to Springfield. Every 911 call relating to addiction, disorientation, a mental health crisis, or houselessness is automatically routed to them unless the dispatcher believes the person may pose a serious danger to first responders. Teams are typically composed of medical staff and mental health professionals, and each is required to undergo 500 hours of de-escalation and crisis intervention training.

A 2019 report issued by CAHOOTS found first responders tended to 24,000 calls, around 17 per cent of all 911 calls that year. Police were called in as backup only 250 times.

Toronto police have had the option to call in a mental health nurse from surrounding hospitals whenever they’re dealing with a mental health-related call since 2014, but the program has seen limited success, says Mike Colle, one of the Toronto city councillors pushing for the creation of the new crisis service.

“The problem is it’s under the control of the police,” he says. Police aren’t removed from the interaction, and whether or not a nurse is called is ultimately at their discretion. Records show that nurses are rarely called in – and only after police have already arrived, he says. The service doesn’t run 24/7, either.

CAMH has since called for police to be removed from interactions involving people in distress, calling it a public health concern, not a criminal one.

Between July 2014 and March 2015, Toronto police received 23,568 calls involving “emotionally disturbed persons,” according to a report evaluating the program soon after its implementation. Only 4,314 – less than one fifth – resulted in police involving mental health professionals.

Similar collaborations with hospitals have also been introduced in police services in Halifax, Edmonton, Calgary, and several regions in Ontario.

Those surveyed about their experience with the service in Toronto said they were often handcuffed and felt criminalized throughout their encounters with police, says Vicky Stergiopoulos, one of the researchers behind the report and the physician-in-chief at CAMH. “Many of them may feel increasingly agitated and paranoid when seeing individuals in a police uniform,” she told Briarpatch. Throughout the period studied, nurses never handcuffed those in distress.

CAMH has since called for police to be removed from interactions involving people in distress, calling it a public health concern, not a criminal one.

Beyond police and prisons

Some see the implementation of crisis workers as the first step toward the larger goal of abolishing police and prisons. Situations that involve sexual or domestic violence, the houseless, or drug use are some of the more obvious examples of areas where police should be removed, says Nathalie Batraville, an assistant professor at Concordia University and an organizer behind the call to defund the Montreal police budget by 50 per cent.

“There really is no situation that necessarily requires the police, and in fact the work of the police is so much at odds with the protection, the support, and the prevention of violence and harm,” Batraville said.

Defunding and ultimately abolishing police departments doesn’t yet have wide support among the public, but recent events in Minneapolis show that when reform is clearly no longer an option, abolition is put on the table. In early June, after weeks of protest and riots following the killing of George Floyd, nine out of 13 city councillors agreed to dismantle the police service.

“There really is no situation that necessarily requires the police, and in fact the work of the police is so much at odds with the protection, the support, and the prevention of violence and harm."

Simon Ash-Moccasin vocally agrees with such measures, particularly after the Saskatchewan Public Complaints Commission ruled that excessive force was used against him by Regina police during a violent detainment in 2014. The 2016 ruling and subsequent mediation facilitated by the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission resulted in police getting additional training on Indigenous history, including the impact of residential schools, and on the calls to action issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. While Ash-Moccasin appreciated the opportunity to go through mediation with the department, those reforms haven’t changed the reality of police violence and racial profiling for Indigenous people living in the city.

“They’ll use the example of what they did well with my case, and they’ll present that to the community,” says Ash-Moccasin, who’s from the Saulteaux First Nation. “Since that time, I don’t see much coming from it nowadays. ... We’re back at it again.”

Police services and the RCMP were created with the goal of controlling and criminalizing Indigenous people and other racialized communities, and it’s hard to see how these forces could overcome that history, he says.

The RCMP was originally founded as a paramilitary force in 1873 and named the North-West Mounted Police. In 1885, it joined the Canadian military in quashing the uprising of the Métis people led by Louis Riel as well as the Cree and Assiniboine in what would later become Saskatchewan. The force was instrumental in moving Indigenous Nations onto reserves to facilitate the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and in removing Indigenous children from their homes so they could be placed in residential schools. The RCMP also intervened in the 1969 Akwesasne border crossing dispute near Cornwall, Ontario, the Blood Tribe’s 1980 blockade along the band’s Cardston border in Alberta, the 1990 Kanesatake Resistance in Quebec, and the Wet’suwet’en resistance to the building of the Coastal GasLink pipeline this year – all faceoffs stemming from disputes over land.

“The RCMP was created as a paramilitary force, and that is why it still functions like one today,” says Sean Carleton, a historian at the University of Manitoba.

“Once people see what’s happening now and can connect it back to this long pattern going over a hundred years of anti-Indigenous actions, it seems clear that the force is not playing a role in facilitating nation-to-nation relationships,” he says. “If it’s not fulfilling that role, perhaps it has outlived its reason for existence.”

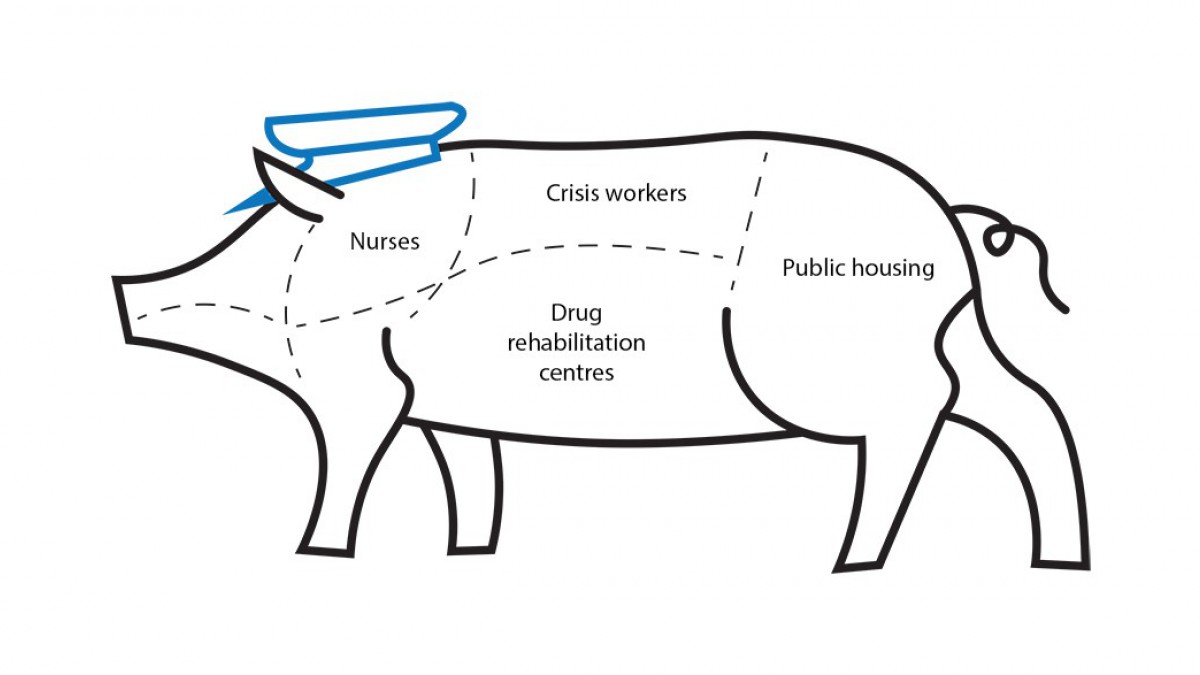

Using funds earmarked for police services and the RCMP to finance mental health resources, affordable housing, drug rehabilitation centres, and counselling for domestic violence victims would reduce the occurrence of mental health crises and crime as well, Batraville says.

“The RCMP was created as a paramilitary force, and that is why it still functions like one today.”

Colle envisions an emergency service in Toronto that could respond to much more than just mental health-related calls. First responders could work with the houseless, provide medical aid to someone who’s overdosed, respond to noise complaints, resolve disputes between neighbours, or respond to domestic violence. Ideally, police would only be called if someone in distress was carrying a weapon. Situations involving violent individuals without weapons could still be de-escalated by first responders with the appropriate training, he said.

Street workers told Briarpatch that it’s been especially challenging to get police out of distress calls involving people who are houseless. In his work as a palliative care doctor for people living on the street in Toronto and throughout Peel Region, Naheed Dosani has found it’s nearly impossible to avoid getting police involved whenever he has to call an ambulance. As a result, he says, Indigenous and Black people and those with disabilities face a disproportionate amount of violence from police.

“I do everything I can in my clinical care to not involve police,” says Dosani, who’s among a group of physicians in the city who serve Black and Indigenous people that is calling to defund the Toronto police.

Jessica Quijano, a project coordinator with the Native Women’s Shelter in Montreal, has encountered the same trend. At Cabot Square, a gathering place for First Nations and Inuit people in the city, the shelter employs outreach workers who work to de-escalate conflicts before they attract the attention of police. “There’s no reason that we would need police to do that kind of work, to be armed,” she says. “We need to stop treating people who are having mental health problems or addiction issues as criminals, and [we need to] look at it more from a public health [perspective] and actually provide them with the necessary help that they would need.”

“I put my number as a tip line when we’re trying to locate an Indigenous woman or girl, and I actually have been successful in locating people.”

When it comes to situations involving domestic or sexual violence, Quijano says the women she works with are looking for counselling that’s culturally informed – not justice meted out by the courts. Their partner could also be looking for help managing their anger or accessing a rehabilitation centre, but there are long wait lists for those who can’t afford to pay out of pocket. Men in poverty who are reeling from the impacts of intergenerational trauma are getting criminalized as a result, she said.

Missing persons also take up a large portion of the work police do, but these cases don’t necessarily require law enforcement to get involved, Quijano says.

“I put my number as a tip line when we’re trying to locate an Indigenous woman or girl, and I actually have been successful in locating people,” says Quijano, who works with families searching for missing Indigenous women and girls by supporting them in filing a police report. “A lot of it is calling people, calling resources, interrogating people. The whole idea of having an armed person come and do this when you’re trying to locate a missing person, or a victim of assault, it just doesn’t really make any sense.”

As the City of Toronto explores the possibility of a fourth emergency service, Dosani says he hopes to see emergency services run by and for the community. Health care is wrought with systemic racism, he says, and municipal services have the potential to perpetuate the same kind of violence. “Any tangible solution needs to be centred in the voices of people who are Black and Indigenous and people of colour, in our communities,” he says.

There’s no use implementing a new emergency service if municipal employees are going to replicate the police approach to social issues. Bromberg wouldn’t want to see a service that criminalizes houseless people over things like loitering or drug use, for example. Workers should also be from the communities they serve and speak the languages of those within them. Her network has been running consultations with Black, Indigenous, queer, and trans communities in Toronto, as well as with service providers who work with the houseless, so that they can avoid “giving a new face” to the same oppressive structures.

Update, November 3: This article originally stated that Jessica Quijano is a streetworker, when in fact she is a project manager with the Native Women’s Shelter's Iskweu project.