Common sense says that if you want to get somewhere you should know at least two things: where it is you want to go and where you are to begin with. It’s also helpful to clarify who’s coming along and who’s planning to stop you.

For a lot of people, when it comes to the labour movement, the obvious answer to the question Who are we? is unions; the destination is dignity and security (mainly for union members); and the starting place is a bit like a fluorescent-lit bunker with a public relations budget (unions are under attack and public opinion matters).

If this picture is even roughly accurate, it means that in practice (if not rhetoric) the labour movement excludes a lot of people. It excludes the majority of paid workers (who aren’t unionized) and all unpaid caregivers along with the unemployed. It means the labour movement is a defensive formation trying to hold ground in difficult times, rather than one going out into the world with a vision to change it.

Serious thinking often means holding contradictory ideas in your mind at the same time. In this case, it means recognizing that unions remain our single best defence for hard-won workplace rights and social programs that benefit everyone, while, at the same time, recognizing that unions are still invested in a social and economic arrangement called the postwar settlement that disintegrated more than thirty years ago, and that’s a problem for everyone.

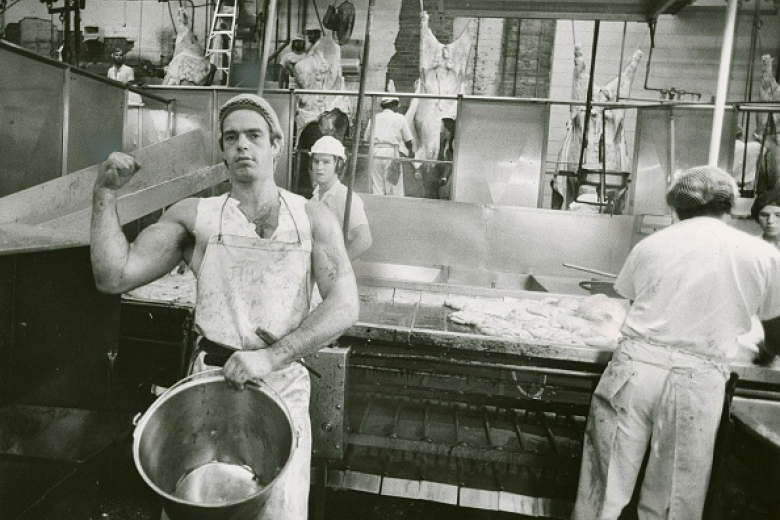

In the postwar settlement of the ’50s and ’60s, the labour movement’s broad acceptance of capitalism coincided with rising wages and improved working conditions, benefits, and social programs, all of which hinged on supercharged economic growth (coupled with courageous rank-and-file militancy). These gains always aided some people more than others, but it’s fair to say that most of the domestic working class benefited from the power of organized labour during this period.

Today, unions appear removed from – and at times even opposed to – social movements that seek systemic change, particularly when it comes to the environment, to the fate of young people, and to Indigenous sovereignty and land rights in Canada. And for this reason, many activists and organizers who work on these issues don’t appreciate how vital organized labour is if large-scale projects of social and environmental justice are to become reality.

After a national employment summit in Toronto in early October, the president of Canada’s largest private-sector union, representing more than 300,000 workers, praised the East Coast robber baron and mega-capitalist Jim Irving, whose family dynasty oversees the province of New Brunswick like a medieval fiefdom. “This is a family that knows how to create jobs, they know how to create wealth,” said Unifor’s president.

Tough luck, then, for trade unionists seeking to align themselves with the Mi’kmaq Warriors Society of Elsipogtog and their courageous opposition to fracking on unceded Mi’kmaq territories. And tough luck too, it seems, for anyone who thought the purpose of unions was to build working-class power, not to cozy up to billionaires (Jim Irving is among the five wealthiest people in all of Canada and one of the richest people in the world).

It doesn’t have to be this way. But for things to change, it will take much more than pointing fingers at people. It will require the patient and frequently frustrating day-to-day work of building a political left that has one foot inside the labour movement and one foot outside of it. Rank-and-file unionists need to encourage the militancy of fellow members, while also engaging with feminists, queer activists, Indigenous land defenders, anti-capitalists, and community organizers of all kinds in order to access voices and stories, struggles and analyses, that don’t flourish inside the labour movement. At the same time, activists outside the official labour movement must recognize that a left that’s disconnected from organized labour no longer has access to the human lynchpin of the capitalist machine. A left without militant organized labour is a left that is all protest with no real leverage.

The radical left in Canada is small, fractured, and starved of resources (after 41 years, this publication struggles to pay its monthly bills, with a staff of two). The labour movement has great capacity and resources but its base is demobilized and lacks ambition. Indigenous struggles are beautifully resurgent but also caught up in the everydayness of generations of genocidal oppression. Each of these divergent forces – the radical left, Indigenous struggles, and rank-and-file militancy – needs the others in order to flourish, but real solidarity won’t be built with slogans or pamphlets but instead with person-to-person relationships that require time and personal initiative to establish.

If we want to escape the gilded thumb of colonial billionaires like Jim Irving, it’s up to us, not our leaders.