In an effort to keep its workers from unionizing, Honda management meets biweekly to monitor unions and its internal ‘weaknesses’ – work area by work area and shift by shift – audio obtained by Briarpatch finds.

In audio from an anti-union conference, Honda Canada “advanced technical staff” head John Moulding is heard explaining how the company’s top managers meet regularly to monitor external union activity and map internal “work areas” vulnerable to union organizing.

“We always consider ourselves in campaign mode. The second you’re not paying attention they’ll come back with something,” Moulding told the conference, in a presentation titled 4,300 Associates Union Free at Honda in Ontario – How Does That Happen Over 30+ Years?

“Honda’s surveillance is more sophisticated than we’d typically see in a Canadian workplace and is part of a comprehensive union-avoidance program.”

Honda, which manufactures automobiles and power tools, has 31 companies across North America. At the Alliston, Ontario facility – which has two main car plants, an engine plant, and roughly 4,200 workers – Moulding noted all workers are provided with a copy of Honda’s Position On Unionization in their associate handbooks. It reads:

"A union can promise anything, but the only thing they can guarantee is that you will have to pay union dues which is currently 3 hours of pay per month (1.35% of regular gross monthly earnings). During working hours, no one has the right to solicit you to sign or not to sign a union membership card."

Moulding told the conference Honda developed its most recent “labour relations strategy” to be “more overt” in its opposition to unions because of a recent rise in new hires without much knowledge of “Honda and its history.”

When Honda first announced plans to build the Allison plant in 1984 – the first Canadian plant operated by a Japan-based car company – it was a non-union rival to the existing unionized North America-based companies.

“Since 1990, HCM [Honda of Canada Manufacturing] has been a target for various unions,” Moulding’s slideshow points out – including a timeline of unionization efforts by the Canadian Auto Workers in the 1990s and from 2007 to 2013; United Auto Workers from 2003 to 2007; and United Steelworkers in 2007. In 2017, Unifor began an internal union drive, which, according to Moulding, Honda’s system helped crush.

“We always consider ourselves in campaign mode. The second you’re not paying attention they’ll come back with something.”

Additionally, Moulding explained, Honda uses two main committees to monitor potential organizing activity.

Honda’s “associate relations committee” is the first. Moulding described it as a combination of managers and a “sounding board” of elected workers. The committee, he said, meets quarterly to review workplace policy. “Like a quasi-union,” he said, except “they don’t negotiate salaries or benefits and they don’t participate in discipline or terminations.”

In Britain, Honda UK faced allegations of union-busting after a Unite shop steward was suspended, according to the union, after printing off internal company documents encouraging one plant’s management to "minimise influence of trade union" and "accelerate independence of ARC [Associate Representative Council]." The Guardian reported that the ARC, an elected council Honda uses for pay bargaining, was dominated by representatives from the union.

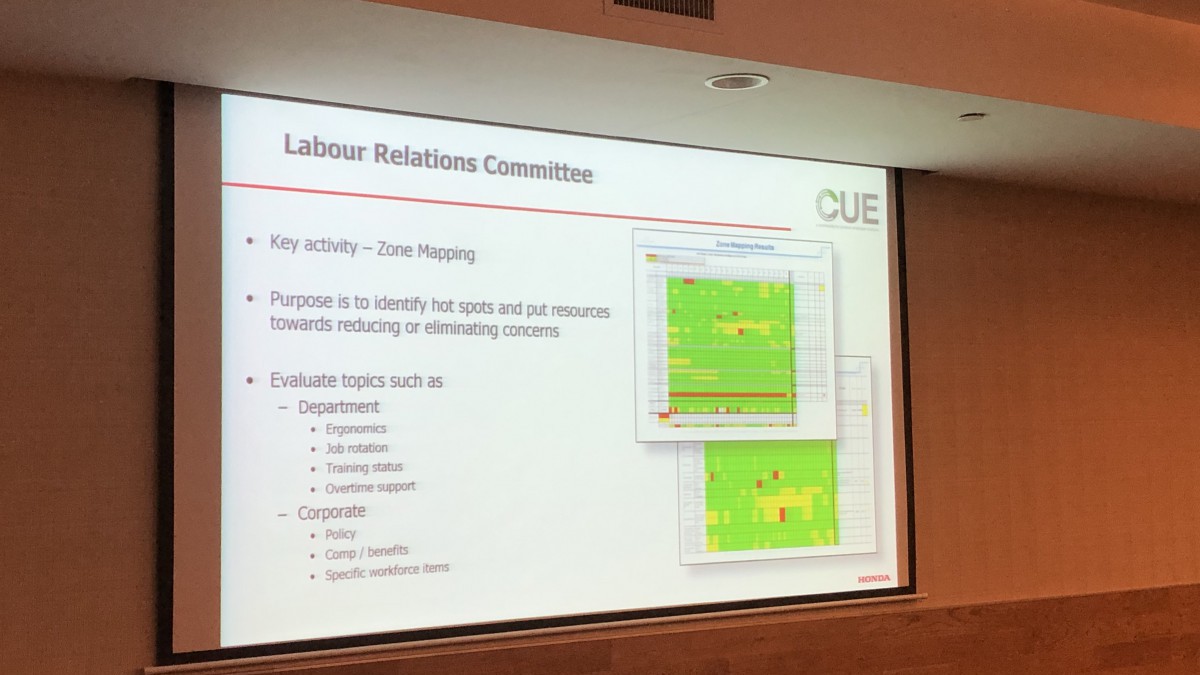

The second is Honda’s “labour relations committee,” made up of only management members from all departments “with a connection to the floor,” its slideshow reads. Those committee members, it said, are tasked with tracking “current and emerging issues” and “Identify[ing] other ‘mosquitos.’”

Moulding told the conference Honda developed its most recent “labour relations strategy” to be “more overt” in its opposition to unions because of a recent rise in new hires without much knowledge of “Honda and its history.”

For one, Moulding said, all of Honda’s managers are sent to “Positive Management Leadership (PML) Training” lessons overseen by PML President Terry Dunn. “We send all our leaders to his training,” Moulding told the conference.

The PML website includes resources on “vulnerability tests” and advertises “rapid response team training,” including how to “detect early warning signs” and “How to shut off card-signing, quickly.” According to his bio, Dunn personally led “crisis management teams for maintaining union-free operations” in Canada and the U.S. – including decertification drives, which terminate a union’s right to represent workers.

Honda is listed as one of PML’s clients on its website. And one of PML’s consultants, Bart Rovins, lists in his bio that he “spent 12 years with the Honda of America Manufacturing supply-base, where he served in a rapid succession of roles for one of Honda’s key Tier-1 suppliers, leading the plant and its associates through a plant start-up and consecutive expansions.”

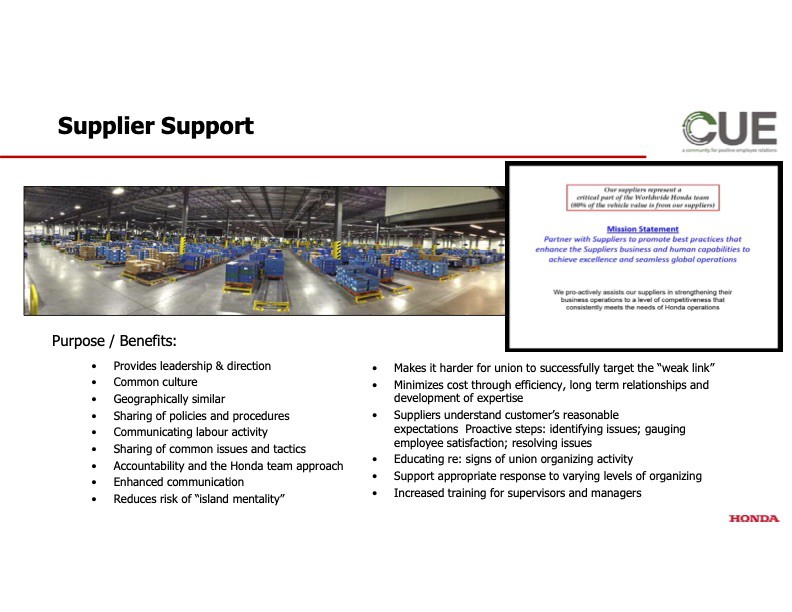

Dunn also serves on the Consultant Advisory Council of CUE, INC., which also had its logo featured on all of Honda’s conference presentation slides. Both Dunn and representatives of Honda North America are scheduled speakers at CUE INC’s upcoming Fall 2020 online conference – alongside speakers from AFIMAC, Inc., National Right to Work Committee, Sherrard Kuzz LLP, and the Labor Relations Institute, among others.

“If Honda is using CUE that is a sign to the unions and workers that they will fight hard against labour."

Harvard economics professor Richard B. Freeman told Briarpatch, “CUE is one of several employer groups that are strongly anti-union. They were formed to fight unions by NAM [the National Association of Manufacturers, a U.S.-based lobby group] and continue in that vein.”

“If Honda is using CUE that is a sign to the unions and workers that they will fight hard against labour,” Freeman added.

CUE did not respond to requests for comment, and PML declined to be interviewed.

The labour relations committee, Moulding said, monitors potential “hot spots” or vulnerabilities to potential organizing and makes sure “action” is taken.

Moulding said a key LRC task is conducting annual “zone maps” of complaints managers have heard, “by respective departments, by each work area, by each shift” and plotting them along a workplace map.

“We gauge the sentiment of our workplace. We will map that sentiment out based on a physical map of our workplace, at the department and plant level, so we get a better sense of the hotspots,” he said.

Moulding included an example of a “zone map” where the red, as he recalled, represented “burnout” across a number of shifts and departments. Once “hot spots” are identified, Moulding said, the company’s HR leadership uses it to inform its surveys of local union activity.

Moulding told the conference: “Some of this activity is proactive, too – we follow the cycle of our union activity. And for us, we follow the D3 cycle. Every time there’s a negotiation with the D3 in Ontario we know there’s going to be a campaign, in the next couple of weeks. So just before that we start talking about what we need to do from a labour relations standpoint.”

“D3” stands for “Detroit 3,” referring to the three biggest North American car companies: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler.

Stores like Whole Foods, owned by Amazon, use similar “heat maps” to track stores at risk of unionization. Business Insider reported that Whole Foods’ heat maps track “external risks” (like a high local unemployment rate and a short distance in miles between the store and the closest union); “store risks” (including low racial and ethnic diversity and low employee compensation); and “team member sentiment” (data from internal employee surveys about the quality and safety of their work environment)

Once “hot spots” are identified, Moulding said, the company’s HR leadership uses it to inform its surveys of local union activity.

“We all know we’re not immune,” Moulding said, “You’ve got to be prepared. What are the issues? And, maybe they’re issues that are standard and the unions have thrown them at every employer in the area – or maybe there are deep issues facing only some of the employers. What is the approach that the unions are taking? Are they overt? Are they covert? Are they online? Social media leveraging? What steps are they taking to try to organize?”

Athabasca University labour relations professor Bob Barneston told Briarpatch, “Honda’s surveillance is more sophisticated than we’d typically see in a Canadian workplace and is part of a comprehensive union-avoidance program.”

“By tracking and addressing worker concerns, the employer can reduce support for unionization. The monitoring itself can also put a chill on an organizing drive. Workers know the employer is surveilling and may fear retaliation for exercising their rights. This makes workers less likely to support the union,” he added.

Honda, Moulding added, works with other employers – chiefly its suppliers – to help monitor union organizing. “The ability that you have to leverage your network is really priceless,” Moulding said. According to the slide show, that can mean sharing best practices on workplace policies and union avoidance tactics.

The slideshow also encourages managers to “physically prepare your site.” Moulding explained, “We’ve also got a corporate security staff so it was important for us to bring them into the fold, particularly when we get site visits [from union organizers], so they know where the property lines are, where they need to push union people to without pushing them onto the road and creating a safety issue.”

Honda’s system, Moulding said, helped the company run a campaign to fight an internal union drive by Unifor starting in Fall 2017.

Unifor organizer Danny McBride told Briarpatch, “We’ve had a core of supporters there [at the Alliston Honda plant] for many years and we were getting calls from people after the D3 bargaining had concluded, that they wanted to see us back there and wanted to work toward getting unionized.”

In addition to typical leafleting at the plant’s periphery, he said, the workers spent time leafleting internally. “You don’t have a right to organize during working time such that it impacts your work. You can’t be organizing people down the line when you’re supposed to be working – you can be written up. But we don’t tell people ‘don’t talk about the union in the workplace,’” he explained.

“Most organizing drives are about fairness as a key principle and a voice in the workplace. Fairness is being able to negotiate instead of being dictated to the terms and conditions of employment.”

The workers inside the plant took the initiative to go to work early and remain after their shifts with leaflets. Those leaflets, McBride said, noted a collective agreement would give the workers a say in their workplace. That might provide, among other things, fairness for non-permanent workers and pension security.

“Most organizing drives are about fairness as a key principle and a voice in the workplace,” he said. “Fairness is being able to negotiate instead of being dictated to the terms and conditions of employment.”

And management noticed.

Moulding told the conference the internal leafleting was unlike what the company had observed before. “We’d find maybe a card on the table or a few copies of Unifor FAQs on the table but never very organized. But in 2017 that changed. One day we had four internal organizers per associate entrance, in their associate uniforms holding small white envelopes, as associates were coming in for their shift or leaving their shift.”

“That was pretty alarming for us,” he said.

Immediately, he said, management “took the opportunity” to remind workers of its “internal soliciting policy.” The company also monitored the union’s social media and web activity, he said, and prepared counter-messaging.

Eventually, Moulding said, the company observed internal leafleting activity decrease. “Over time, from early 2017 to June 2018, the support for the internal organizers dropped off significantly and we went from four internal organizer per associate entrance to two internal organizers in the month leading up to June,” he said.

“The last leaflet that was distributed was June 2018,” his slideshow notes.

Two years after organizing began, Unifor closed its office in Alliston in Fall 2019. While pro-union workers remain at Honda, the union decided there weren’t enough of them to maintain an organizing drive. “We concluded the workers are not ready to unionize yet. We’re ready when they are, but we have to respect their wishes,” McBride said.

That appears to have emboldened Honda management’s strategy.