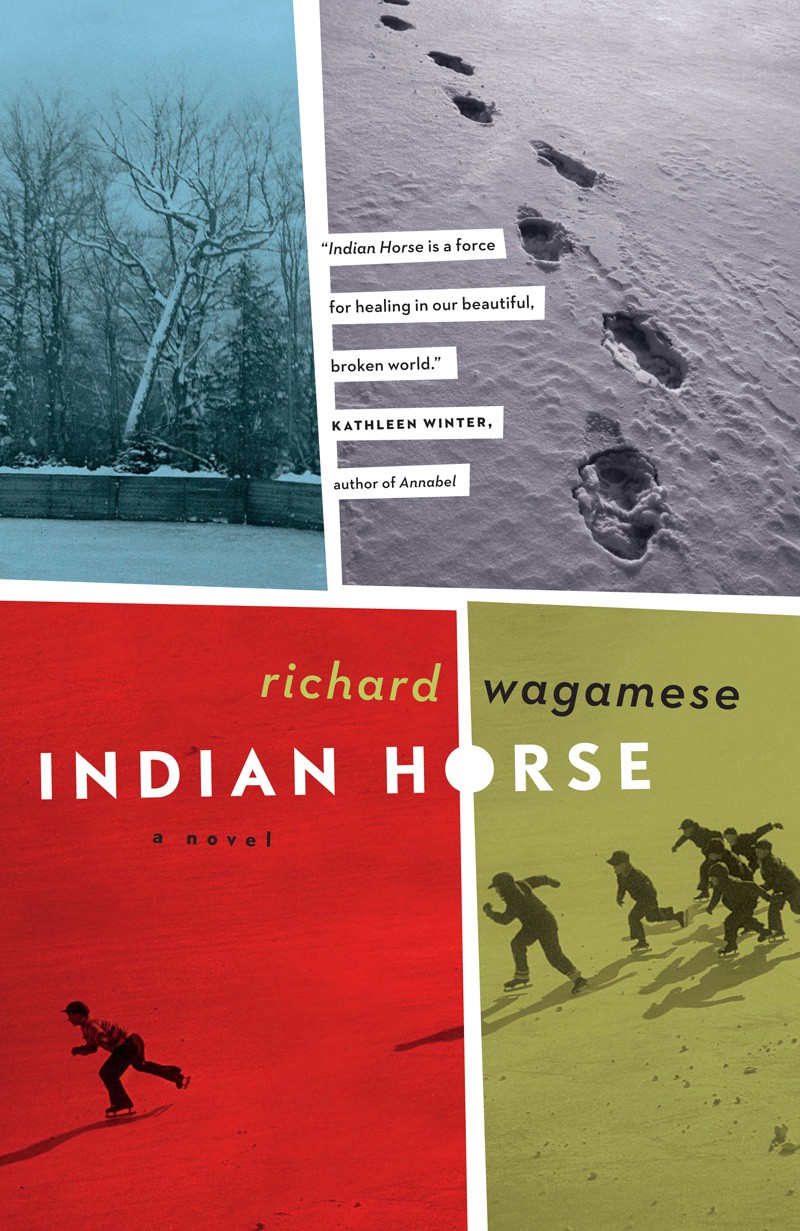

Indian Horse

By Richard Wagamese

Douglas & McIntyre, 2012

Ojibway author Richard Wagamese’s11th book opens in an addictions treatment facility in rural Manitoba. Saul Indian Horse is recovering after nearly dying on the streets of Winnipeg. As he heals, he reaches into his past to uncover the forces and events that brought him to the edge of oblivion.

Saul’s story is moulded by the horror of Canada’s residential school system. His parents, survivors of the schools, bear “a sorrow that could not be reached.” To protect her family from being taken from her again, Saul’s grandmother moves the family deep into the northern Ontario bush, hoping that a traditional Ojibway life will help them heal. But the arms of the Zhaunagush – the white colonizers – are powerful and far reaching, and soon Saul’s sister Rachel is kidnapped from them, never to return.

Saul is four when his brother Benjamin is also stolen from the family and is taken to a residential school. His parents drown their sorrow in drink, returning from town with the “white man in brown bottles.” Months later, Benjamin returns to the family after escaping from the school. On the urging of Saul’s grandmother, the family flees further into the bush to the sanctuary of God’s Lake. But Ben has returned both emotionally and physically defeated. When tragedy strikes the Indian Horse family breaks apart, and at eight years old, Saul is taken to St. Jerome’s Indian Residential School.

Beginning in the 1870s and up until 1996, over 150,000 Aboriginal children were placed in government-funded, church-run residential schools in Canada. The schools were a colonial project, developed to destroy Aboriginal culture by eliminating family and community involvement in the intellectual, cultural and spiritual development of Native children. Wagamese, a second-generation residential school survivor, paints a haunting picture of life in the schools, where Aboriginal culture is violently repressed and physical, psychological, and sexual abuse at the hands of nuns and priests is rampant. Children who died at the schools were buried in “row on row of four- and five-foot indentations like a finger from Heaven had pressed them down. Dips in the earth. Holes they fell into.”

Saul finds a respite from the pain when a young, idealistic priest arrives at the school and introduces the boys to ice hockey. Too young to play but enraptured by the game, Saul volunteers to clean the ice of the outdoor rink every morning. At night, under a framed picture of Jesus, he mimics the stick handling of the NHL players he has seen on the priest’s television set. He knows that his salvation will not come through religion, but will come “instead through wood and rubber and ice and the dream of a game.” When he is eventually given the chance to play, Saul’s passion for hockey is equalled by an almost magical gift for the sport.

Saul’s ability to understand the game, to see the puck, soon takes him outside the confines of St. Jerome’s. He leaves the school and is adopted into the family of the coach of a native hockey team in Manitouwadge. It is here, playing among peers in Native communities across northern Ontario, that his gift flourishes. We feel Saul’s racing heart as he discovers the soaring joy and camaraderie of the game. But when Saul is given the chance of a lifetime – a spot on a feeder team for the Toronto Maple Leafs – racism and the half-buried trauma of his experience in residential school begin to pull him under. The game that was a refuge turns toxic, and Saul flees, numbing the pain with alcohol.

Wagamese tells Saul’s story with sparse, effective prose. The novel reads quickly, never bogged down despite the weight of the subject matter. This works well with the personal reportage form Wagamese has chosen, but some key periods of Saul’s journey move too quickly. The book would have benefited from a closer exploration of Saul’s brief foray as the only Native youth on the town hockey team, and of his friendship with a grieving widower when he is an adult.

Indian Horse illuminates Canada’s devastating past in an important contribution to the genre of sport fiction. While the era of residential schools in Canada has ended, the harm of colonization has not; as Gitksan scholar and head of First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, Cindy Blackstock, notes, Native children continue to be taken from their families and placed in child welfare in numbers even greater than during the years of residential schools. Native communities suffer from extreme poverty and deprivation as treaty rights are ignored and traditional lands are plundered by resource industries.

Wagamese’s compelling novel harnesses two quintessentially Canadian themes, hockey and colonialism, to create an exhilarating and heart-breaking story. Indian Horse reads like “powerful medicine, allowing vital teachings to be shared.”