“All schools for miles and miles around

Must take a special test,

To see who’s learning such and such

To see which school’s the best.

If our small school does not do well,

Then it will be torn down,

And you will have to go to school

In dreary Flobbertown.”

“Not Flobbertown!” we shouted,And we shuddered at the name,

For everyone in Flobbertown

Does everything the same.

It’s miserable in Flobbertown,

They dress in just one style.

They sing one song, they never dance,

They walk in single file.

They do not have a playground,

And they do not have a park.

Their lunches have no taste at all,

Their dogs are scared to bark.

— From Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! By Dr. Seuss, with help from Jack Prelutsky and Lane Smith

Remember Grade 3, when school was all about storybooks and gym class and crafts? We had to learn our multiplication tables and cursive writing, too, but these are not the memories we tend to hang on to. We remember field trips to the zoo, creating elaborate self-expressive collages in art class, playing soccer-baseball in phys. ed, gluing seeds on paper in the shape of butterflies, researching and presenting speeches on whatever topic we wanted, creative group work, and writing and illustrating our own imaginatively colourful narratives.

These activities may be the most memorable, but they are not easily testable. And in a culture that places greater and greater emphasis on testing and accountability, activities that inspire creativity, innovation and imagination are the first to be cut out of the lesson plans when teachers need to make room for more standardized tests and the preparation that accompanies them.

Over the past decade, in the name of accountability, the Canadian education system has followed the American trend toward an invasive culture of rigorous universal testing. Canadian students are being tested more frequently and more extensively than ever before. Every province and territory now mandates some form of provincial assessment program. These tests are generally administered to all students in several grades.

The express aim of standardized testing is to measure the general achievement level of a population of students rather than the specific achievements of individual students. This data is then used as a tool for program review and curriculum development. As a publicly funded system, education needs to be accountable; when universal provincial testing was introduced across Canada in the 1990s, accountability was the mantra repeated by Departments and Ministries of Education. However, the implications of modern testing reach far beyond its original intent.

As provincial assessments have made their way into schools throughout Canada over the past decade or so, they have stirred a lot of controversy. While Departments and Ministries of Education, and their associated testing institutions, insist that standardized testing improves the accountability of our public education system, most of the research on the topic suggests otherwise. Critics of standardized testing point to a long list of cons, including huge financial cost, increased competition between schools, added stress on principals, teachers and students, marginalization of some populations, and the elimination of or decreased emphasis on subjects that are not easily tested (usually social studies, the arts and physical education). Does the value of the data gathered during a few days of testing each year outweigh the drawbacks?

How standard is standardized testing?

A common criticism of provincial assessments is that they aren’t actually all that standardized. For example, province-wide tests in Ontario, developed and administered by the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO), have changed significantly over time. EQAO has responded to criticisms that the test was too long and shortened it from 12 hours to six hours for elementary students. The test questions have become somewhat more accessible to all students – urban, rural, immigrant, ESL. EQAO has also changed their scoring methods, resulting in perceived increases in test scores.

Not only have the tests gotten easier each year, but students have also become better test-takers – with a little focused assistance from their teachers. Many classroom hours are spent practicing how to write the provincial assessments. In recent years, districts have begun to use the scoring data to train teachers to teach “answer formulas” to their students.

In fact, EQAO recognizes this trend. In their “Summary of Results and Strategies for Teachers 2007-2008,” EQAO reports: “Over the last few years, scorers have noted increasing student use of formulas to improve the quality of answers to open-response reading questions… . Scorers have noted that many students have learned these formulas but apply them mechanically (i.e., with little relationship to the text or the question asked). These mechanical answers usually earn a Code 10 or 20 rather than a 30 or 40.”

Not only does this make it difficult to know whether higher test scores actually mean a higher quality of education, it also raises questions about how these tests are training our young people to think and learn.

In the words of Frank Loreto, a teacher in Ontario, “The test does not measure the students’ ability to think or to show knowledge. It is designed to see if kids can follow orders and perform accordingly. Not bad if we were training seals.”

There are also several reported incidents of certain populations of students being strategically left out of testing. In an essay entitled “Targeted Funds and Standardized Tests in British Columbia Aboriginal Schools,” Christine Stewart writes that during the early days of the Foundational Skills Assessment in B.C., “Aboriginal students were often exempt from taking the test. As is often the case, when high stakes are placed on test results, schools tend to excuse those who will bring down school scores from taking the tests.”

Some provinces have addressed this situation by giving students who are exempted from the test a grade of zero, which negatively affects the scores of the school. This has caught some principals off guard over the past couple of years.

What’s in a test?

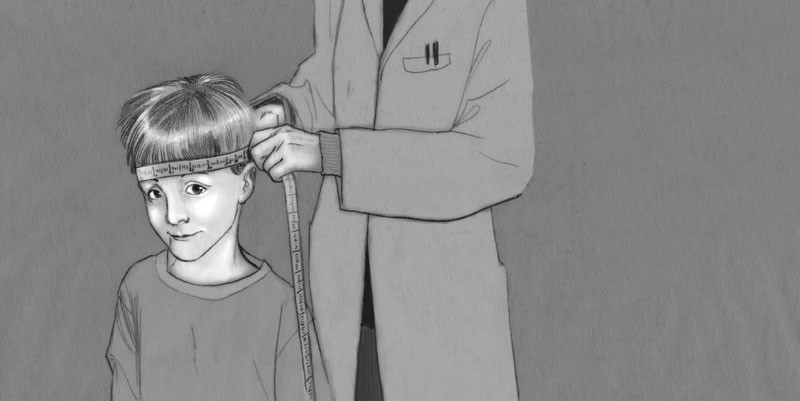

Every province has a different system of tests, but they follow a similar pattern. In Ontario, EQAO tests are administered every year to every Grade 3, 6 and 9 student in the province. There is also a Grade 10 literacy test that must be passed for graduation. This means that, for a Grade 3 teacher in Ontario, the entire school year pivots on one week in May or June when students will write the provincial standardized test. Depending on the school board, teachers may attend extra district meetings, have additional conferences with their principal, be required to attend training sessions, and administer and mark several “practice” tests (sometimes called common assessments) so that predictions can be made about how students will fare come test week.

Jeff Collins, a Grade 3 teacher in Ontario who has been administering the EQAO Grade 3 test since its inception, spends about two weeks actually preparing for the test by teaching test behaviours and reviewing old tests. Throughout the year he teaches the language skills necessary for the test.

“There is absolutely no time for science or social studies during the weeks before EQAO,” Collins told Briarpatch. “It is always a challenge to make sure the entire math curriculum is covered before June.”

Tests are marked by Ontario teachers hired by EQAO, with examinations returned to schools the following school year. According to Collins, “Schools are expected to use the results of EQAO to inform our planning and teaching but I don’t know many teachers that take the results very seriously. We realize that this is a small ‘snapshot’ sample taken in very unrealistic assessment circumstances for eight-year-olds.”

What are we testing, anyway?

In a world of finite time and resources, it’s important to ask what is being left out in order to make room for provincial assessments.

“The time, energy and money that are being devoted to preparing students for standardized tests have to come from somewhere. Schools across the U.S.A. are cutting back or even eliminating programs in the arts, recess for young children, electives for high schoolers, class meetings … discussions about current events … the use of literature in the early grades … and entire subject areas such as science (if the tests cover only language arts and math),” writes Alfie Kohn, a U.S. educator turned author and lecturer, in his essay “Standardized Testing and its Victims.”

“Anyone who doubts the scope and significance of what is being sacrificed in the desperate quest to raise scores,” Kohn continues, “has not been inside a school lately.”

From this perspective, Kohn suggests that high test scores may actually be a cause for concern. He cites a study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology that classified elementary school students as either “actively” engaged in learning (asking questions of themselves and drawing connections to past learning) or “superficially” engaged (copying answers, guessing, and skipping the hard parts). The study found that high scores on two sets of standardized tests “were more likely to be found among students who exhibited the superficial approach to learning.”

So where’s the test that measures how well our children can express what they know about a topic in varied and creative ways?

As Rita Bouvier, Coordinator at the Aboriginal Learning Knowledge Centre of the Canadian Council on Learning, writes in her introduction to the book Assessing Our Ways of Knowing, “Meaningful work and employment, of course, are of immense value; as are reading, writing, mathematics and science – the subjects of current large-scale testing programs. But, equally important are the values which create an ethical premise for life in a community.”

The concern that many teachers and parents are voicing is that the disproportionate emphasis on testable subjects like reading, writing and math is crowding out these valuable life skills.

Adding up the costs

The direct cost of the EQAO testing program is estimated to be between $50 million and $59 million annually. Social, emotional, health and other real educational costs cannot, of course, be measured. Tests place significant pressure and stress on everyone involved, pressure that is compounded as it moves from the Ministry to the Board, to principals, to teachers and, finally and most disturbingly, to students.

Collins, who makes every effort to “have fun” with the test and maintain a low-stress environment in his Grade 3 classroom, has still found that “some students who have had a lot of pressure put on them at home or who have perfectionist personalities … have been very stressed during the test. I’ve had kids hyperventilating and crying despite my efforts to reduce the stress level in the classroom.”

Collins also spoke of the tremendous pressure that teachers in provincial assessment grades feel: “Our school board, like many others in the province, pressures teachers to keep improving test scores at all costs.”

The result of all this stress is that veteran teachers often stay away from testing years, leaving new, inexperienced teachers to teach those grades. In a study by the Alberta Teachers’ Association in 2001, 33 per cent of teachers reported having requested a grade assignment other than grades 3, 6 or 9 – the testing years in that province.

Some critics of standardized testing have called it a tool for discrimination. Although test-makers are reportedly learning how to better accommodate cultural and socio-economic differences, large-scale testing, by its very nature, promotes homogenization and exacerbates class, race, language and cultural differences by defining what type of knowledge is important and how it should be assessed. Rick Hesch, in his essay “Assessing First Nations Students in Math: Potential and Difficulties,” argues that “large-scale standardized testing furthers the project of Eurocentrism and is by definition racist.”

(Mis)use of results

In theory, test results are meant to inform teachers and administrators as they develop future programming, curricula and teaching practices.

The results of provincial and national assessments could help to equalize and standardize our public education system, making it easier for students who change schools frequently. They could act as tools for making better decisions regarding resource allocation, with greater resources being allocated to schools with lower performance levels.

It is important for a public institution to be publicly accountable, but the emphasis placed on quantifying and ranking – and the increasingly common use of results by the public to compare and form opinions about schools – is problematic.

In a handbook for parents, EQAO states, “results should not be the basis for comparisons among schools.” Despite that caution, the Fraser Institute publishes a highly controversial “Report Card” each year that ranks each school in the five provinces (Alberta, B.C., Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick) that make their results public.

Ontario’s Ministry of Education itself recently posted a feature on its website which allowed parents to use a “shopping bag” to compare up to three schools using the data collected from EQAO scores. After public outcry, the shopping bag imagery was removed, although parents can still find the same information on the website, minus the education-as-product symbolism.

Whether Ministries of Education condone it or not, the reality is that parents are using the information published by testing agencies and compiled by the Fraser Institute to “shop” for schools for their children. Anecdotal evidence of this abounds.

The tendency of parents to equate high test scores with higher quality of education is misguided. Virtually all research indicates that scores are far more dependent on socio-economic factors such as community environment, family situation, parents’ educational background and income levels than on any instructional factors.

A 2006 study by the Alberta Teachers’ Association shows that socio-economic status accounts for roughly half the variance in Edmonton Public Schools’ achievement test scores, compared to “school factors,” which account for three to six per cent of the difference in test scores.

If not province-wide assessments, then what?

Is spending tens of millions of dollars each year to test each and every child in specified grades the only way to be accountable to the public? If not universal standardized testing, then what?

First, let’s remember that students and parents already receive regular feedback from teachers via report cards. If accountability is really the goal, then standardized provincial report cards should suffice. They are accountability documents that show parents at regular intervals how their child is doing academically and socially. Ministries of Education could gather report card data from each school district and publish the same information that it gets from the provincial assessments.

In order to determine whether schools are meeting provincial standards, one method that most provinces and territories have employed at some point in recent history is smaller-scale, randomized testing of specified grades.

Countless other progressive options – including portfolio and project evaluations and involving students in the development of assessment criteria – have also been suggested. Many parents and educators oppose the idea of testing entirely, instead encouraging regular verbal and written feedback for each individual student – something that’s much easier to provide when resources are allocated to keeping classroom size down.

Organized Opposition

Teachers and their unions tend to oppose the large-scale implementation of standardized tests. B.C. teachers have been particularly vocal in their opposition to the Foundation Skills Assessment (FSA) for students in grades four and seven, introduced in the mid-90s. The B.C. Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) recently launched a campaign to stop the practice, including sending a pamphlet home to parents informing them of the negative impact of testing on students and encouraging them to withdraw their children from the tests. The result has been an ongoing political battle between the BCTF and B.C.‘s Ministry of Education, with both sides finding allies in the broader community.

The 2009 test results showed over 16 per cent of students having an “unknown” performance level – an indication of the degree to which parents are responding to the BCTF’s campaign by withdrawing their children from the test.

While parental opposition to the tests was often strong and loud when they were first introduced, in most provinces the assessments have now been a standard part of the education system for close to a decade. Parents with school-aged children today haven’t necessarily witnessed the changes in the education system brought on by standardized testing. As a result, active and organized parental opposition to province-wide testing seems to have declined in recent years, as the tests become an established part of the education system.

There are exceptions, of course. One Ontario mother who didn’t want her daughter to participate in the Grade 3 EQAO test this year wound up so frustrated with the process that she started a blog called “EQAO Must Die,” where she documented the complex series of bureaucratic hoops she was forced to navigate, to little avail, in her attempt to exempt her daughter from the test. There are also several Facebook groups founded by parents and students in opposition to province-wide tests.

People for Education, an active and respected parent-led organization that advocates for improved public education in Ontario, staunchly opposes the current system of province-wide testing in that province. Their “Annual Report on Ontario’s Schools 2008” points out that “we have had little discussion about what kind of results we’re looking for… . What kinds of students do we want to graduate? What knowledge and skills do we want them to possess, and are there some qualities we want them to have?”

Almost universally across the country, provincial education targets are tied to students’ test scores in reading, writing and math. But since “business and community leaders say we require more innovators and creative thinkers,” People for Education’s 2009 Annual Report asks, “Shouldn’t there be more to it than that?”

Well, shouldn’t there be?