Dying from Improvement: Inquests and Inquiries into Indigenous Deaths in Custody

Sherene H. Razack

University of Toronto Press, 2015

In early April 2016, Attawapiskat First Nation declared a state of emergency when 11 young people tried to kill themselves in one day alone. The response from the state was to send in crisis workers. As I write, occupations and protests have erupted across Canada to draw attention not only to youth suicides in First Nations communities, but also to the state’s response to them. As protests continue, the state’s reactions to these situations raise alarming questions about its relationship with Indigenous peoples. On April 10, Justin Trudeau tweeted, “The news from Attawapiskat is heartbreaking. We’ll continue to work to improve living conditions for all Indigenous peoples.” We, the state, will work to improve living conditions for all of you, Indigenous peoples. Taking a page out of an old paternal script, the state sees itself as the champion that can deliver improvement – and, in doing so, it erases its own direct role in inflicting the ravages of structural violence in the long history of this settler state. Against this backdrop, Sherene Razack’s Dying from Improvement is a critical intervention, as it provides an analysis of the banality of settler-state violence framed through narratives of improvement and inquiry.

Focused on the testimonies and transcripts from inquests and inquiries into the deaths of Indigenous peoples in police custody, Razack’s book begins with the story of Paul Alphonse, a Secwepemc man from B.C. Following a days-long search, family members finally found him in police custody in a hospital. Alphonse’s niece noticed a purple bruise in the shape of a boot print in his chest, but no medical practitioners had noted it. Alphonse later died, and the subsequent inquest into his death focused on his alcoholism and damaged body, treating the boot print as a secondary element rather than evidence of violence. Alphonse was a residential school survivor struggling, like many others, with the legacy of that colonial program. His family tried to raise this context in the inquest, but it was bracketed out of the discussion.

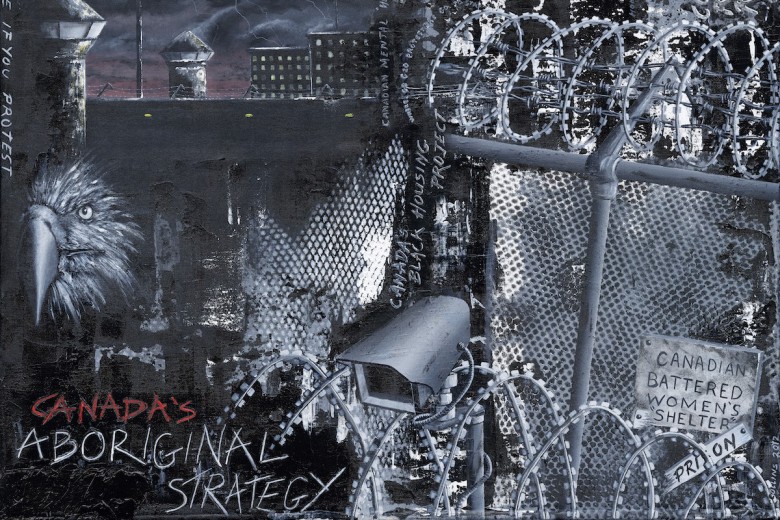

The inquest and investigation into Alphonse’s death becomes but one of a long list of cases that reflect the state’s leveraging of legal apparatuses to treat deaths in custody as ruminations about damaged bodies. These bodies are always already dying; they are bodies that pose risk to those who encounter them (police and medical professionals), bodies that are out of place (in the cities), and bodies that are out of order (characterized as drunk and diseased). Razack writes: “Through a legal performance of Indigenous people as a dying race who are simply pathologically unable to cope with the demands of modern life, the settler subject is formed and his or her entitlement to the land secured. The settler and the settler state are both constituted as modern and as exemplary in their efforts to assist Indigenous people’s entry into modernity. In this way, killing becomes saving, and murder becomes redemption. Law is absolutely crucial to this alchemical transformation.”

Razack’s framework centres the ongoing violence toward Indigenous bodies and the dispossession of land. The inquest, commonly seen as a tool of accountability, is redelivered as a tool of the state that serves to enact violence upon Indigenous bodies long after they have died in custody.

She emphasizes not only the many in-custody deaths of Indigenous people (an eight-page appendix offers details of 116 deaths between 1990 and 2010), but also, even more specifically, how these deaths can tell an interlocking story of settler colonialism, conquest, and capitalism. In this system, Indigenous bodies are framed as broken and disposable, ensuring that all interventions preclude an investigation into the central role of colonialism.

This is a book that demands to be read. While written for the University of Toronto Press, Razack’s case-study approach is relatively accessible. The critical theory, underpinned by Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben, is relatively muted; this approach appears intentional, to appeal to a wide readership. That said, some readers might be frustrated with the relative absence of a more rigorous theoretical engagement. Razack also seems to write for a settler audience and demands that they think about their own racism and complacency in these narratives and systems. This can be tough work for many, as it requires a critical analysis of self. Having taught with this book in an undergraduate class, I can say that Dying from Improvement succeeds in making the reader think.

Razack’s book is a sharp indictment of the supposition of improvement – including the kinds of promises of improvement embedded in the prime minister’s tweet. The current protests in Canada, a response to the demands of the youth of Attawapiskat, serve as an anchor for Razack’s call to reject the benevolent state and instead focus on self-determination for Indigenous peoples. She closes with a resonant sentiment: “If we start with the reality of an ongoing colonialism, we can better reflect on the inhumanity that such a project requires. Then and only then will we be able to reject the fantasy of settler civility and refuse the game of improvement.” Trudeau’s commitment to improvement is a stark reminder of the violence that is effaced when the state appears to furrow its brow in concern.