A crowd gathered around the statue of Sir John A. Macdonald in Kingston’s City Park at noon on January 11, 2017, the birthday of Canada’s first prime minister, who represented Kingston in Parliament for nearly five decades pre- and post-Confederation. Those assembled were not celebrating Macdonald’s birthday, but rather the fact that for the first time in years there was no official birthday toast to Macdonald. In effect, they were celebrating silence – a victory after five years of organizing.

Kingston was Macdonald’s hometown, and it served as the first capital of the united Province of Canada from 1841–44. This eastern Ontario city, which is situated on traditional Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee territory, has played a unique role in Canada’s colonial history, and it is certainly proud of its heritage. But that heritage has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years thanks largely to the work of Idle No More–Kingston, ON/Katarokwi (INM–K).

Widely celebrated among settlers as the driving force behind Confederation, Macdonald is notably exalted in Kingston, where numerous buildings and streets are named after him; yet recent literature, such as James Daschuk’s 2013 book Clearing the Plains, has meticulously documented Macdonald’s calculated colonial policies, including genocidal starvation of Indigenous nations that enabled the expansion and settlement of Canada, and his early support of residential schools.

In Kingston, tension over the annual birthday toast came to a head in 2016, when Arthur Milnes, the event’s organizer and a former speechwriter for Stephen Harper, had the tires of his car slashed and a burned Canadian flag discarded at his home; the vehicle of Liberal MP Mark Gerretsen was also vandalized. INM–K burned an effigy of Macdonald at that year’s toast. They claimed no responsibility for the vandalism but readily note that the resulting controversy and national media attention helped to raise their profile and renew debate about Macdonald’s legacy.

“Every action needs multiple fronts,” says Beth (a.k.a. Krista Flute*), a Lakota and Cajun woman who is a tireless organizer with INM–K and was displaced to Kingston-Katarokwi by the Scoop, an ongoing process begun in the 1960s in which Indigenous children have been disproportionately taken from their families by child welfare workers. She is quick to point out that what is considered acceptable protest behaviour and what is classified as violent conduct has changed in recent decades, and she argues that the suppression of militant forms of protest is akin to the suppression of her people’s legitimate anger. She spent a summer in her youth helping run supplies to Mohawk warriors in Oka during the Resistance of 1990, and she sees reverence for peaceful non-violent protest as a privileged stance that disregards the reality of colonial violence. “Colonialism is war; our people are dying. Since when are people not allowed to defend themselves in war?”

Although INM–K celebrated victory this year, they know their work of raising the profile of Macdonald’s racist and genocidal actions is far from complete. Beth acknowledges that the narrative surrounding Macdonald has become more nuanced in recent years, but she is adamant that on a whole he is still portrayed favourably. “He committed genocide, started residential schools, the Indian Act, the pass system, but he’s still a good guy? He’s the father of Apartheid.”

INM–K hopes to see his statue removed from City Park altogether, an increasingly plausible outcome given the conspicuous absence of a 2017 birthday toast and the decision to remove a statue of Macdonald at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, last year. Macdonald is an important target not just because of his own history, but because of what he represents in Canadian history: “the beginning of Canada, the start of the colonial state,” explains Beth. “Helping people to understand that it’s not okay to glorify such a man is part and parcel of helping people to realize that it’s not okay to glorify a colonial state.” In other words, as the façade of Macdonald is stripped away, so too is the underlying mythology of Canada as a benevolent and all-inclusive nation.

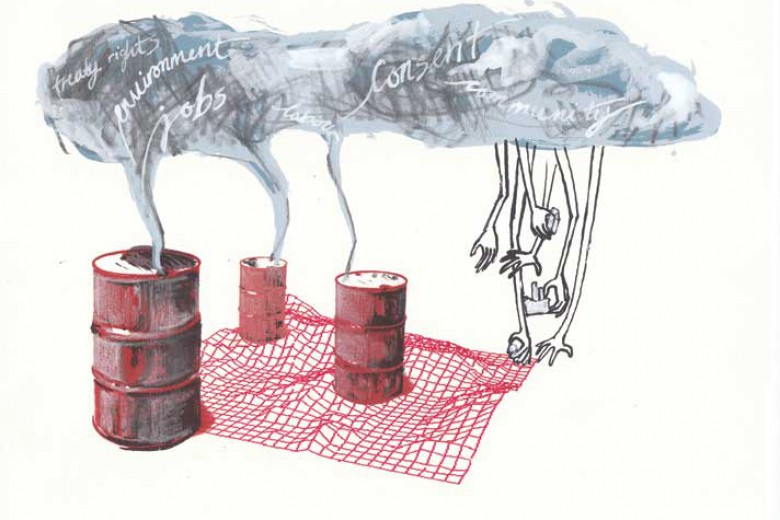

INM–K has also opposed Canada Day celebrations, held an annual vigil for missing and murdered Indigenous women, organized in solidarity with anti-pipeline groups and others, and hosted workshops and discussions on topics like allyship and direct action. Their tactics, such as publicly burning a Canadian flag on Canada Day in 2016, have not always won them positive press, and their distrust of the political process has at times put them at odds even with other activist groups in the area. Indeed, Beth says that the point of organizing is not to engage with politicians, who she says will never be interested in anything more than a “nicer colonialism that is more palatable for middle-class Canadians.” Instead, INM–K is focused on public outreach and education. The point, Beth adds, is “to build a revolution.” That means waking up more people to Canada’s colonial reality and bringing together more allies, ultimately fertilizing the ground for radical decolonial action.

“Helping people to understand that it’s not okay to glorify such a man is part and parcel of helping people to realize that it’s not okay to glorify a colonial state.”

For example, leading up to the bicentennial celebrations of Macdonald’s birthday in 2015, INM–K took note of SALON Theatre, a local troupe popular for its dramatized historical walking tours and its celebratory John A. Macdonald musical, Sir John, Eh? SALON was developing new material for the bicentennial, and Paul Dyck, artistic director at the time, acknowledges they were working with “a pretty positive view of John A. Macdonald.” INM–K engaged with SALON over the exaltation of Macdonald underpinning their work.

“I think the biggest thing we learned was that history isn’t black and white, it’s really complicated, and you really have to put yourself in many people’s shoes to view the entire process that was the creation of Canada,” says Dyck. He was motivated to move the story beyond the typical celebratory tone, and reached out to a number of people and groups in the community for input into the process. One result was The Trial of Sir John A., a new play emphasizing Macdonald’s colonial legacy, including the settlement of the west.

In light of this year’s Canada 150 celebrations, Beth insists that INM–K has made clear that the group will stand in opposition to colonial celebrations. “We’ve been active and vocal enough for the city to understand what a colonial event is,” she adds. While the city has predictably planned a massive birthday party, INM–K hopes to use Canada 150 as an opportunity for engagement. “I want us to think about what we need to do individually and collectively to decolonize, because that’s something we are simply going to have to go out and do, and we need to go out and do it before it’s too late and the Earth does it for us.”

Beth emphasizes the urgency of sparking change. “I think the only reason people say we won’t see it in our lifetime is because we’re not doing it. How is the next generation going to do it if we don’t show them how?” INM–K has not shied away from leading with action. To challenge Macdonald on his home turf is bold and necessary if we are to confront the persistent myths that obscure Canada’s colonial reality. INM–K has undoubtedly made headway that offers a model for uncompromising and persistent organizing.

*Born Krista Flute, Beth is her given name after being adopted through the Scoop; she continues to grapple with her identity and uses both names.