When Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence declared that she would begin a hunger strike in early December of 2012, one of the largest Indigenous-led social movements was already roaring across the country. At the heart of Idle No More was a call for an honest treaty relationship. The Harper government had advanced a series of legislative measures amending the Indian Act, Fisheries Act, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, Navigable Waters Protection Act, and seven other laws directly affecting First Nations, all without consultation. These measures would dramatically erode treaty rights by paving the way for industrial development on Indigenous lands.

Idle No More galvanized mass demonstrations of Indigenous people, which included a variety of protest actions throughout Canada, the U.S., and beyond. Describing the movement as “bacteria,” the RCMP monitored 941 events associated with Idle No More – rallies and infrastructure blockades – between December 2012 and May 2013. In addition to the demonstrations descending on Parliament Hill, Spence went on a six-week hunger strike on nearby Victoria Island while demanding a nation-to-nation meeting with the Crown to discuss the treaty relationship.

Spence’s demands directly challenged the existing asymmetrical relationship based on settler domination and control over Indigenous peoples, lands, and resources. In response, government officials sought to delegitimize Chief Spence and Idle No More. Aboriginal and Northern Development Canada (AANDC, now called Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada [INAC]) leaked an audit report, in a move that was widely viewed as a smear tactic to discredit Spence in the lead-up to the anticipated meeting, organized for January 11. The government also referred to oppositional chiefs as “dissident chiefs” – “those chiefs that reject the AFN [Assembly of First Nations] direction and favour the use of more aggressive, possibly more radical, means of motivating the Canadian government.”

Spence’s demands directly challenged the existing asymmetrical relationship based on settler domination and control over Indigenous peoples, lands, and resources.

How do we know? Internal government files I obtained through the Access to Information Act (ATIA) reveal how the Canadian leadership and bureaucracy interpret Idle No More, and treaty obligations more broadly.

Instead of the meeting with the Crown to discuss the treaty relationship demanded by Spence, Harper agreed to a “high-level dialogue on treaty relationships,” which was internally characterized as a “private working meeting.”

Spence ultimately did not attend because the representative of the Crown, the Governor General, would be absent, though she did attend a “ceremonial” meeting later that day with David Johnston.

The meeting with Harper carried on without Spence, though the public’s reaction to it was explosive: chiefs from Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan boycotted the meeting in part over the absence of the Governor General and pressured then-AFN Chief Shawn Atleo to do the same, claiming he had no mandate to discuss treaty rights without treaty chiefs present. Meanwhile, protesters tried blocking the entrance to the building where the meeting was to take place, and Indigenous women linked arms to prevent the chiefs from entering. CSIS records reveal an intelligence meeting held three days earlier, on January 8, in which security experts condescendingly predicted that less than one third of the 1,200 who indicated attendance on a Facebook event page “will actually show up.” But they were wrong: according to RCMP email records, the “immense protests” that coincided with the meeting – with approximately 3,000 participants, according to an RCMP situation report – created a “fluid and volatile” situation for the government.

The ministers’ education

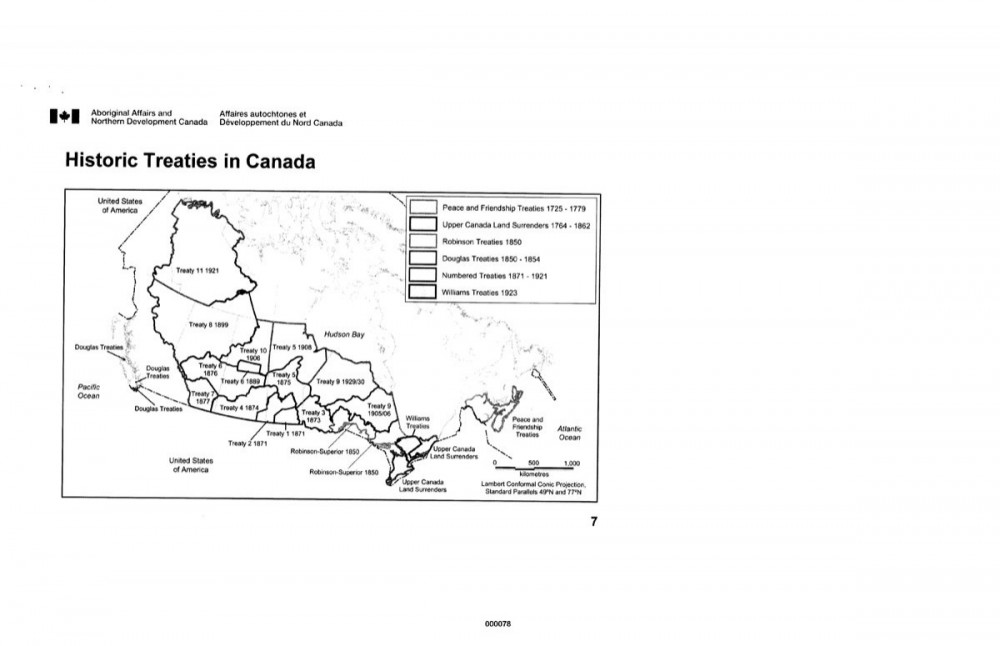

Ahead of the meeting, AANDC prepared a presentation called Historic Treaties in Canada: Overview for Ministers. These presentation slides describe historic treaties as the roughly 70 agreements signed before 1975, covering nearly 60 per cent of the territory of Canada. The slides characterized the historic treaties as “largely fulfilled.”

The AANDC files explicitly state the goals of settler-colonial treaty making as the settlement of the land and establishment of Canadian sovereignty. Canada’s position is that “historic treaties extinguished Aboriginal rights and title in return for the promise of specific rights and benefits for those First Nations who were signatories to the treaties.” Prior to Confederation, treaties were, according to the government, concluded to “defend the colonies and open the lands of the Great Lakes to settlement.” After 1867, “treaties were concluded to secure Canada’s sovereignty over the West” and “open the lands for settlement.”

The meeting would be considered successful if the treaty relationship could be used to the government’s advantage, “particularly in the context of removing obstacles to major economic development opportunities.”

AANDC identified that Canada’s key objective for the meeting was the negotiation of economic development in Canada’s interest: “the agenda will also address key federal priorities related to resource development, addressing barriers to First Nations participation in the economy, and a results-based approach to treaty and self-government negotiations.” The meeting would be considered successful if the treaty relationship could be used to the government’s advantage, “particularly in the context of removing obstacles to major economic development opportunities.”

In its slides, AANDC admits that “the treaties were concluded to share the wealth of the land to the benefit of both parties, guarantee assistance in times of need and secure their economic well-being.” It remains to be seen how this point can be reconciled with a report produced by INAC’s Strategic Research Directorate that compares “community well-being” (which measures education, income, housing, and labour force activity) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The report finds that Indigenous community signatories to historic treaties rank the lowest: “Among the ‘bottom 100’ Canadian communities, 96 were First Nations. At the same time, only one First Nation community ranked among the ‘top 100’.”

Zoe Todd, who is Red River Métis (otipemisiw) from Amiskwaciwâskahikan/Edmonton, Treaty 6, and assistant professor of anthropology at Carleton University, points out the problem with the state’s treaty distortions: “A treaty can’t be fulfilled if Canada doesn’t consider it a living, ongoing set of relationships and responsibilities that have to be renewed continuously between the people that are bound up within them or who are party to them.”

Todd understands Treaty 6 as “an agreement across legal traditions between two sovereign nations or peoples.” The underlying principles of reciprocity that guided treaty making, she explains, have been “abandoned quite completely, especially with things like the Indian Act and forced removals of people from their lands and the ongoing destruction of Indigenous land in the name of extraction, and oil and gas, and mining and pipelines.”

Susana Deranger, who lives in Regina and is an experienced Indigenous activist from the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, explains, “It was never about ceding land and in fact all the rights that came with treaty making were to be over and above everything that we already had.” She adds, “Treaties in no way, shape, or form have ever been recognized or dealt with properly [by the Canadian government].”

Internally, AANDC was quite plain about why that is: the “primary intent was to secure Crown title over lands and resources.” The department goes on to say, “consequently, the Crown holds that it has: unfettered access for settlement and development; full ownership of all resources and benefits; only needs to consult in cases relating to defined treaty rights,” and that Crown “rights and obligations are limited by the text of the treaties.”

The AANDC slides ultimately conclude that “Canada’s policy on Treaties remains in opposition to First Nations perspectives,” and that “the fundamental issues regarding the intent, interpretation and implementation of treaties have been the primary roadblock to establishing a more workable relationship with Treaty First Nations.”

The slides also amount to a stark admission that treaties represent to Canada the outright ownership of Indigenous lands for the purposes of extracting resources and wealth. Prepared for a discussion about treaty rights at the height of Idle No More, the slides revealed that from the government’s perspective, treaties were not, and are not, an agreement between two sovereign nations, but rather a deceitful exercise in expropriation of land for the benefit of the settler state.

The deceit trajectory

What does the revelation about Canada’s interpretation of historic treaties mean in light of the government’s current modern-day treaty negotations with First Nations? Almost five years after the inception of Idle No More, a new prime minister is at the helm, but the state’s underlying position on treaties has remained constant, evidenced by Trudeau’s approval of several energy projects on Indigenous land without Indigenous consent.

Recently, at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in May 2016, INAC Minister Carolyn Bennett declared, “We intend nothing less than to adopt and implement the [United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – UNDRIP] in accordance with the Canadian Constitution.” However, she continued, “Canada believes that our constitutional obligations serve to fulfil all of the principles of the declaration, including ‘free, prior and informed consent.’ We see modern treaties and self-government agreements as the ultimate expression of free, prior and informed consent among partners.”

First Nations policy analyst and consultant Russ Diabo sees the government’s modern treaty negotiation process as a “termination plan.”

What does the revelation about Canada’s interpretation of historic treaties mean in light of the government’s modern-day treaty negotiations with First Nations?

According to Diabo, “In exchange for roughly $25,000 per person and 10–15 hectares of land under the modern treaty framework, signatory communities must accept the 1867 constitutional framework, which means federal and provincial laws apply.” He explains, “Basically, that means you only have local or municipal-type powers left over to negotiate; they call that ‘harmonizing of laws’.”

Indigenous rights and title are basically converted “from pre-existing sovereign rights into post-treaty defined rights,” he says.

Diabo explains that other modern treaty framework preconditions include releasing Crown liability for past violations, eliminating reserves by accepting lands as private property, removing on-reserve tax exemptions, and respecting existing third-party (industry) interests.

There are currently around 100 such modern treaty negotiation tables open in Canada; the negotiations cover geographic areas where historic treaties were never signed and Indigenous title was not extinguished.

For Todd, settler anxieties surrounding UNDRIP and upholding the terms of the treaties demonstrate the fragility of Canada’s claim to sovereignty over Indigenous lands (this likewise applies to the other three states that originally voted against UNDRIP – the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand).

“They need to keep denying Indigenous sovereignty and they have to ignore the weight of the treaties in order to keep enacting the fiction that is Canadian sovereignty over Indigenous lands.”

Deranger argues, “People deep, deep, deep in their consciousness know that these lands are Indigenous lands and they are really, really afraid that if they ever give an inch, everything will be taken back.”

The existence and prosperity of Canada is and has always been dependent on the theft of Indigenous land and resources, which requires obfuscating the spirit and intent of the original treaties, dismissing current international frameworks such as UNDRIP, and promoting a modern treaty framework that eliminates Indigenous rights. Treaty making defines Canadian-Indigenous relations and, from the perspective of the colonizers, no matter which administration is in power, treaties assert Canadian sovereign authority over Indigenous peoples and land. The AANDC documents expose the Canadian state’s view of Indigenous peoples as obstacles rather than partners.

The prosperity of Canada has always been dependent on the theft of Indigenous land and resources, which requires obfuscating the spirit and intent of the original treaties.

The AANDC documents also reveal a firmly entrenched government position that the Canadian state enjoys full ownership over Indigenous land and resources through the treaties.Unpacking some of the Liberal rhetoric reveals the government’s steadfast determination to negotiate the ceding of Indigenous land under the auspices of “nation-building.” In June 2016, Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould declared to an AFN audience that nation-building would be supported in the context of the historic treaties. In light of the government’s interpretation of historic treaties, this framing portends control and exploitation of Indigenous lands and communities well into the future.

While Indigenous histories, legal traditions, and activists push back, and as treaties are publicly recognized as nation-to-nation agreements and not a ceding of Indigenous rights, colonial governments will have to contend with greater, and increasingly vigorous, resistance. Idle No More mobilized unprecedented power while revealing the nature of the government’s political position vis-a-vis its relationship with Indigenous peoples. Knowing with certainty that the government’s internal position contradicts its public declarations is valuable intel for anti-colonial movements building broad, informed resistance for the next 150 years.