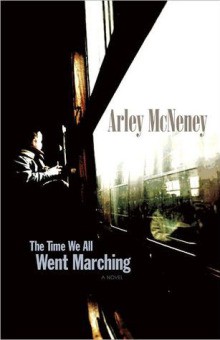

The Time We All Went Marching

By Arley McNeney

Goose Lane, 2011

The last spike was driven in the transcontinental railway in 1885, satisfying a commitment made to British Columbia by the Canadian federal government. The railway would unite the Confederation, open up new lands for colonization, and provide greater access for industry and trade. Fifty years later, in June 1935, hundreds of unemployed men took to those same rails in what was dubbed the On to Ottawa Trek.

In response to staggering unemployment rates during the Great Depression, the federal government set up isolated relief camps where single, jobless men toiled in poor working and living conditions. Thousands of these men walked out in April 1935 and boarded boxcars heading to Ottawa to raise their demands with the government of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett. The march was crushed in Regina when a police riot against the Trekkers ended with two people confirmed dead and over 100 arrested. This is the historic moment in Canadian working peoples’ history referred to in the title of Arley McNeney’s beautifully written second novel.

The Time We All Went Marching is composed of vignettes that move back and forth through time and from character to character, bringing the struggle of working-class men and women in the 1930s and 1940s to life through luminescent prose.

The story begins in the aftermath of the Second World War as Edie takes her four-year-old son, Belly, and boards a train bound for New Westminster, B.C. She leaves Slim, her husband of 10 years, passed out in their apartment covered in ice and snow from an open window and a burst pipe.

Throughout the journey, Edie spins stories for her son, and for herself, about the On to Ottawa Trek. She relates how the men lacked placards and so used shoe polish to write slogans – We Want Work and Wages! End the Slave Camp System! – on their clothes. “They wear their sweaters until the letters bear their scent,” McNeney writes, “until the sweat bleeds the message imprecisely onto their damp skins.”

Slim’s stories of taking part in the Trek were what first captivated Edie. She returns to these stories after leaving him behind, retelling Slim’s story the way she imagines it. And she tells it wonderfully: “Slim knows that the train can confuse your body so much it thinks it’s been airborne. He knows the way your legs reject solid ground when you’ve been moving so fast for so long.”

The lyrical rhythm of the prose and the working-class subject matter prompt favourable comparisons to Michael Ondaatje’s classic novel In the Skin of a Lion, but the story lacks Ondaatje’s narrative drive. It is not until a quarter of the way through that the story picks up a solid pace. An accident on the train leaves Belly injured, and the passengers are forced to stop in a snowbound saloon. Even then, the drama and conflict feel muted.

Unfortunately, the almost-phantasmic vignettes and twisting narrative threads that are the novel’s strength work against building needed suspense. McNeney’s treatment of the Regina Riot as a memory retold by Edie, a non-participant, brings poetry to the experience but lessens the tension.

Ultimately, this is not a peoples’ history but the story of one woman on the cusp of change. Edie has made a bold decision to break with her current life. However, instead of looking to her future, she spends the journey returning to the past: her teenage love affair with a prisoner in a graveyard, and her first years with Slim when she disguised herself as a miner to keep him company in the tunnels.

Edie also wrestles with her ambivalent feelings toward her son. McNeney acknowledges that rearing children can be a burden as easily as a blessing, and that this burden may not always be overcome by a mother’s love. Edie loves Belly but yearns for the freedom to pursue the wildness within her. “There are those who want to ascend in life and those who want to move straight and fast as far as they can go: those who seek clouds and those who seek the sun setting along a horizon they will never touch. Edie believes that the world can be divided into those who dream of walls and those who dream of trains.”

A train is a machine with unwavering purpose; it moves relentlessly forward on the rails. If the cars leave the track, there is no escaping disaster. Unlike a train, McNeney’s beautiful novel takes time to meander; the prose jumps ethereally off track, and patient readers will find themselves richer for the derailment.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)