U.S. social movement theorist Frances Fox Piven says that successful social movements emerge not just when people experience hard times but when they start to believe that fighting back is both legitimate and possible. The two most significant mass mobilizations in Canada in recent years – Idle No More and the Quebec student movement – have both embodied these qualities despite their great differences in structure and make-up. In each case, the participants knew that their cause was righteous and they believed they could accomplish something through defiant, collective interruptions of everyday life.

According to Piven, social change is less a matter of steady calculation and incremental build than punctuated disruptions that burst into view and only sometimes coalesce in more stable organizational structures (which themselves will inevitably need to be disrupted and unsettled).

The advances of feminist struggles in the West are commonly understood through the metaphor of three giant waves that have swept through society. In the cover story for this issue, Aalya Ahmad asks if this wave metaphor is the best frame for understanding feminist activity today. Responding to Toronto Star columnist Heather Mallick’s complaint about the lack of “prominent young feminists” in Canada, Ahmad addresses the public bind feminists face. While globetrotting celebrities, neoliberal politicians, and corporate executives may be championed as feminist heroes today, women on the ground who are participating in the most vital feminist initiatives remain largely invisible.

In conversation with five other feminists, Ahmad asks if our very ways of looking at feminism need to be rethought in light of the particularities of low-income organizing and Indigenous women’s struggles, as well as the recent prominence of organizing around sex work and the oppression of transgender people – activism that addresses “deeply painful and challenging fault lines in historical feminist movements.” Ahmad notes that professionalization, meanwhile, can have a hollowing effect.

This is not unique to feminism. For reasons that aren’t mysterious, progressive organizations that have significant resources and capacity tend to be the most averse to risk, to escalation, and to creativity. Such organizations have a tendency to patronize and poach youth rather than add oxygen to their fire. Theirs is a model of gradual, incremental change within the system, directed from above by people with plenty of job security and little rage. As the confines of the system itself narrow, inevitably so does the vision of such organizations.

One of the liabilities of the welfare state for feminism in Canada has been that much of the movement became reliant on government funding. State resources and legitimacy dramatically expand capacity, but finance ministers can yank it all away like a rug with the snap of a budget. Meanwhile, the welfare state itself has always been a colonial weapon for dispossessing Indigenous women. The very words “social services” signal state abductions, abuse, and trauma for Indigenous people.

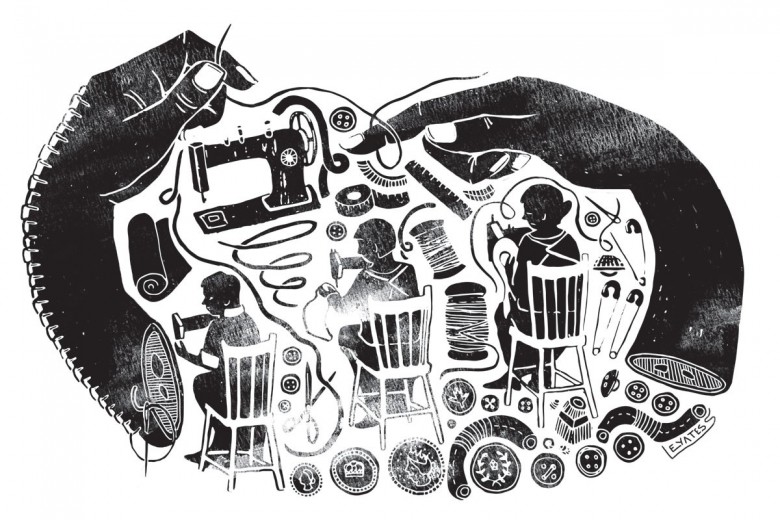

In response to Mallick’s complaint, Ahmad cites not only feminist projects but mass mobilizations that have been “chock full of strong activists concerned with gender and equality issues.” And the truth is that the actual work of movement building is always disproportionately borne by women and queer people. It’s certainly true of the bulk of all grassroots organizing activity everywhere that I’ve lived. From outreach, planning, and event logistics to facilitating, skill-sharing, and the endless emotional labour of building relationships, easing interpersonal tensions, and lending caregiver support, women do most of the grunt work on the left, while pushing a giant Sisyphean rock of feminist pedagogy in front of them every step of the way.

My friend Chelsea Taylor says that women organizers in the Occupy encampment in Edmonton developed a shorthand to describe some of the men who joined. New to activism and unconsciously armed with an arsenal of patriarchal assumptions and gendered behaviour – narcissistic posturing, poor listening, an aversion to menial tasks – there are male activists who require days, weeks, months, and years of patient, repetitive coaching simply to become tolerable. Chelsea and her comrades referred to such men as “500-hour guys.” As in, “Sigh, here comes another 500-hour guy. Can someone else please take the first shift with him?”

Over the years I’ve learned that the left mirrors the rest of society in that its loudest voices often belong to men who do little or none of the actual legwork that makes shit happen. Whether progressive change happens like Piven says it does – through punctuated social disruptions that defy the tenets of existing organizations and their leaders – or whether stable membership-based structures are essential for real gains (or, more likely, if both are true), we all have a role to play in building movements in which feminism is a practice and not just a conversation topic or a public pose, and where being a guy doesn’t mean outsourcing all the menial tasks and emotional support work to others.