Back in May 2020, Lenapehoking – where so-called New York City, where I live, is situated – was at the epicentre of the growing global pandemic. Every day felt more daunting than the last. Case numbers climbed and more folx became sick, many never recovering. There was a flurry of calls for mutual aid, and more folx, including myself, began to organize our communities. We were bracing for the impacts of COVID-19 and also for the way we knew the pandemic would amplify existing issues like unemployment, predatory landlords, and policing.

As calls for solidarity and community organizing were answered through expansive mutual aid efforts, those efforts – and the history of mutual aid – were inevitably co-opted. White gentrifiers began what they called “mutual aid” networks without consulting the Black and brown communities whose lands and neighbourhoods they occupied; museums collected objects related to mutual aid without offering fiscal support or reciprocity; and non-profits stole the work of grassroots organizers to placate their funders. There was a lack of consultation with the communities most impacted by COVID-19. In response to that co-option, I wrote a zine called “Let’s Talk Mutual Aid” to help combat the misinformation around what mutual aid is and is not. Here, I expand on what I wrote in that zine, updating it for our current context more than a year into the pandemic.

What is mutual aid?

Mutual aid is simple: it’s breaking the binary of the “haves” and the “have-nots” by equitably reallocating resources and knowledge. In an article for The Cut, Amanda Arnold defines mutual aid as “a form of solidarity-based support, in which communities unite against a common struggle, rather than leaving individuals to fend for themselves.” What Arnold’s article fails to mention is that mutual aid is also a commitment to anti-capitalism. Capitalists cannot practise mutual aid; they can practise temporary reallocation (i.e. philanthropy) which is not the same as an anti-capitalist commitment to community thrivance. Mutual aid is not charity.

Mutual aid defies the hierarchies and white saviourism inherent to charity, instead asking us to share our skills and resources in order to decentralize community care, and help one another break free from capitalism and colonial authority.

Dean Spade, author of Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During this Crisis (and the next), writes that “The charity model we live with today has origins in Christian European practices of the wealthy giving alms to the poor to buy their own way into heaven. It is based on a moral hierarchy of wealth – the idea that rich people are inherently better and more moral than poor people, which is why they deserve to be on top.”

Mutual aid defies the hierarchies and white saviourism inherent to charity, instead asking us to share our skills and resources in order to decentralize community care, and help one another break free from capitalism and colonial authority. It can look different in different places, taking into account local community and cultural protocols. It also demands that we treat each other as responsible and meaningful contributors, so it often includes reciprocity and resource exchange (though not immediately or always).

Mutual aid is a long-term commitment to your community. It must be sustained beyond times of obvious crisis, emergency, or pandemic, into times of normalized poverty and racism. Those who were not practising mutual aid before COVID-19 need to understand that they must commit to mutual aid beyond COVID-19.

Because BIPOC are the most adversely affected by COVID-19, anyone looking to practise meaningful mutual aid right now is obligated to learn from the histories that have shaped the practices we embrace in times of crisis.

When I wrote my zine, I wanted to address the fact that there was little to no discussion, especially by white organizers, about how Black people, Indigenous people, and people of colour (BIPOC) have been criminalized for practising what we currently call “mutual aid.” Ignoring the history of BIPOC mutual aid furthers the narrative that our communities are “uncivilized” and unable to take care of ourselves without settler meddling, and it encourages white saviourism. It also contributes to the ongoing erasure of the violence perpetrated by white settlers on BIPOC communities. Because BIPOC are the most adversely affected by COVID-19, anyone looking to practise meaningful mutual aid right now is obligated to learn from the histories that have shaped the practices we embrace in times of crisis.

Many white organizers will have you believe that mutual aid is an anarchist-communist theory based in either autonomous independence from the state or in workers’ rights. Though mutual aid does encompass those things, it is important that people understand that mutual aid has always been a BIPOC tradition. Often, people will cite the Russian revolutionary Peter Kropotkin as the father of mutual aid. Though his work has inspired many radicals, he was not the source of the entire practice and theory of mutual aid. Arnold made the same mistake in her article in The Cut, rooting mutual aid in Kropotkin and the work of white anarchists of the 19th century, followed up by an incomplete explanation of BIPOC mutual aid.

The reality is that mutual aid has its roots in community resistance by Black and Indigenous people, who have been criminalized for these exact practices that are now celebrated by the white mainstream.

Criminalization of mutual aid in BIPOC communities

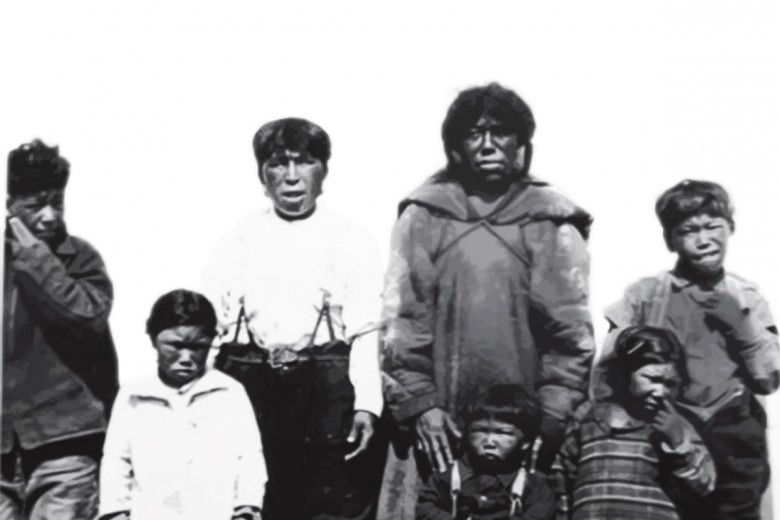

In so-called Canada from 1885 until 1951, Indigenous communities of the North West coastal regions – like the Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw – were forbidden from practising their gift-giving ceremony of Potlatch. Under the Potlatch ban, Indigenous communities were punished for their anti-capitalist tradition with mandatory jail sentences if caught practising potlatch. Even so, many communities continued the tradition underground.

On December 25, 1921, 25 Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw community members from ‘Mimkwamlis were arrested and charged under the Criminal Code for breaking the Potlatch ban. Twenty Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people were sent to Oakalla Prison in the Lower Mainland and served two- to three-month sentences for practising their tradition. It is important for non-Indigenous people to understand that the criminalization of our ceremonies is a tool used by colonizers in our ongoing genocide.

When Black and Indigenous people work to end their communities’ dependency on the settler state through community care, they threaten the foundations of settler colonialism and capitalism.

It is no coincidence that our inherently anti-capitalist ceremonies are seen as a threat to the colonial status quo: they prove that alternative lifeways are possible. Mutual aid invites community members to take care of one another through shared respect and accompliceship, ending our dependency on waged labour and profit. It ushers in community sufficiency, challenging us to share – rather than hoard – wealth and land. The belief that land can be owned is inherently colonial, and a lack of access to the resources of the land is why communities need mutual aid in the first place. In the settler-colonial state’s drive to dismantle and destroy Indigenous Peoples’ ability to be self-sufficient, the theft of land is its most obvious tactic.

For a more recent example of government interference in mutual aid efforts led by people of colour, we can look to COINTELPRO’s infiltration of the Black Panther Party in the so-called United States. COINTELPRO was a series of secret projects in which the FBI spied on, infiltrated, defamed, and murdered members of political organizations from 1956 to 1971. COINTELPRO specifically targeted individuals and groups that the FBI deemed subversive, including feminists; anti-Vietnam War organizers; and activists of the civil rights movement like the Black Panthers, American Indian Movement, and the Young Lords.

The Black Panthers were infiltrated and violently dismantled – and a number of their members were murdered – specifically to destroy their mutual aid efforts, which included free food, education, child care, health care, and legal aid programs. The Black Panthers even offered sickle cell screening programs, and were so successful that they opened 13 free health clinics across the country.

These mutual aid programs were perceived as a threat to the U.S. government. In a 1969 memo, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover wrote that the Black Panthers’ Breakfast for Children Program “represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities [...] to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.”

We are being quite literal when we say that mutual aid, when practised by people of colour, has led to community members being targeted, incarcerated, and murdered by the government.

To try and undercut the Breakfast for Children Program’s success, the U.S. Department of Agriculture launched a breakfast pilot program in 1966, giving free meals to children whose families were below the poverty line – but without the radical political education the Panthers’ program provided. Former Black Panther Norma Amour Mtume said in an interview, “I really do believe that the government [expanded] their program because of the work we were doing.”

The Black Panthers were committed to a decolonial and anti-capitalist lifeway, and their efforts were systematically destroyed by the federal government. We are being quite literal when we say that mutual aid, when practised by people of colour, has led to community members being targeted, incarcerated, and murdered by the government. It is imperative for those who are practising mutual aid to know these histories.

Co-option is violence

When Black and Indigenous people work to end their communities’ dependency on the settler state through community care, they threaten the foundations of settler colonialism and capitalism. Above all else, settler colonialism and capitalism require our complacency in the face of continued theft of land, mass incarceration, and exploitation of labour in order to extract resources and build empires of profit.

Mutual aid is a unifying term, putting a name to the practices that many of us BIPOC folx have been acting on all our lives. We, as organizers of colour, will not allow white organizers, non-profits, and philanthropists to co-opt our teachings in a time of panic. By practising mutual aid, we are making a long-term commitment to the upheaval of white supremacy. Mutual aid demands that white people and settlers relinquish control in order to contribute at all.

Mutual aid is Indigenous lifeways and sovereignty; it is Black thrivance and power. Both will outlive anarcho-communist theory and non-profit co-option.

Mutual aid was not born out of survival – its initial purpose was to help our communities thrive. Yes, it has been used in times of crisis to help the most targeted in our society survive, but that is not enough. We must be committed to seeing people thrive, not just scrape by.

Mutual aid is Indigenous lifeways and sovereignty; it is Black thrivance and power. Both will outlive anarcho-communist theory and non-profit co-option. It is not simply a theory, but a practice which many people of colour have been acting on, and which predates colonialism and capitalism. This is important to note, because the co-option of mutual aid without accountability is racism.