Plain language summary (What is this?)

- People often assume that disabled people can only get their needs met by institutions like long-term care facilities, government programs, or charities.

- But we can often meet our needs in a better, faster, and safer way outside of institutions, by using support from our communities. The article explores four successful cases of people doing this.

- The Disability Justice Network of Ontario is an organization in Hamilton that’s collected donations of mobility and medical equipment that disabled people can borrow, like crutches, walkers, and glucose monitors.

- Chorus is the name of a big apartment building near Vancouver, built to give people with intellectual disabilities independent apartments. They live alongside families and elders. Disabled people who need it get a little staff support to live there. It is affordable for everyone who lives there.

- StopGap is an organization begun in Toronto that builds one-step ramps, mostly through volunteers, to make buildings wheelchair accessible.

- Carly Boyce, who lives in Toronto, offers workshops and a zine on ways to support suicidal friends without calling the police or going to a mental hospital.

Government programs, non-profit organizations, and institutions often fail to meet disabled peoples’ needs, especially undocumented migrants or those who haven’t been formally labelled as disabled. People frequently assume that disabled people can only get their needs met by institutions like long-term care facilities, hospitals, and clinics. But we can often meet our needs more directly outside of institutions through networks of care and mutual aid. This article explores four case studies of successful care for disabled people provided in the community.

DJNO’s Assistive Devices Library

Michael Hampson, an activist in Hamilton, Ontario, needed repairs to his power wheelchair. Ontario’s Assistive Devices Program helps people with long-term physical disabilities pay for equipment, but the OADP didn’t cover the repairs that Hampson so frequently needed and which he couldn’t afford on his own. In 2020, he died after a long period of deteriorating health, worsened by a consistent lack of mobility.

Sahra Soudi hears such stories far too often: disabled community members in need of usable assistive devices but unable to access them because of cracks in government programs. Fed up with the state’s negligence, Soudi and the rest of the team at the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, a disabled-led organization based in Hamilton, have taken action.

In December 2021, the team began gathering donations of assistive devices, including manual wheelchairs, ankle boots, crutches, walkers, mobility and white canes, and glucose monitors and test strips. Four months later, they opened an assistive devices library in Hamilton. The library works much like any other: locals email the library to submit a request for equipment, and if it’s available, they go pick it up. They can keep their equipment loan for up to six weeks, or longer if they renew it, and must return it in good condition once they no longer need it.

The DJNO team has received a huge amount of support, with community members across the country calling for their cities to implement similar projects. The library has not only provided disabled people with the tools they need in their day-to-day, but also highlighted how they aren’t getting their basic needs met by Ontario’s Assistive Device Program. It shows that by sharing resources among neighbours, we can meet each other’s needs without the red tape, wait times, and means testing of programs run by the state.

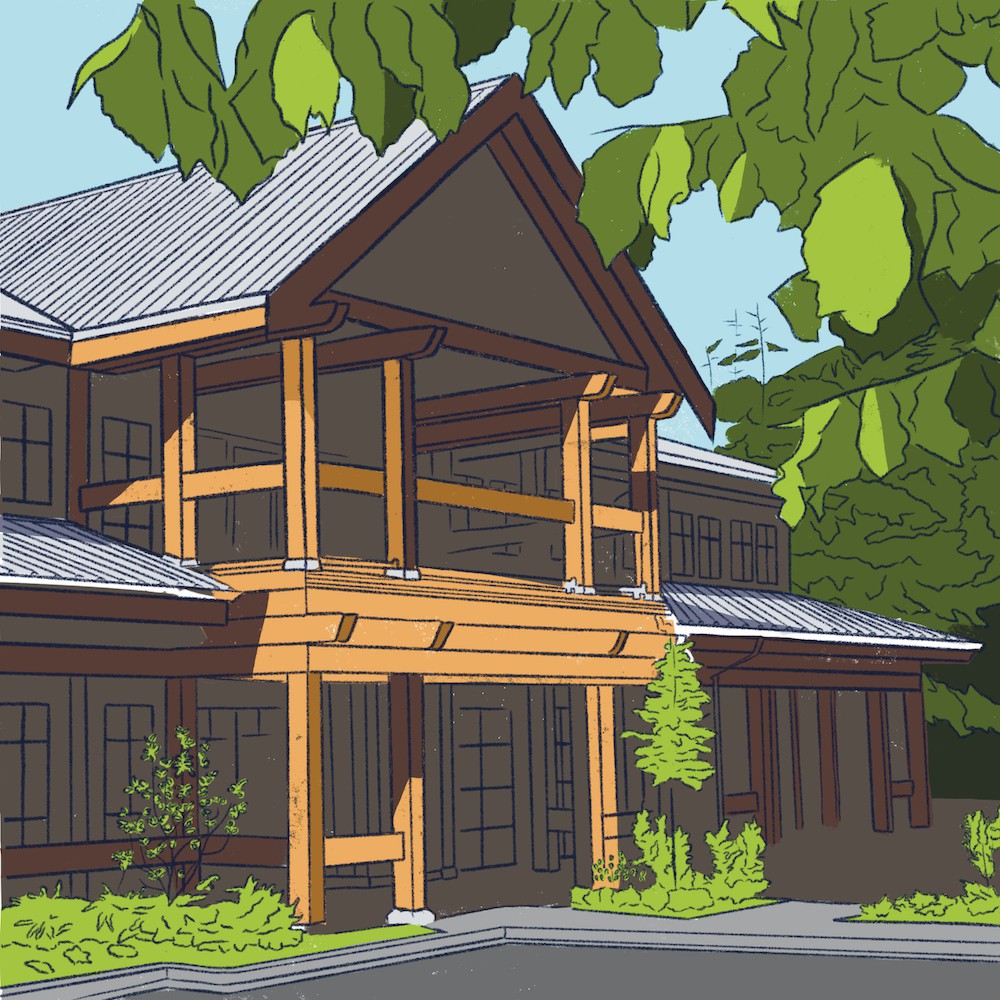

Chorus integrated housing

Accessible affordable housing is scarce in B.C. The province’s housing allowance for a single disabled person is just $375 per month, while the greater Vancouver area’s average one-bedroom monthly rent is $2,450. With soaring rents and limited coverage of home care services and prescription drugs, many disabled people are forced to live in long-term care facilities or institutions for people labelled with intellectual/developmental disabilities, even though disabled communities overwhelmingly call for deinstitutionalization and at-home care instead. The lack of housing options for disabled people is what prompted the creation of Chorus in 2016, an inclusive, below-market-rent 71-unit apartment building in Surrey. It includes 20 units for people with developmental/intellectual disabilities and 51 units for the general public, with rent ranging from $725 per month for a studio up to $1,375 for a three-bedroom unit.

Three non-profit organizations partnering under the name UNITI contributed to Chorus: Semiahmoo House Society (SHS) provides support for disabled tenants’ daily home activities; Peninsula Estates Housing Society (PEHS) owns and operates the building; and The Semiahmoo Foundation (TSF), a fund for developing housing options for disabled adults, invested in the development and holds the mortgage. Support workers from SHS check on tenants as needed and help with managing groceries, cooking, cleaning, budgeting, and other tasks.

Though three non-profits run the building, future tenants and their families were heavily involved in the planning and design. Back in 2004, SHS held interviews with disabled future tenants and their families about their desires for their homes. This was the first step in a lengthy consultation and planning process to ensure Chorus would work for its tenants. Once the design was complete, disabled tenants also chose their units before their non-disabled neighbours. Residents praise Chorus’s model for its support, affordability, and autonomy. Chorus’s success has prompted UNITI to pursue additional funding for more builds.

StopGap

After Luke Anderson acquired a spinal cord injury and became a motorized wheelchair user, many stores and cafés in his home of Toronto became inaccessible to him because of a single step outside of building entrances. Frustrated, he and some friends built a ramp using donated supplies, and a store owner agreed to put it at his shop’s entry. Made of wood, fitted with rope handles, brightly painted with a non-slip finish, and portable, with this ramp design shop owners don’t need the permit that the City of Toronto, like many other cities, requires for permanent ramps. Since beginning the project in 2011, over 2,000 more ramps have been built across Canada and internationally, using the one-step model Anderson and his friends came up with, and StopGap chapters have been created across the continent.

Since the summer of 2022, the team at StopGap has begun an accessibility census in Toronto, tracking how many ramps exist across the city and pinpointing locations that could use a StopGap ramp and don’t have one. While Ontario’s Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act mandates the province be barrier-free by 2025, there are few provisions for business owners to enable this physical access, and a 2019 review found that Ontario was nowhere near realizing the goal of the Act. As Anderson notes in an interview with Broadview, “in most municipalities, encroachment bylaws prevent ramps from living on the boulevard. We have this really ambitious goal of becoming a barrier-free province, but unfortunately there are these antiquated policies in most municipalities across Canada that are restrictive and prevent equal access.” So, he and other members of StopGap explain the relative ease of setting up removable ramps and educate adults and children to reduce barriers as much as possible.

Carly Boyce’s suicide prevention training

Since Grade 7, Carly Boyce has been supporting friends contemplating suicide. She’s attended a number of suicide intervention trainings, but many formalized trainings weren’t discussing the systems and structures causing suicidal ideation among Boyce and her friends.

“I’ve seen people who were really scared for their own safety [being] told by doctors or other formal systems that they were fine, or were dismissed as ‘attention seeking,’” Boyce tells Briarpatch. “I’ve also seen people who were struggling but also managing okay with peer support and their own systems of care be held against their will, and while in psych wards, be infantilized, have their gender and/or sexuality be pathologized, be given meds or other treatments they don’t find useful. It seemed like nearly everyone I knew was either getting not enough help, too much help, or help that didn’t actually help!”

So, in 2016, she created Suicide Intervention (for Weirdos, Freaks, and Queers), a peer education workshop designed as a safer space. Attendees can talk about ways of supporting their friends through suicidal ideation without using institutions they may have had harmful experiences with, like police, emergency rooms, and psychiatric wards. She has also transformed her workshop into a zine in order to make these tools more easily accessible and shareable.

Unlike some more formalized trainings, Boyce acknowledges in the zine that there’s “no secret recipe, no magic spell that will guarantee that all the people you love who struggle with suicide will stick around.” The trainings are a space to gain tools and be in community with others who are doing related work to move away from default crisis responses that rely on police and incarceration. “The more I understand the interconnectedness of various struggles, the less alone I feel in the work, which has made it much more joyful and sustainable for me,” Boyce explains.

She believes that gathering to discuss suicide is in itself a radical act: “folks who believe in autonomy and compassion and gentleness and resisting state intervention and incarceration […] we are powerful,” she writes. “We are willing to break a pervasive silence around suicide.”