“There is no historical study of the Sixties Scoop in print,” Métis scholar Allyson Stevenson explains in the opening chapter of her recent book, Intimate Integration.

While there have been books that deal more generally with Indigenous child welfare, personal accounts by Indigenous adoptees and survivors, and academic articles or papers on the subject, until now there hasn’t been a book focusing on the history of the ’60s Scoop in Canada. The term refers to the abrupt increase in that decade of the number of interventions by Canadian social workers who apprehended Indigenous children to be placed in foster care or adoptive homes. More specifically, Stevenson’s book centres on Saskatchewan government policy and its use of adoption as a tool of Indigenous elimination. The book also provides a brief overview (and lengthy bibliography) of the existing writing on the ’60s Scoop and Indigenous child welfare. The last chapter details the emergence of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in the United States in 1978 and its impact on Indigenous social movements and organizations in Canada.

Stevenson points out in the first chapter of her book that despite public apologies in recent years from provincial governments and political parties, the ’60s Scoop hasn’t had the same high profile in Canadian politics as residential schools.

Two documentary films on adoptees and reconnection are mentioned in the book’s notes: A Place Between (2007) and Red Road: The Barry Hambly Story (2004). In Stevenson’s words in the main text of her book, “these personal accounts reveal the human component missing in academic publications.” However, there are other important films – such as Birth Of A Family (2017), Foster Child (1987), and Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986) – that could have been mentioned or discussed as well, given that they are just as powerful and freely accessible on the National Film Board’s website.

Stevenson points out in the first chapter of her book that despite public apologies in recent years from provincial governments and political parties, the ’60s Scoop hasn’t had the same high profile in Canadian politics as residential schools. While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC’s) first four calls to action deal with child apprehension and child welfare, there has been no public commission on the ’60s Scoop, and a Métis and non-status Indians class action lawsuit remains unresolved.

An adoptee herself, Stevenson describes Saskatchewan, the province in which she was born and raised, as “the heart of Canada’s colonial enterprise,” the place where Indigenous elimination has been “rendered most violently.” This is a claim some readers might find surprising, given that Indigenous struggles in other provinces have taken the bulk of the media spotlight in recent years. Stevenson says her work is meant in part to remedy gaps in public knowledge. As she points out, Patrick Johnston, credited with coining the term “’60s Scoop” in his 1983 book Native Children and the Child Welfare System, wrote to the Saskatchewan government that same year, saying that the problems and barriers to constructive change in child welfare were “most acute in Saskatchewan.”

An adoptee herself, Stevenson describes Saskatchewan, the province in which she was born and raised, as “the heart of Canada’s colonial enterprise,” the place where Indigenous elimination has been “rendered most violently.”

Non-Native or non-Saskatchewan-based readers may be surprised to learn from Intimate Integration of the involvement of the New Democratic Party (NDP) and its forerunner, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), in coercive Métis community relocation, Indigenous child apprehension, and the advertising program known as Adopt Indian and Métis (AIM). In 2019, the Saskatchewan NDP, although not in power at that moment, even joined other parties in making a public apology for its share of the responsibility for “all the lives that were harmed by the Sixties Scoop.”

Yet Stevenson’s book is far from just another recounting of tragedy, as it is also a history of Indigenous resistance, particularly Indigenous women’s resistance to the removal and assimilation policies of successive Saskatchewan governments, both conservative and social democratic, over several decades. Stevenson places her work within a wider framework of the Cree and Métis concept and practice of kinship, wâhkôhtowin, which is not limited to human familial relations but involves an expansive understanding of relationality in general.

Long before colonizers weaponized adoption against us, it was an Indigenous practice, and much of Stevenson’s book deals with the ways in which patriarchal Canadian law and policy interfered with this, fracturing the Indigenous extended family structure in an attempt to impose the Western nuclear family in its stead. This process took place through the patriarchal regulation of status and residency through the Indian Act, as well as through residential schools, the experimental removal of Métis communities and children for so-called “rehabilitation,” and, increasingly during and after the ’60s, child apprehension to foster care or adoption.

When Indigenous families sought to adopt Native children, they were often stymied, and legal adoption didn’t convey status to the child under the Indian Act. Amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 allowed provincial laws to apply to reserves, which had previously been exclusively federal jurisdiction, and this change increased the rate of child apprehension.

Long before colonizers weaponized adoption against us, it was an Indigenous practice, and much of Stevenson’s book deals with the ways in which patriarchal Canadian law and policy interfered with this, fracturing the Indigenous extended family structure in an attempt to impose the Western nuclear family in its stead.

As a Métis and Cree person myself, raised separately and disconnected from my Indigenous family from Treaty 6 territory in Saskatchewan, I’ve long been personally interested in understanding the dynamics of colonial removal and attempted assimilation, but also Indigenous resistance and reconnection. While grasping that government legislation and policy enforce colonialism directly, I’ve also been interested in – and, to some extent, have personally experienced – how white citizens take up the logic of elimination themselves, often without even fully understanding what they’re doing.

Canadians tend to view colonial institutions in isolation from each other, as temporary structures that have been and continue to be dismantled along the road to reconciliation, rather than as replaceable parts of an overarching and ongoing system. They also tend not to see themselves as active agents of colonialism who sustain it through mundane daily activities, instead viewing themselves as mere bystanders living in the wake of a completed historical project.

Their focus on residential schools allows Canadians to place colonialism securely in the past, to characterize Indigenous people as merely traumatized individuals in need of personal healing rather than as members of families, communities, and nations in need of both system-wide social change and land, water, and kinship restoration for collective repair and growth.

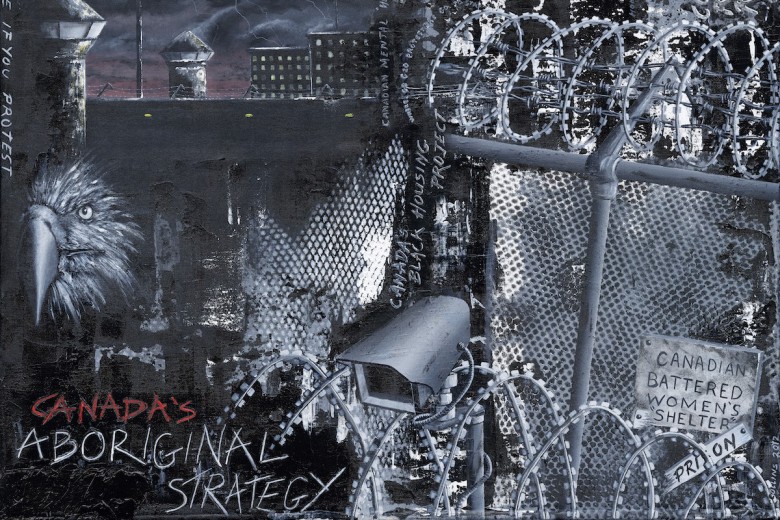

Meanwhile, the massively disproportionate rate of Indigenous children taken into care, the federal government’s continuous legal battle against equitable funding for Indigenous child welfare, and the recent struggle of Indigenous prisoners and their family members on the Prairies against prison conditions under COVID-19 have all marked the continuity between past and present colonial institutions.

The critical conditions of Indigenous child welfare are not limited to Saskatchewan. According to a 2020 report by British Columbia’s Representative for Children and Youth, “Indigenous children account for less than 10 per cent of B.C. children, but represent 66 per cent of those in care.”

While grasping that government legislation and policy enforce colonialism directly, I’ve also been interested in – and, to some extent, have personally experienced – how white citizens take up the logic of elimination themselves, often without even fully understanding what they’re doing.

Stevenson’s book, given its focus on the ’60s Scoop, only incidentally deals with the institutions of the criminal justice system. It will be left to other written works to expand upon Intimate Integration in order to specifically situate prisons and policing as colonial institutions that stand in dynamic relation to child apprehension and the colonial child welfare system. Perhaps we will see something akin to what Robyn Maynard’s book Policing Black Lives accomplished with its overarching look at various institutions in the carceral continuum, from border regulation to child welfare.

In her notes, Stevenson mentions that in 2018, Canada finally announced the development of Indigenous child welfare legislation. An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families (Bill C-92) became law on January 1, 2020, but how it’s to be applied is still a matter of discussion and development. The law’s wording around collective Indigenous rights and its lack of detail regarding federal funding leave it still somewhat weaker than what is found in the ICWA in the United States, despite 41 years having passed between them.

Meanwhile, Canada faces its 10th non-compliance order from the federal Human Rights Tribunal regarding equitable funding for Indigenous child welfare, continues to fight against the broad application of Jordan’s Principle, and has announced that the tribunal’s orders for equitable funding won’t apply to Indigenous governments who take on responsibility for child welfare through Bill C-92. Cindy Blackstock, head of the First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada, recently pointed out that this stipulation wasn’t divulged to some First Nations governments before they signed on.

Canada’s current divestment of financial responsibility reflects one of the ways that the state has historically benefited from adoption instead of foster care, as expressed by government officials during the ’60s Scoop and detailed in Stevenson’s book. Private families would take over both the financial cost and direct implementation of assimilation from the state.

Stevenson’s book, like her PhD dissertation on which it’s based, challenges the typical view of the state as a public sphere that is clearly separate from the private realm, which it is meant to respect and protect. When it comes to us, as Indigenous Peoples, the state knows no boundaries or barriers except the ones we can throw up ourselves, on the ground, and through challenges in the courts.