The Democratic Socialists of America Canada Twitter account first appeared online in September 2019. The account began to tweet regularly – somewhat earnestly, somewhat in jest. Soon, other accounts with names like 1917DSACANADA, DSA Canada – Build, and DSA Canada Distributism Caucus popped up, joining in with tweets like: “So excited to build a new Canada with our allies at @CanadaDsa! We believe the economy should support entrepreneurs, skilled craftsmen [sic] bartering their trade, family farms, mom-&-pop shops, & worker owned cooperatives with the spiritual guidance and support of the Catholic Church.” Reactions ranged from bemused (clever political satire!) to jokingly skeptical (the original account was surely a psy-op!)

It was, indeed, all just a joke. Andrew Neville, who lives in Halifax and co-produces the podcast Dog Island – “Atlantic Canada’s #1 cultural marxist podcast” – started the initial account, inspired by a poster advertising a DSA meeting in Toronto. “In my head, the phrase ‘Democratic Socialists of America Canada’ was the funniest thing I could think of at the time,” he says. Neville’s increasingly irreverent tweets and the tangle of interactions with the mystery caucus accounts quickly attracted hundreds of followers.

“In my head, the phrase ‘Democratic Socialists of America Canada’ was the funniest thing I could think of at the time.”

“There’s enough Canadians phone banking for [the Bernie Sanders campaign] right now that a Toronto chapter of the DSA is [not] outside the realm of possibility in any way,” Neville says. A number of Twitter users even messaged the DSA Canada account asking how they could get involved and whether there were upcoming meetings scheduled.

“It does speak to people wanting to be involved in something like [the DSA]. I think there is something to be said about feeling part of a massive network of support and solidarity […] and that’s what people who were responding sincerely to the joke were obviously hungry for,” Neville reasons.

Eventually, Twitter shut down the DSA Canada account – in response, Neville suspects, to a tweet encouraging DSA members (Americans) to travel to Canada and vote in the 2019 federal election. (Another joke.) The various other caucus accounts – which initially tweeted in faux outrage about censorship of DSA Canada – “This would never happen on a democratically controlled platform like tiktok” – eventually sputtered out.

The idea of a Democratic Socialists of America in Canada stuck around. Just months later, in January, a new set of DSA-inspired accounts appeared online, with the name Democratic Socialists of Canada (DSC). Dropping the “A” was a signal that this time, the accounts were “real.” Or, at the very least, they were serious. The new DSC accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter deployed a logo nearly identical to the one Neville created, and immediately began to push hundreds of posts, some sponsored, and a handful of meet-up events in cities across the country. The posts all had the slick, uniform styling of a carefully managed brand. And the brand worked. Even the earliest posts attracted dozens of comments and shares.

Despite this traction, the accounts went mostly unnoticed by online leftists in Canada until Myka Conners published a short but scathing expose about Joe Roberts, one of the main figures behind the group. Conners’s investigation points to Roberts’s professional history of working for Zionist non-profits and comments on the hollow vision of democratic socialism outlined on the DSC’s website – which includes absurdities like: “In many ways, Canada is already the first post-nationalist country in the world.”

Branding is easier than base building. And building an activist brand, if that’s what the DSC is, entails creating the impression of a base through likes, comments, and clicks.

Ultimately, Conners deems the DSC “nothing more than a vanity project of a professional managerial class fundraising consultant,” and Roberts “a grifter looking for your donations. He is not your comrade.”

That an account named “Democratic Socialists of Canada” has attracted as many followers as it has – over 6,000 on its Facebook page – is not all that much of a surprise. Branding is easier than base building. And building an activist brand, if that’s what the DSC is, entails creating the impression of a base through likes, comments, and clicks. Name recognition, a uniform and familiar style, frequent posts, and an active page administrator who responded to comments was all the DSC needed to establish an online presence. (Someone from the DSC even responded to a thread on Reddit’s CanadaLeft.)

Like the savviest of 21st-century marketing experts, Roberts and the founders of the DSC saw a problem and wanted to turn it into an opportunity. “The feeling is in the air that people are fed up with the NDP and the Liberals,” Conners says. “And [Roberts] sees this – he does feel like a tech disruptor, this person who has an idea about how the market works and wants to come in and get credit for reinventing the wheel.”

What the opportunity is – that is, what the democratic socialist vision the DSC planned to organize for – is less clear. The group’s online presence is an ahistorical jumble of platitudes and memes that reference big-ticket policy questions and news stories – pharmacare, public ownership of utilities, income inequality – with messaging straight from the Bernie Sanders campaign’s playbook. But the DSC’s posts often fall short of Sanders’s incisive moral clarity, landing somewhere in the Pete Buttigieg word salad realm: “In the fight for a fairer & more equitable Canada, the politics of empathy will win. We all do better when we care about the outcomes for each other.”

The disconnect between the DSC’s breezy digital socialism and the violent realities of organizing within and against a settler-colonial state is perhaps no better illustrated than by a meme that the page posted amid the arrests of Wet’suwet’en land defenders resisting the Coastal GasLink pipeline that reads: “Why don’t we all benefit from Oil & Gas? Shouldn’t the people own what’s in the ground? Shouldn’t it benefit our society instead of an elite few?”

But the DSC’s posts often fall short of Sanders’s incisive moral clarity, landing somewhere in the Pete Buttigieg word salad realm: “In the fight for a fairer & more equitable Canada, the politics of empathy will win. We all do better when we care about the outcomes for each other.”

The DSC page administrators have since hidden a comment that the Vancouver Industrial Workers of the World’s Facebook page left on this post pointing out the DSC’s hypocrisy in arguing for the nationalization of the oil industry while Indigenous activists blockaded railways to oppose colonial land theft.

The DSC wants socialism to be easy, new, now. “Dear 1%, we fell asleep for a while,” another meme reads. “We’re woke now. Sincerely, the Democratic Socialists of Canada.” In an email to me, Joe Roberts tells me that the DSC wants their movement to be “a big tent that brings people together looking for a better way forward” and that the group rejects “rigid dogmatism and litmus tests for membership as they limit what we can achieve together and exclude many of the people who are most in need of the reforms that DSC members are fighting for.”

To Conners, Neville, and perhaps the thousands of social media users compelled to like both the spoof DSA Canada and the DSC accounts, there seems to be no question that socialist organizing in Canada has fallen asleep, in desperate need of a reboot. The DSC isn’t it.

Building movements, not brands

If not the DSC, then who are Canada’s socialists? It’s a seemingly perennial question, one that has long stumped the media punditry, stoked political infighting, and prompted socialist splintering in electoral and activist circles alike.

Socialist political organizing took off in Canada following the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 and was fuelled by the Great Depression, which led to the founding of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). The Regina Manifesto, the CCF’s founding platform, elaborated a 14-point vision for a socialist Canada that outlined a set of interlocking political goals, from public ownership to children’s allowances.

“No CCF Government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Cooperative Commonwealth,” the manifesto promises.

The CCF folded in 1961, merging with the Canadian Labour Congress to give birth to the New Democratic Party, led by Tommy Douglas. Abandoning the CCF’s vision of a planned economy as the utopian pipe dream of a pre-war past, the NDP opted for a democratic socialist framework that could popularize the vision of full employment, a welfare state, and a mixed economy.

“No CCF Government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Cooperative Commonwealth,” the manifesto promises.

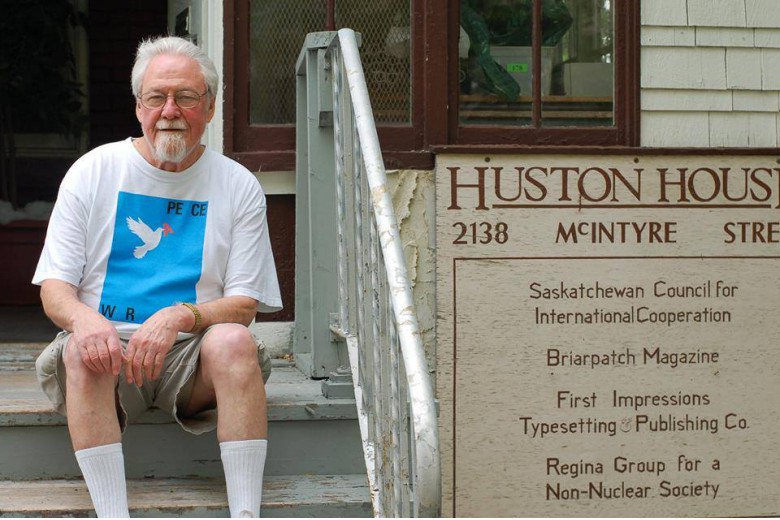

Under Douglas, the NDP affiliated with the Socialist International – “a worldwide organisation of social democratic, socialist, and labour parties,” per their website – and adopted a broad program that successfully pushed the government to enact key policies like medicare and the Canada Pension Plan. But the party’s strategy and principles remained distinct from those of the CCF. As Mel Watkins, an architect of the Waffle who recently passed away on April 2, 2020, puts it: “the CCF as social movement [became] the NDP as party.”

As the party’s leadership professionalized over the ensuing decades and the NDP’s platform meandered from democratic socialism to social democracy, the eradication of capitalism once energetically imagined by the CCF receded further in the rearview mirror of history.

Movements vying to reignite the socialist flame in the NDP’s platform are as old as the party itself. The Waffle, led by Watkins, James Laxer, and his father Robert Laxer, began in 1969 as a resolution to be introduced at the NDP’s federal convention in Winnipeg. Although the resolution itself failed, “the Waffle happened much more than expected,” says Watkins. “We were too strong to simply disband but too weak to win.”

The Waffle went on to form a short-lived party, the Movement for an Independent Socialist Canada, and inspired a slew of future such attempts: the Campaign for an Activist Party’s fight for the Ontario NDP; the Left Caucus; the Socialist Caucus; Socialist Alternative; the New Politics Initiative, which initially called for a full disbanding of the NDP; the Leap Manifesto; and the Courage coalition, among others.

Movements vying to reignite the socialist flame in the NDP’s platform are as old as the party itself.

Each faction has used distinct tactics: some have lived and died by the party, others have broken from party confines to form independent organizations, while others still, like the Courage coalition, work within and without, targeting the NDP in coalition with social movements and activists. Their general consensus is that the activist left can – and should – harness the NDP’s infrastructure.

Whether any of this has worked depends on how one defines success. The persistent dissatisfaction with the NDP on the left implies that activists haven’t yet landed on a winning strategy. The NDP overwhelmingly voted to remove the word “socialism” from the party’s constitution in 2013. (There was an unsuccessful attempt to reintroduce it in 2018.) The party’s third way drift toward the centre has continued steadily, and despite leadership rejigs and the election of insurgent MPs, the party appears largely impervious to activists’ efforts to push the party to the left. Recently, the Ontario NDP voted for a bill that conflates criticism of Israel with antisemitism, despite vocal popular opposition and coordinated organizing by a coalition including Independent Jewish Voices Canada, the Courage coalition, and Palestine House.

If the NDP cannot – or will not – be changed, for many this means the party must be abandoned altogether. “The 17 years I spent in the NDP proved to be a waste of time,” says Stuart Parker, former leader of the Green Party in British Columbia, who quit the B.C. NDP in 2018 after the party announced billions of dollars in subsidies and tax breaks for LNG Canada, paving the way for Royal Dutch Shell and the Coastal GasLink pipeline. “Of course, what we’re seeing right now in Wet’suwet’en territory is the same thing that we see always when Shell shows up: part of the deal of bringing in Shell is that your police force turns into their brute squad,” Parker says.

In March, the Georgia Straight revealed that two weeks before B.C. NDP Premier John Horgan insisted that the government had “no authority” over the RCMP’s invasion of Wet’suwet’en land, B.C. NDP solicitor general Mike Farnworth wrote a letter authorizing “the internal redeployment of resources” for the RCMP to enforce Coastal GasLink’s injunction.

After quitting the NDP, Parker and a group of activists went on to form the B.C. Ecosocialists, a provincial political party that Parker hopes will serve as “a vehicle that the next generation of activists can use.” The party, alongside the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, has called for Farnworth’s resignation following the Straight’s investigation.

“The 17 years I spent in the NDP proved to be a waste of time,” says Stuart Parker, former leader of the Green Party in British Columbia, who quit the B.C. NDP in 2018 after the party announced billions of dollars in subsidies and tax breaks for LNG Canada.

The party’s founding policy platform runs 33 pages and includes proposals for a Green New Deal – with sections on public finance, forestry, the creation of a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples’ Equity, plans for arts and culture, and more. (It is notable, though, that the word “socialism” does not appear once, outside of the party’s name, nor do the words “Indigenous sovereignty.”)

The B.C. Ecosocialists’ initial strategy, Parker says, is to shut down the province’s LNG projects. The party’s first line of attack will be to target the balance of power at the legislature – currently just one vote. “If there’s anything we can do to touch the conscience of one of those 43 people, then we have the opportunity to negotiate,” Parker says.

In the next election, the B.C. Ecosocialists hope to run a full slate of candidates. In many ridings, their aim will simply be to force the NDP’s hand: after denying the NDP the margin of victory, the B.C. Ecosocialist candidate will offer to stand down in return for a recant on the province’s LNG projects. “We are trying to build a vehicle that properly serves social movements that are being built and have been built,” Parker asserts. “Our purpose is to give voice to people who are already speaking out.”

Social movements, Indigenous activists, and community organizers, then, are setting the socialist agenda – outside of the electoral realm.

“When you get involved with party politics and electoralism, so much of your time and effort gets sucked into these protracted conversations that get you really far from issues that impact people on a daily basis,” says Paige Gorsak, an organizer with Climate Justice Edmonton who ran for the federal NDP nomination in Edmonton Strathcona in 2018. Electoral politics can be a “tool” for “bigger conversations,” says Gorsak, who ran for the nomination to inject climate issues into the political discourse. Gorsak also says that her run “pulled” a lot of people into Climate Justice Edmonton’s campaigns that the group hadn’t accessed before.

But party politics are also a barrier, explain Gorsak and Juan Vargas, who are organizing with the group’s Free Transit Edmonton campaign. Mention you’re with the NDP while canvassing and you might get a door slammed in your face. Community campaigns around “essential public services” like free and expanded transit, a key plank of a Green New Deal, says Vargas, can build bases of power at the local level to shift discursive and political needles on key issues without needing to refract issues through the fraught lens of electoral politics.

Social movements, Indigenous activists, and community organizers, then, are setting the socialist agenda – outside of the electoral realm.

Socialist organizing – whether by name or in principle – abounds. “There’s no question that the coincidence of extreme wealth concentration and the climate event is producing a set of material and cultural conditions that are making socialism happen, or at least making socialist movements happen,” explains Parker.

Curious, then, that many such movements and projects eschew explicitly socialist branding in favour of tightly focused issue-based campaigns like Millennium for All, a campaign challenging new security measures at the city’s library, which espouses a socialist vision without relying too heavily on the word “socialism.”

Thanks in large part to Bernie Sanders’ run for the U.S. presidency, socialism is trending. But if, as Alan Sears argues, four decades of the neoliberal narrative have all but eradicated the communities and practitioners fluent in traditional socialist vernaculars, and if the socialist vocabulary was “flawed and partial” to begin with, then perhaps the task for today’s socialists is not to revive an archaic language, or even a brand, but to recode the socialist political vision in new “living languages” intelligible to wider audiences. (See campaigns like People Over Profit Winnipeg, a group running a slate of eco-socialist candidates in the city's upcoming municipal election.)

The question that seems to preoccupy people – who are Canada’s true socialists? – therefore needs a rephrasing. Better ones might be: how are today’s socialists organizing? What does socialist success look like? What are their tools, strategies, tactics, and languages? How are socialist movements fighting for Indigenous sovereignty, land back, and decolonization?

After all, answering such questions – not creating another vacuous, rose-embossed branding campaign – is the work of movement building.

Update, April 27, 2020: In print, this article stated that People Over Profit eschewed explicitly socialist branding; the article has been updated to reflect that People Over Profit does explicitly use the word "socialism."