Content warning: graphic description of police brutality

On May 17, 2018, Calgary Police surrounded a home in Penbrooke Meadows. Two people – a man and a woman – unknown to the owners, had barricaded themselves inside the empty basement suite. After an hour-long stakeout, police entered the home. When they came out, the man was critically injured, and the woman was dead. For nearly a month the dead woman’s name was not released. It was the third fatal shooting by Calgary Police Service (CPS) officers that year.

Her name was Josephine Shelly Lynn Pelletier. She was Cree and Saulteaux, and she was 33 years old.

Growing up

Josephine – her friends called her Jojo – was born on February 25, 1985, in Regina, the third of five children. Her mother, Donna, struggled with drug addiction. She tells me over the phone that Josephine “barely knew” her father, a violent alcoholic who was in and out of jail for most of Josephine’s life. “She did struggle,” Donna says. “There was sexual assault. There was everything.”

Court records and Josephine’s testimony confirm a traumatic childhood. At a 2011 hearing where she was deemed a long-term offender – only the second woman in Saskatchewan to be declared as such – the court was told that Josephine was sexually abused by the brother of her stepfather, starting when she was three years old. He was never charged and the abuse continued until Josephine was 11.

Donna’s own childhood was filled with violence. “We were abused,” she says about the years between ages three and about 10, when she and her nine siblings were removed from their Regina home and sent to live with their grandparents on Muskowekwan reserve, outside of Regina, Saskatchewan. “It wasn’t until my older sister was 17 that she got us put back with our mom,” Donna recalls.

Josephine told the courts that the first time she got drunk, she was nine. By 13 she was using cocaine and shooting up with her stepfather. She first came into contact with social services when she was 11. “She used to run away from me,” Donna says, adding that her daughter spent time in foster care as a preteen, although “she ran from there, too.” Donna says Josephine was only in one foster home. Her court records indicate she was in “many foster homes” from “around age 11.” It is clear that no effort was ever made by the courts to establish the chronology of Josephine’s life, until that chronology included a list of crimes that meant she could be locked up for an extended period.

“She did struggle,” Donna says. “There was sexual assault. There was everything.”

Her education ended in sixth grade. It is heartbreaking and infuriating to think that a 12-year-old girl could quit school and no one – not a parent, not a teacher, not a social worker – was there to catch her as she fell. She joined a Regina street gang the following year and started doing sex work, in part to support her growing addiction to cocaine. At 19, she would be convicted of “communicating for the purposes of prostitution” after she approached an undercover officer whose job was to lie in wait for women like her.

Josephine’s first contact with state authorities outside of social services came when she was 12. Although court records say she was 13, she was born in February 1985 and the same records indicate her arrest was in May 1997. It’s another discrepancy in the legal documents that record her life. Names and facts – her mother’s first name, her age, the towns and cities where she was raised – shift like sand from one trial to the next, the fine details of her life all treated with less care and attention than the meticulous accounting of her Criminal Code violations.

That year she pushed and kicked a girl while stealing her basketball jersey. In the media the incident would be described as her “first violent crime,” one that would be among the evidence used in her long-term offender hearing. The courts used this incident, and three others – a fight with two other preteens, a fight with her mother, and a time she broke into a house and stole CDs and a stereo – as evidence she was dangerous enough to the public that it warranted up to 10 years of surveillance following her release.

Names and facts – her mother’s first name, her age, the towns and cities where she was raised – shift like sand from one trial to the next

A forensic psychologist who examined her prior to her long-term offender hearing reported that he saw “no obvious signs of psychotic illness or organic brain syndrome,” though she “likely qualified” for PTSD and an “alcohol related neurodevelopment disorder.” He noted that while incarcerated, she was prescribed Chlorpromazine – an antipsychotic medication used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

It is unsurprising to learn that Josephine was medicated with antipsychotics despite not being diagnosed as psychotic. A 2014 CBC investigation found that 62 per cent of female inmates in Canadian prisons were medicated with powerful antipsychotics. As an unnamed inmate told the CBC, “the medication seemed to be a trend to control behaviour. It seems far easier to give a prescription than help someone address past trauma.”

Donna says Josephine’s son, Isaac,* has been given “some kind of medication” while in prison, and she notices side effects. “Some days he talks,” she says. “And some days he’s very quiet.”

A disproportionate punishment

There is pride in Donna’s voice when she talks about Josephine’s decision to leave gang life behind. “She was no gang member. She got out.”

Donna also tells me that her daughter had begun connecting with her Cree and Saulteaux roots in the years following her long-term offender designation. “She sang powwow, she did sweats. She always smudged. She believed in that,” Donna explains.

Although Josephine told the courts that many of her familial relationships – including with her mother – were “problematic,” Donna says her daughter maintained the bonds of family. “She always phoned,” Donna says. “She loved her nephews and her nieces, and her cousin. They took each other as brother and sister.” She was especially close to her older sister, Sherry, who died in December 2014 after contracting a post-surgical infection. At the time, Josephine was incarcerated in Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ontario, and was not permitted to attend the funeral in Regina.

Josephine was especially worried about her son, Isaac, who was born when she was 15. He spent part of his childhood in foster care, where his grandmother tells me he was “whipped and beaten.” After that, he lived with Donna. Isaac is currently imprisoned in Calgary, awaiting trial on charges stemming from the events on the day his mother was shot. “She wanted to raise her son,” Donna explains. But she struggled. “She was good to talk to, but sometimes she was angry.”

“She loved her nephews and her nieces, and her cousin. They took each other as brother and sister.”

For Indigenous women, anger is likely to be pathologized and punished rather than understood and managed. From Josephine’s first violent crime – the push that left her victim with “slight bruising and a sore jaw” – to her adolescent conviction for spitting at hospital staff while being restrained in a psychiatric unit, the courts repeatedly made the decision to criminally prosecute acts that, while technically crimes, were really acts of childish aggression and the desperation of the powerless.

This is not to say Josephine didn’t hurt others – she twice robbed people while threatening them with a knife, causing one victim “significant psychological harm.” In 2003 she stabbed a woman who “she mistook for someone else.” As a whole, though, her punishments have been wildly disproportionate to her acts, and they have not been, as the courts assert, efforts to “rehabilitate” her.

“There’s no help there,” Donna says of the jails. She says when Josephine advocated for herself as an incarcerated Indigenous woman, her requests for support went unanswered. “She wanted to take these [culture-based rehabilitation] programs and [corrections officials] wouldn’t allow her.”

The justice system withholds treatment programs it claims incarceration is meant to provide, as punishment – thrusting inmates into a vicious cycle where the programming they need to prevent reoffending is withheld when they reoffend.

Indigenous advocate Naomi Sayers, from Garden River First Nation, tells me Canada’s prison system is a fresh iteration of residential schools. “The schools took away many from our communities. Now it is the prison system.” The judge who ruled Josephine was a long-term offender said a long period of imprisonment was the only way to provide her with “meaningful assistance” in terms of “counselling,” “therapy,” “life skills,” and “vocational training” – but Sayers says it was too little, too late. “If she received that kind of support before being sentenced, I can only imagine she might still be here.”

“If she received that kind of support before being sentenced, I can only imagine she might still be here.”

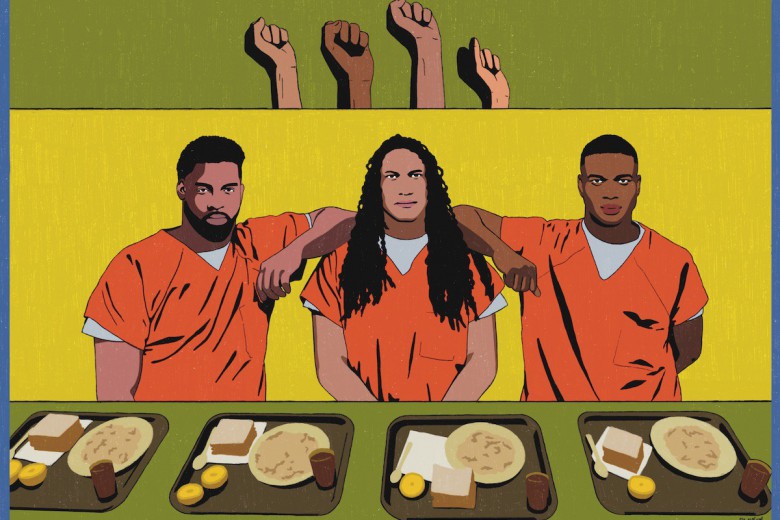

More than half of Josephine’s life was spent under government supervision, and between the ages of 13 and 30, she spent fewer than three years outside of correctional institutions. According to a 2015 APTN profile, during this time she spent a full year being held in solitary confinement – allowed out of her cell for only an hour a day, shackled and chained, her mouth covered by a spit hood.

In March 2016 she was released to a women’s supervision unit in Toronto, but October 2016 found her back in court for a “breach.” She had violated parole by using cocaine. Her lawyer argued this was not a crime, but something “inevitable,” to be expected in the lifelong process of addiction recovery.

The trial for her breach was presided over by Canada’s “poet judge” – Justice Shaun Nakatsuru, who has a reputation for lyrical, compassionate rulings. Nakatsuru acknowledged that the years and miles between Josephine and her community had taken a toll. She wanted to go home, and Nakatsuru – who observed that jail had “not been very useful” in rehabilitating Josephine – agreed to return her to Saskatchewan, though she was later transferred to a halfway house in Calgary that had treatment programs considered more suitable for her.

The ruling was regarded as a step forward in the delivery of justice to Indigenous offenders, with Ottawa law firm McElroy Law calling it “humanizing” and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association’s Rights Watch blog calling it “a breakthrough in access to justice.”

But Sayers notes that the praise came from settlers, who have a misguided belief that settler courts can deliver justice to Indigenous people. “The irony is that Justice Nakatsuru said he was sending her home but when she returned home, it was the state that killed her.” She says rulings like Nakatsuru’s make the state-sponsored erasure of Indigenous peoples from their lands “more palatable.”

“The irony is that Justice Nakatsuru said he was sending her home but when she returned home, it was the state that killed her.”

It is chilling to think that the Canadian government – with its history of strategic starvations, forced relocations, and cultural and literal genocide of Indigenous peoples – has the power to give or withhold something as fundamental as “home.”

This gets to the heart of why there can be no reforming the Canadian justice system. Even when it is operating at its most benevolent, it functions as a means of controlling the lives of Indigenous people, providing the state with a new pass system, allowing it to regulate the movements of First Nations people by invoking a Criminal Code they never consented to. “If you are very good – and very lucky,” the justice system says, “perhaps you will get to go home.”

Deadly force

One might argue that if Josephine Pelletier did not want her life controlled by the government, she should not have committed crimes. “You have free will,” Nakatsuru wrote to her in his 2016 ruling. But it rarely is as simple as “choosing” a life of crime.

Some of her crimes – like when she violated her parole by using cocaine – harmed no one but herself, but still elicited punishment from the state. Incarceration itself is a kind of violence that builds upon the trauma of the past – prisons are disproportionately filled with people who inherited or have lived through colonialism, poverty, forced displacement, and abuse. It is impossible to know what Josephine’s life might have been like if she had not been burdened with trauma – some of which she had to shoulder before she was even born, and some of which was inflicted by the prison system itself.

We don’t know why Josephine left the Calgary halfway house where she had stayed since 2016, nor do we know what she did in the days leading up to May 17, 2018 – though Donna speculates that she “must have got some drugs.” We do know that mid-morning that day she and her son, Isaac, broke into the basement suite of a bi-level home.

The owners returned to find the basement door open and called police. The Canine Unit surrounded the home before calling in the more heavily armed tactical team. Josephine was barricaded in a room and according to police, she had a knife.

Incarceration itself is a kind of violence that builds upon the trauma of the past.

On May 16, 2017 – a year prior to the day before Josephine was killed – Calgary Police ordered an independent review of use of force by the service, with the reviewer expressing hope that it would be “useful in [CPS’] efforts to improve its practices in respect of use of force.” The final report was released a month before Josephine was shot dead.

It recorded 21 police shootings by CPS officers between 2012 and 2017, leaving eight dead. It recommended “an enhanced focus on de-escalation,” while noting that “de-escalation can be perceived as contrary to the traditional role of the law enforcement officer as it appears to force police officers to pause and reflect” on use-of-force guidelines. CPS has killed two people since the report was released in April 2018, one of whom was Josephine; the other – 25-year-old Jaskamal (Jas) Singh Lail – was having a mental health crisis.

Police and Josephine’s family have offered differing accounts of what happened May 17, 2018. What is agreed upon is that in the minutes before the shooting, police gained entry to the suite and fired on Isaac with rubber bullets, and he was taken from the house with a punctured lung. Then two officers opened fire on Josephine, shooting her dead.

According to Donna, who tells me the police are “lying” about details they’ve provided, Isaac opened the door to let officers in. She says it was the injuries caused by the cops’ ARWEN “less lethal” Launcher – so called because the rubber bullets it fires are not intended to kill, though it can be deadly at close range – that sent the teen to hospital. She told me that she saw seven wounds on her daughter’s body, indicating that Josephine had been shot multiple times. This was confirmed to APTN by a family friend in June. Neither Donna nor Briarpatch have been able to obtain Josephine’s autopsy report, because her death is the subject of an active investigation by the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team.

The story told by CPS is that Isaac forcibly confined Josephine in the room, then Josephine stabbed Isaac while he was forcibly confining her. Police entered the premises when they heard “sounds of distress” and fired rubber bullets at Isaac, who the police say had already been critically injured by his mother. After that, two officers opened fire on Josephine, who they say was still being forcibly held.

She told me that she saw seven wounds on her daughter’s body, indicating that Josephine had been shot multiple times.

It’s quite a story. In fact, as Calgary Police Association president Les Kaminski told the Calgary Star, “It’s straight from the _Twilight Zone._” Nevertheless, Kaminski was impressed with how the situation was handled. “[The officers] saved someone’s life.” It’s not clear who he’s talking about – the homeowners, who were already safely away from the scene? Isaac, who was allegedly forcibly confining Josephine when she was killed, and still ended up in the hospital?

In 2017, Kaminski was charged with assault with a weapon and perjury after he allegedly threw a man “like a rag doll, face first” onto the hood of a car and struck him twice on the back of the neck with a baton during a 2008 traffic stop in downtown Calgary. Kaminski had been elected head of the police union just two months prior to when charges were laid, and the charges were later dropped.

The systems are not broken. Police brutality and mass incarceration of Indigenous people show a colonial justice system functioning as it’s meant to. Colonial justice says that Indigenous people are meant to be dead or confined. There is no justice within the system – there is no justice until the system is dismantled.

Josephine was buried with her eagle feather, next to her sister Sherry. Her son could not attend the funeral because he was in a Calgary jail awaiting trial for his alleged confinement of his mother. Donna says prosecutors told him he’ll get three years if he pleads guilty – more if he goes to trial. Donna doesn’t believe Josephine stabbed him, or that he confined Josephine. “She was paranoid” when she was high. “She would lock herself up, stick a knife in the door [to keep it shut].”

Donna says the investigation into Josephine’s shooting will take a year – the file was passed to Alberta’s Serious Incident Response Team – and in the meantime, she will wait, and worry about her grandson.

And if he is very good – and very lucky – perhaps they will let him go home.

*Name has been changed. Isaac* is not a minor, but he is a teenager, and his name is not on the public record. Briarpatch did not speak with him to get his permission to use his real name, and we have chosen to use a pseudonym.

_1200_675_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)