In 2015, several Indigenous women began reporting forced and coerced sterilizations in Saskatoon hospitals. The history of forced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada is long – just in the early 1970s at least 1,200 Indigenous people were sterilized as a measure to reduce Indigenous populations and lessen the state’s treaty responsibilities. Seeking justice, Senator Dr. Yvonne Boyer and Dr. Judith Bartlett interviewed the women about their experiences and authored a report that included calls to action for the Saskatoon Health Region.

But incarcerated people would not have been able to participate in the review process Drs. Boyer and Bartlett oversaw in 2017 to gather testimony. So in 2019, the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies (CAEFS) began a new project to engage with people currently incarcerated in federal women’s prisons to discuss reproductive health, autonomy, oppression, and justice. CAEFS is an organization working towards a world without prisons; part of this work includes providing advocacy for women, trans, and non-binary people experiencing incarceration in federal prisons designated for women across the country.

The incarceration of Indigenous women is a recognized continuation of colonial, genocidal processes such as the residential schools and the ’60s Scoop.

CAEFS sought to expand the discussion beyond sterilization, to broadly encompass reproductive justice. The term reproductive justice was developed by Black American feminists 25 years ago, expanding concepts of reproductive rights beyond a focus on abortion to include the right to self-governance over one’s body, to not have children, to choose to have children, and to parent those children in safe and sustainable communities.

Putting people in prison impedes reproductive health and justice by limiting health care access and destroying family connections. In Canada, this is especially true for Indigenous people who are incarcerated. As of January 2020, 42 per cent of federally incarcerated women were Indigenous – more than eight times the percentage of Indigenous women in Canada’s total population. Despite talk of “reconciliation,” the population of federally incarcerated Indigenous women increased by 60.7 per cent over the past 10 years. And you can draw a direct link between overincarceration of Indigenous women and over-representation of Indigenous children in foster care, as many of the women in prison were once in state care: today, it is estimated that there are 14,970 Indigenous children in state care. The incarceration of Indigenous women is a recognized continuation of colonial, genocidal processes such as the residential schools and the ’60s Scoop.

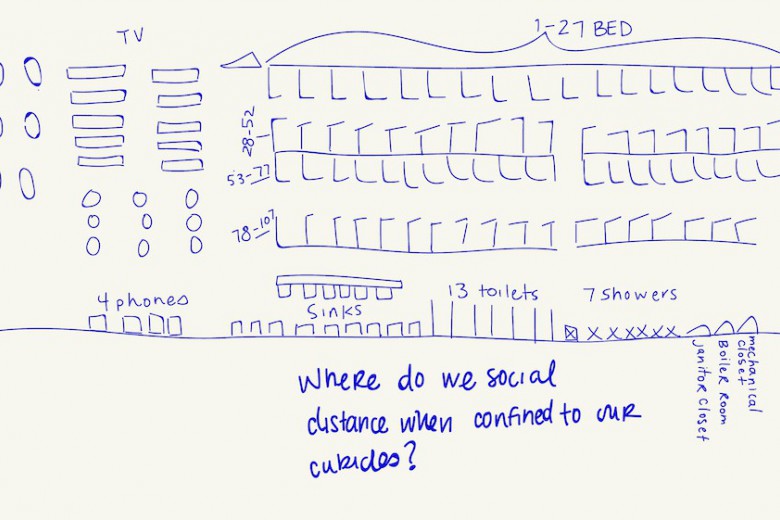

Prisons are dangerous places. They threaten health and safety, including reproductive health and safety. People in federal prisons experience higher rates of mental illness, and pre-existing mental illness is the most significant risk factor for mental illness associated with reproduction. Health is the most common topic of complaints from people in federal prisons. Access to sexual and reproductive health information is severely restricted from people experiencing incarceration as they have no access to the internet and limited access to health promotion programs and education.

Prisons are dangerous places. They threaten health and safety, including reproductive health and safety.

The reproductive justice workshop materials were created through a partnership between Martha Paynter, an independent registered nurse and one of the authors of this article; lawyers, CAEFS staff; and Indigenous Elders; and with approval of senior Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) representatives. The workshops were conducted from October 2019 to January 2020, with approximately 200 people who were incarcerated in five of the six federal prisons for women. Discussion during the workshops converged around five main themes: 1) Sexual assault and consent; 2) Reproductive control of Indigenous people; 3) Prison and separation from children; 4) Prison and reproductive health; and 5) Prisons and violations of bodily autonomy. From these themes we developed recommendations for advocacy.

In this article, we summarize some of what we heard from workshop participants, using direct quotes to let them speak in their own words.

Sexual assault and consent

Sexual trauma is a significant determinant of young women’s criminalization. Prison is a site for further trauma. As one participant said, it is “More trauma, more trauma, more trauma. What is the point of being told to work on yourself when there just keeps being more trauma?” Some participants discussed how experiences of sexual and physical abuse led to their criminalization, because they “had had enough” and reacted violently against victimization: “Women in prison can be victim, victim, victim to abuse their whole life and then they finally react. She finally says ‘Enough.’ And now she’s in jail.” Several participants talked about how criminalization intersects with risk of sexual assault and that women with experience of criminalization or sex work are less likely to be believed: “I’m a drug dealer, I party, I’m a drug user, I’ve been to prison – who is going to believe me if I call the cops?”

Reproductive control of Indigenous people

The workshop content included an overview of the colonial history of reproductive oppression of Indigenous communities. Elders provided invaluable teachings and support during the workshops. All participants were familiar with, and many had experienced, the current overrepresentation of Indigenous children in foster care: “Some of the homes that they put these children in are worse [than the poverty or neglect they are being removed from]. I am against Family Services. I’ll always be against them. I was in foster care. It was gross and disgusting.”

Participants spoke to the intergenerational impact of child removal: “I was raised by grandparents who went to residential schools. My mom was affected, she couldn’t raise me right. I was affected.” The murders and disappearances of Indigenous women in Canada forced the dislocation of a family and community: “My mom died when I was a child and I was in [dozens] of different foster homes.” The participants felt the over-incarceration of Indigenous people began in the youth criminal justice system and had an impact on generations after: “You could say prisons are the new residential school.”

“My sister was at the hospital, she had a C-section for her twins, and they were holding up her hand to the paper, to consent to sterilization.”

In several of the federal institutions we were asked to explain sterilization and the issue of forced sterilization. Many were familiar, however: “My sister was at the hospital, she had a C-section for her twins, and they were holding up her hand to the paper, to consent to sterilization.” Another explained, “I had six kids. My son was one month old. I always told my grandma I was going to have nine kids. My doctor convinced me [to get my tubes tied].” For one participant, sterilization happened in the context of criminalization: “When I got arrested, I got my tubes clamped.” The inability to get pregnant now was affecting their relationships, such as for one participant who said, “The guy I’m with now wants me to have it reversed but that costs a lot of money.” One participant considered how health care providers could participate in this type of coercion: “I wonder how the nurses felt, I wonder what they would say if we asked them? How would they even start with decolonization?”

Separation from children

Almost all incarcerated parents are separated from their children. The arrest of a parent is traumatic for children: “I’ve seen women bawling their eyes out, because their kids don’t know they’ve been arrested, they were at daycare.” Some were terrified of how their children were coping without them, “My kid has never been away from me.” One woman said the separation from her children and barriers to seeing her children had caused her to lose hope. Others thought by pleading guilty they would at least have certainty about where they would be incarcerated, only to be disappointed by the outcome: “I pled out, to be here, to have stability so my kids could visit me here. I’m supposed to get visits twice a week. I haven’t seen my kids.” Several participants described how they lost access to their children as punishment for “behaviours” inside the prison, including mental illness: “If you get a dirty urine you get your visits suspended.” One participant said federal incarceration prevents mothers from being able to address family court matters: “If you have a family court date, you are not brought to your court date [from jail/prison]. People won’t even know [of the date].”

“I wouldn’t even be here if they hadn’t taken my kids away. If they had helped me with my addictions. I wouldn’t have lost hope. They don’t give you a chance.”

Struggling with the provincial departments of Child Protection Services emerged as a dominant concern in the participants’ lives. “I don’t think they recognize how much it disrupts the family to take the mother out of the home.” Participants described the removal of their children as often abrupt, and perceived to be without any preventative measures: “Child and Family Services – it’s supposed to be the last resort, but taking your kids is the first thing they do. Take your kids and leave you to the wolves.” One participant described how the removal of her children launched the spiral that resulted in her criminalization: “I wouldn’t even be here if they hadn’t taken my kids away. If they had helped me with my addictions. I wouldn’t have lost hope. They don’t give you a chance.” Participants also spoke about being fearful of calling the police when they experience domestic abuse because of the chance of their children being removed by Child Protection Services.

Parents in the workshops described minimal supports while incarcerated: “There is a program, you can read aloud a book, have it recorded and sent to your kid.” Even where programs are offered, people held in maximum security do not have access to them: “Not all people get out of max, to medium or minimum where they can take these programs.” Some felt there needed to be more pragmatic support to prepare people for release so they could succeed as parents: “Rebuilding relationships. The hardest part for women is people taking a chance on them.” They had practical ideas, such as “a list of places that will employ you with a criminal record.”

“I pled out, to be here, to have stability so my kids could visit me here. I’m supposed to get visits twice a week. I haven’t seen my kids.”

In every workshop, we discussed the federal Institutional Mother-Child Program that allows eligible mothers to have their children with them full or part-time in the institution. The presence of the children in the prisons was welcomed: “It grounds me to have babies around.” However, many of the women could not participate because of the strict eligibility criteria, limited space, and delays to receive approval. They felt it was unfair that some women got to participate and others not: “We all have babies and want to be with them.”

Prison and reproductive health

Although the workshops took place in federal prisons, many of the participants described what it was like to be pregnant while in provincial facilities. One participant said when she went into labour in a provincial facility, no one believed her. Several described being placed in solitary confinement or restraints while pregnant: “When I was pregnant, I was handcuffed and shackled and I fell going up the stairs.” Canada does not have specific legislation or policy in place to prohibit the practice. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act does not speak to unique provisions for pregnancy and delivery, nor does the Correctional Services Canada Commissioner’s Directive 800 governing health.

As some participants pointed out, it is not possible to have reproductive health when you are physically and/or emotionally unwell; reproductive health is part of the whole body, and the whole body faces threats to health while inside federal prisons. Participants described significant restrictions on access to health services. The prisons lacked drug and alcohol addictions counsellors and spiritual care. Several participants said their health concerns were ignored. Some felt it was invasive to have correctional officers present in their medical appointments.

Violations of bodily autonomy

Participants described experiencing verbal and physical violence that violated their bodily autonomy. “Anyone who’s been in the jail system has seen someone be abused. That’s a normal part of jail.” Lack of public understanding of what happens inside was a problem: “I don’t think the public know people are tossed into provincial seg [solitary confinement] naked.”

Participants spoke about the degradation they felt having their movements under surveillance and control in the federal institutions: “I can’t go to the bathroom unless they open my door.” The participants also described being policed in their physical relationships with other women while incarcerated. As one woman said, “I’m not free to just be a person. How they treat people in here… someone is going to kill themselves.” Several participants described homophobic comments and threats they experienced from correctional officers.

“When you say you feel suicidal, they put you in seg, they strip you down, put you in a babydoll [a smock], you get no water, no mattress. You are reaching out for help and that’s what you get.”

The CAEFS Reproductive Justice workshops were held around the time that federal changes to administrative segregation and “structured intervention units” (SIUs) were being implemented. The participants expressed skepticism about whether there would be real changes. “They just give you more hours outside of your cell. But what are you supposed to do? Walk back and forth?” They described the experience as dehumanizing: a woman in segregation was taken out for a walk, “Like a dog.”

The participants said that institutional response to expressions of suicidal ideation was punishment: “When you say you feel suicidal, they put you in seg, they strip you down, put you in a babydoll [a smock], you get no water, no mattress. You are reaching out for help and that’s what you get.” The experience was bleak: “I got a whole lot of nothing, I was dry celled [held in solitary confinement without access to a toilet].” One described the effect of segregation as, “You are eating bitterness.”

Calls for advocacy

From the discussions during the workshops, the facilitation team developed several priority areas for change that can be adopted by CAEFS, CSC, and the legal and health professions, including:

- CAEFS should advocate for the adoption of United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the Mandela Rules, to bring health and health services to the forefront of federal legislation and policies governing corrections.

- CAEFS should advocate for an end to personal (strip) searching.

- CAEFS should support reproductive justice, informed consent and sexual health education for people experiencing criminalization.

- CAEFS should augment work to advance non-carceral supportive housing options for incarcerated parents to live with their children in community.

- CAEFS should expand its reach to enhance engagement with women, girls, and trans and nonbinary people incarcerated in provincial facilities and advocate for arms-length investigator roles, similar to the federal Officer of the Correctional Investigator, in every province and territory.

- CSC should adhere to stipulations in the Mandela Rules. CSC should ensure people in prison have physical copies of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Mandela Rules, the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and of the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls. These documents support women to understand their rights and to self-advocate.

- CSC should improve transparency and communication regarding the federal institutional Mother Child Program.

- CSC must provide people in prison with timely information, access to legal representation and transportation to family court proceedings.

- The legal profession should consider the impact of incarceration of mothers and parents on children. The Best Interest of the Child should be a routine consideration in presentence reports and parole hearing decisions. Counsel should raise gender-based considerations for sentencing and parole, such as parenting responsibilities and early childhood need for bonding with the primary parent.

- Health professionals must understand their responsibilities under their professional codes of conduct and the Mandela Rules for the compassionate, comprehensive, and confidential health care of people experiencing criminalization.

- The federal Office of the Correctional Investigator should highlight reproductive health and parenting indicators in its annual reports.

CAEFS has accepted the recommendations of the report and is integrating reproductive health as a focus of its advocacy work in federal prisons designated for women. Prison abolition is, for CAEFS, a critical path to reproductive justice.

You can read the full CAEFS report, Reproductive (In)justice in Canadian Federal Prisons for Women, here.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)